From David Ruccio Forget Bitcoin. It’s the underlying technology, blockchain, that is generating the most excitement. Even utopia! Bitcoin is a digital currency that was invented in 2009 by a person (or group) who called himself Satoshi Nakamoto. His stated goal was to create “a new electronic cash system” that was “completely decentralized with no server or central authority.” After cultivating the concept and technology, in 2011, Nakamoto turned over the source code and domains to others in the bitcoin community, and subsequently vanished. While Bitcoin (and other so-called cryptocurrencies, such as Ethereum, Ripple, and the other 1500 or so other such currencies) have generated a great deal of media attention (for their novelty, their ability to permit transactions beyond

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

Forget Bitcoin. It’s the underlying technology, blockchain, that is generating the most excitement. Even utopia!

Bitcoin is a digital currency that was invented in 2009 by a person (or group) who called himself Satoshi Nakamoto. His stated goal was to create “a new electronic cash system” that was “completely decentralized with no server or central authority.” After cultivating the concept and technology, in 2011, Nakamoto turned over the source code and domains to others in the bitcoin community, and subsequently vanished.

While Bitcoin (and other so-called cryptocurrencies, such as Ethereum, Ripple, and the other 1500 or so other such currencies) have generated a great deal of media attention (for their novelty, their ability to permit transactions beyond government surveillance and control, and their wild gyrations in price), it’s blockchain, the technology behind Bitcoin, that carries the utopian promise of remaking the economy and society.

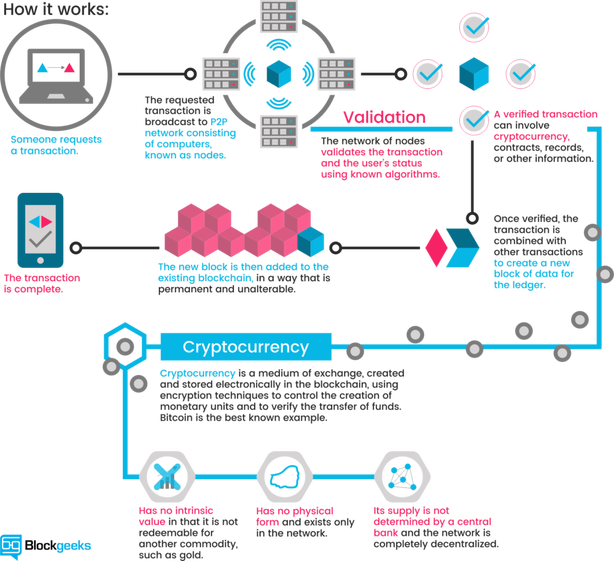

At its most basic, blockchain provides a decentralized database, or “distributed digital ledger,” of transactions that everyone on the network can see. This network is essentially a chain of computers that must all approve an exchange before it can be verified and recorded.* The technology can work for almost every type of transaction involving exchange-value, including money, goods, and property. It can also serve as the basis for a variety of other functions, from distributed cloud storage and the recording of property titles to authenticated voting and decentralized social media platforms.

For some (such as Brendan Markey-Towler), blockchain technology makes it possible not only to envision, but to establish a viable pathway toward, a utopian alternative to contemporary society.

On the face of it a mundane and boring technology for bookkeeping, blockchain is actually revolutionary because it makes the anarchist utopia a more realisable dream than has ever before been possible. At the very least it provides the strongest challenge ever posed to the monopoly of the state over the promulgation, formation, keeping and verification of institutions and the public record. The purpose of this essay is to investigate the conditions under which this might occur, and the dynamics of a society organised using blockchain technologies.

According to Markey-Towler, blockchain can serve as the basis for organizing an anarchist utopia—”a society which is composed of groups formed entirely by mutual association and absent violence and coercion.” The idea is that the keeping of verifiable records via blockchain technology allows for the creation of a public record that is kept by everyone and updated by collective consent, which means there is no nexus of power (such as the state or monopoly corporations) that can be exercised to corrupt or use the public record as a tool of extortion.** Even more, the existence of blockchain technology makes it possible to exit from existing economic and social relations and to practice, if only in a selected domain, a different way of organizing economic and social transactions. Thus, it permits a “sort of competition” for adherents between the two systems—one organized in and by the state, the other via decentralized distributed ledgers—and creates the possibility for individuals to choose the set of institutions associated with the alternative, blockchain technology.

I have no interest here in exploring either the feasibility or desirability of such a blockchain utopia (although I have elsewhere, e.g., here and here). My focus for the moment is otherwise—on the fact that the claims about blockchain from the latest example of a long series of “technological utopianisms.”

Many will remember this 2012 iPhone commercial claiming the device is the most used camera in the world. Light piano music twinkles and images of people living their best lives flit past. It is utopic desire, crystallized: the ad says that the gadget will make us happy, and that, through its lens, we’ll all evolve into a better version of ourselves. Facebook (like other social media) promised to give “people the power to share and make the world more open and connected.” And there’s Uber, which pledges “to make transportation safer and more accessible, helping people order food quickly and affordably, reducing congestion in cities by getting more people into fewer cars, and creating opportunities for people to work on their own terms.”

Many will recognize these as pledges that technology will usher in the new utopian society. But, as Howard P. Segal reminds us,

few if any of the high-tech zealots of our own day have even considered the possibility that, far from being original, their crusades fit squarely within a rich Western tradition of technological utopianism. It is not likely that very many of them realize how old-fashioned they really are when celebrating technology’s prospects for transforming the nation and, in due course, the world.***

They are merely the latest in a long line—starting with the late-sixteenth- and early-seventeenth-century Pansophists (such as Tomasso Campanella, Johann Valentin Andreae, and Francis Bacon) through the utopian socialists of the early nineteenth century (especially Henri de Saint-Simon) through the numerous technological utopians of the late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth centuries (including Edward Bellamy, Henry Olerich, Edgar Chambliss)—of prophets of progress and the possibility of achieving utopia through the introduction and expansion of new technologies.

Technological utopianism, as I am using it here, refers to one or more of the following three claims:

- Technology is the means for creating a perfect society.

- The perfect society itself is modeled on technology.

- The perfect society is one that promotes the development of new, better technologies.

Clearly, Markey-Towler’s enthusiastic claims for blockchain technology meets the definition. So, as it turns out, does contemporary mainstream economics.

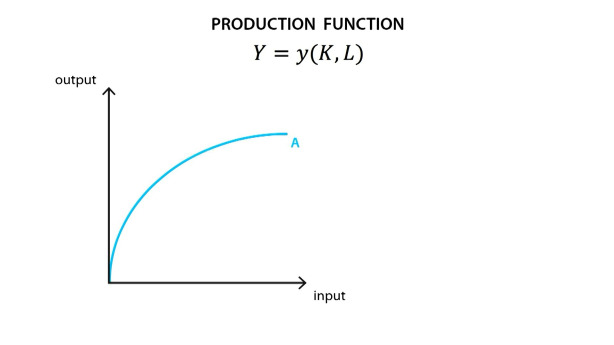

Mainstream economists treat technological innovation as the sine qua non of economic and social progress—the key to economic growth and the achievement of global prosperity. It is introduced in the production function as y, the “recipe,” whereby capital (K) and labor (L) can be combined to produce output (Y). Thus, even without changes in the amount of capital and labor, output will be increased as new technologies are introduced. Thus, when they move from an individual firm’s production function to economy-wide economic growth, mainstream economists claim that the key is the increase in productivity due to technological change, which is generally referred to as the “Solow residual” (named after Nobel laureate Robert Solow).****

The mainstream argument is that the level of production and the rate of economic growth can be increased by the introduction of new technologies, which lead to higher levels of productivity. More goods and services are thus made available to satisfy human wants, thus solving the problem of scarcity.*****

Moreover, mainstream economists claim, an economic system based on free markets is the best way of encouraging the development and application of new technologies. At a microeconomic level, profit-maximizing firms have an incentive choose the best, more efficient technologies, for themselves and for the economy as a whole. And free international trade is the best way of increasing the pool of research and development experiments, from which the best technology is chosen. Thus, technology trade increases national income in each country and raises the total gains from trade.

Contemporary mainstream economics thus combines market utopianism with technological utopianism.

As I see it, the biggest problem with technological utopianism is that it takes politics out of the equation—whether in imagining solutions to economic and social problems or envisioning the role of technology in a radically different kind of economy and society. Technology thus becomes a substitute for politics. As Aleszu Bajak has recently explained with respect to finding a solution to climate change,

Relying on a technological fix that’s just over the horizon avoids the mountain moving required to wean ourselves off fossil fuels, bring hundreds of countries into agreement on how to limit and clean up emissions, and alter the consumption habits of an entire civilization. Those are systemic complexities ingrained in our economies and cultures. Propping up glaciers to limit sea level rise, sprinkling iron dust into the oceans to encourage plankton growth to absorb carbon, or spraying the skies to reflect the sun’s heat just seems simpler.

Much the same can be said of obscene inequalities in the distribution of income and wealth, the “diseases of despair” that now afflict a large portion of the U.S. population, or the prospect that new forms of automation will eliminate jobs and make workers redundant. In each case, a technological fix is promised—tax-rate changes for inequality, the expansion of healthcare insurance for increasing levels of addiction, a universal basic income for labor-substituting robots—when the problem itself is political, not technical.

And that means the solution has to be political—organizing people to criticize the existing set of institutions, in order to imagine and create new ways of organizing the economy and society. New technologies may even have a role to play in enabling people to see such a “virtual reality.”

Tackling problems as deeply ingrained as the ones humanity faces right now will require facing a question that technology alone cannot address: are we willing to band together to criticize and change the existing set of economic and social institutions?

*To carry out a transaction a party needs two things: a wallet (public key) and a private key. A wallet is a string of digits and letters, also called a public key. It is an address that appears each time a transaction is done. The private key is a string of random digits that should be kept in secret. When someone enables a transaction it is signed with a private key, which is only visible to a sender. Then a network of nodes carries that transaction making sure that it is valid. Once it confirms its validity the transaction is put into a block where, because it has been “hashed,” it is virtually impossible to change without being detected.

**Technically, blockchain fulfills three requirements: (a) it guarantees a certain degree of reciprocity and security with respect to exchange and property; (b) it is sufficiently easy to interact with and to keep records; and (c) it permits a certain degree of freedom to use one’s property, that is, it is secure from theft, corruption, and manipulation.

***Howard P. Segal, Technology and Utopia (American Historical Association, 2006), p. 66.

****Solow (1957) started with a neoclassical production function where Yt = At•F(Kt, Lt), where Yt is aggregate output in time period t, Kt is the stock of physical capital, Lt is the labor force and At represents productivity growth due to technology. Solow then estimated the variables for the U.S. economy for the period 1909-49, where output per labor hour approximately doubled. According to his estimates, about one-eighth of the increment in labor productivity could be attributed to increased capital per person hour, and the remaining seven-eighths to the residual.

*****This is one of the reasons why Robert Gordon’s work on the slowing-down of U.S. productivity growth has been met with such concern.