From David Ruccio One of the arguments I made in my piece on “Class and Trumponomics” (serialized on this blog—here, here, here, and here—and recently published as a single article in the Real-World Economics Review [pdf]) is that, in the United States, the class dynamic underlying the growing gap between the top 1 percent and everyone else was the much-less-remarked-upon divergence in the capital and wage shares of national income. Thus, I concluded, “the so-called recovery, just like the thirty or so years before it, has meant a revival of the share of income going to capital, while the wage share has continued to decline.” Well, as it turns out, that conclusion is more general, characterizing not just the United States but much of global capitalism. We know that—not just in the United States, but in a wide variety of national economics—the share of income going to the top 1 percent has been rising for decades now. Thanks to the work of Peter Chen, Loukas Karabarbounis, and Brent Neiman (and the full paper [pdf]), we also know that corporate profits (across some 60 countries) have also been rising. We document a pervasive shift in the composition of saving away from the household sector and toward the corporate sector. Global corporate saving has risen from below 10 percent of global GDP around 1980 to nearly 15 percent in the 2010s.

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

One of the arguments I made in my piece on “Class and Trumponomics” (serialized on this blog—here, here, here, and here—and recently published as a single article in the Real-World Economics Review [pdf]) is that, in the United States, the class dynamic underlying the growing gap between the top 1 percent and everyone else was the much-less-remarked-upon divergence in the capital and wage shares of national income. Thus, I concluded, “the so-called recovery, just like the thirty or so years before it, has meant a revival of the share of income going to capital, while the wage share has continued to decline.”

Well, as it turns out, that conclusion is more general, characterizing not just the United States but much of global capitalism.

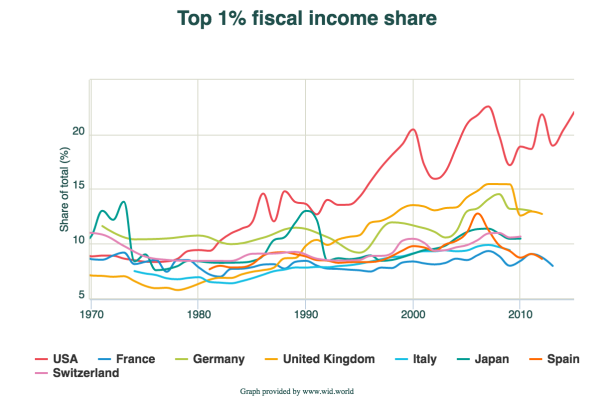

We know that—not just in the United States, but in a wide variety of national economics—the share of income going to the top 1 percent has been rising for decades now.

Thanks to the work of Peter Chen, Loukas Karabarbounis, and Brent Neiman (and the full paper [pdf]), we also know that corporate profits (across some 60 countries) have also been rising.

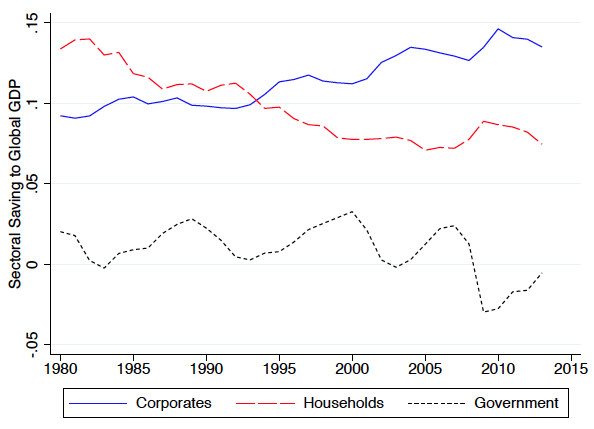

We document a pervasive shift in the composition of saving away from the household sector and toward the corporate sector. Global corporate saving has risen from below 10 percent of global GDP around 1980 to nearly 15 percent in the 2010s. This increase took place in most industries and in the large majority of countries, including all of the 10 largest economies.

According to their analysis, the rise of corporate saving mirrors an increase in undistributed corporate profits, corresponding to a decline in the labor share for the global economy.

Moreover, the increase in corporate saving exceeded that in corporate investment, which implies that the corporate sector improved its net lending position. Just as I concluded in the case of the United States, the improved net lending position of corporations is associated with an accumulation of cash, repayment of debt, and increasing equity buybacks net of issuance.

If you put the two trends together—increased individual income inequality and increased corporate savings—what we’re witnessing then is increasing private control over the social surplus. Wealthy individuals and large corporations are able to capture and decide on their own what to do with the surplus, with all the social ramifications associated with their decisions to invest where and when they want—or not to invest, and thus to accumulate cash, repay debt, and repurchase their own equity shares.

And proposals to decrease tax rates for wealthy individuals and corporations will only increase that private control.

Why is it anyone would want to save such an economic system?