From David Ruccio The goal of mainstream economists is to get everybody to work. As a result, they celebrate capitalism for creating full employment—and worry that capitalism will falter if not enough people are working. The utopian premise and promise of mainstream economic theory are that capitalism generates an efficient allocation of resources, including labor. Thus, underlying all mainstream economic models is a labor market characterized by full employment. Thus, for example, in a typical mainstream macroeconomic model, an equilibrium wage rate in the the labor market (Wf, in the lower left quadrant) is characterized by full employment (the supply of and demand for labor are equal, at Lf), which in turn generates a level of full-employment output (Yf, via the production

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

The goal of mainstream economists is to get everybody to work. As a result, they celebrate capitalism for creating full employment—and worry that capitalism will falter if not enough people are working.

The utopian premise and promise of mainstream economic theory are that capitalism generates an efficient allocation of resources, including labor. Thus, underlying all mainstream economic models is a labor market characterized by full employment.

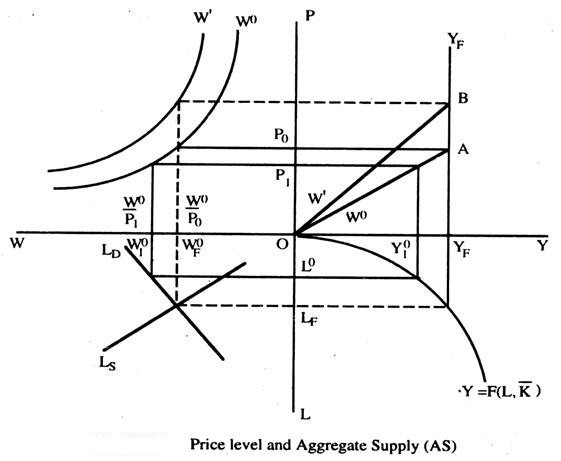

Thus, for example, in a typical mainstream macroeconomic model, an equilibrium wage rate in the the labor market (Wf, in the lower left quadrant) is characterized by full employment (the supply of and demand for labor are equal, at Lf), which in turn generates a level of full-employment output (Yf, via the production function, in the lower right quadrant) and a corresponding level of prices (P0, in the upper quadrants). If the money wage is flexible it is possible to ignore the top left quadrant, because, in that case, the equilibrium real wage, employment and output are Wf, Lf and Yf, respectively, whatever the price level. With flexible money wages, the aggregate supply curve is independent of the price level and is represented by YFYF.

That’s the neoclassical version of the story. The Keynesian alternative is that the aggregate supply curve is relatively elastic below full employment and the wage rate is fixed by institutions, and therefore is not perfectly flexible. In such a case, aggregate demand determines the level of output, which will normally fall below the full-employment level.

And so we have the longstanding argument between the two wings of mainstream economics—between the invisible hand of flexible wages and the visible hand of government spending. But, equally important, what the two theories of macroeconomics have in common is the ultimate goal: full employment. In other words, both groups of economists presume that the aim of capitalism is to generate full employment and that, with the appropriate policies—free markets for the neoclassicals, government intervention for the Keynesians—capitalism is capable of putting everyone to work.

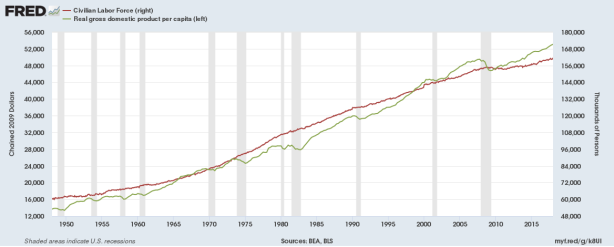

But the argument also goes in the opposite direction: capitalism works best when everyone is working. That’s because capitalist growth (e.g., in terms of Gross Domestic Product per capita, the green line in the chart, measured on the left) is predicated on the growth of the labor force (the the red line, measured on the right).

Mainstream economists also argue that a low work rate is an important cause of low incomes and high poverty. They argue that, when considering different policy interventions for this population—including improving educational attainment, raising the minimum wage, and increasing the number of two-earner families—the most beneficial intervention for improving incomes is to assume that all household heads work full-time.

Finally, mainstream economists argue that, in addition to increasing incomes and decreasing poverty, work has an additional benefit: it gives people dignity and a sense of self-worth. The idea, as articulated for example by Brad DeLong, is that having a job gives workers an honorable place in society, which presumably they are deprived of if they receive some kind of government assistance—whether in the form of payments from one or another anti-poverty program or a universal basic income. “Just giving people money” (according to Eduardo Porter) disrupts the incentive to work and undermines the “social, psychological, and economic anchor” associated with having a job.

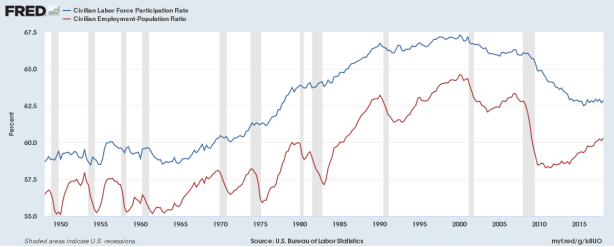

That’s why there’s such an intense debate these days over the participation rate of U.S. workers. Even though the unemployment rate has fallen to historically low levels (and now stands at 3.8 percent), the lack of participation—whether measured in terms of the labor force participation rate (the blue line in the chart) or the employment-population ratio (the red line)—remains much lower than it was a couple of decades ago.* According to mainstream economists, that’s why rates of growth in output and incomes have slowed. There simply aren’t enough people working.

Once again, there’s an ongoing discussion among mainstream economists about the causes of that decline and what to do about it. More conservative mainstream economists tend to focus on the supply side of the labor market and the unwillingness of workers to make themselves available—mostly because they’re benefiting from some part of the social safety net (such as disability insurance, welfare, or government health insurance). Liberal mainstream economists also worry about the supply side (especially, for example, when it comes to women, who might not be able to work because they don’t have adequate childcare) but put more emphasis on the demand side (for example, the elimination of specific kinds of jobs based on international trade, automation, or the effects of economic downturns). Underlying this debate is a shared presumption that more people working will be better for them and for the economy as a whole.

Even portions of the Left accept the idea that the goal is to move toward more work. Thus, for example, both modern monetary theorists and Bernie Sanders argue in favor of a government job guarantee. The idea is that, if private employers can’t or won’t make the decisions to hire workers and create full employment, then the government needs to step in, as the “employer of last resort.” Again, the presumption—shared with those in both wings of mainstream economics—is that the goal of the current economic system and appropriate economic policy is get more workers to work more.

The utopianism of full employment is so entrenched, as a seemingly uncontested common sense, it’s difficult to imagine a different utopian horizon. But there is one, which emerges from at least three different theoretical and political traditions.

In the Marxian tradition, more work also means more surplus labor, which benefits all those who manage to get a cut of the surplus—but not workers themselves, who fall increasingly behind their employers and others in the small group at the top. That’s because, as employment increases, more workers are performing both necessary and surplus labor. Therefore, even assuming the rate of surplus extraction remains constant, the total amount of surplus created by workers increases. But, of course, the rate itself often increases—for example, as a result of competition among capitalists, who find ways of increasing productivity, which tends to lower the amount they have to pay to hire their workers (as I explain in more detail here). So, what appears to be an unalloyed good in the mainstream tradition—more jobs and more workers—is an economic and social disaster from a Marxian perspective. More workers produce more surplus, which is used to create a growing gap between those at the top and everyone else.

Then there’s the broader socialist tradition, which attacked the capitalist work ethic and claimed “The Right to Be Lazy.” Here’s Paul LaFargue back in 1883:

Capitalist ethics, a pitiful parody on Christian ethics, strikes with its anathema the flesh of the laborer; its ideal is to reduce the producer to the smallest number of needs, to suppress his joys and his passions and to condemn him to play the part of a machine turning out work without respite and without thanks.

And LaFargue criticized both economists (who “preach to us the Malthusian theory, the religion of abstinence and the dogma of work”) and workers themselves (who invited the “miseries of compulsory work and the tortures of hunger” and need instead to forge a brazen law forbidding any man to work more than three hours a day, the earth, the old earth, trembling with joy would feel a new universe leaping within her”).

Today, in the United States and around the world, the capitalist work ethic still prevails.

Workers are exhorted to search for or keep their jobs, even as wage increases fall far short of productivity growth, inequality (already obscene) continues to rise, new forms of automation threaten to displace or destroy a wage range of occupations, unions and other types of worker representation have been undermined, and digital work increasingly permeates workers’ leisure hours.

The world of work, already satirized by LaFargue and others in the nineteenth century, clearly no longer works.

Not surprisingly, the idea of a world without work has returned. According to Andy Beckett, a new generation of utopian academics and activists are imagining a “post-work” future.

Post-work may be a rather grey and academic-sounding phrase, but it offers enormous, alluring promises: that life with much less work, or no work at all, would be calmer, more equal, more communal, more pleasurable, more thoughtful, more politically engaged, more fulfilled – in short, that much of human experience would be transformed.

To many people, this will probably sound outlandish, foolishly optimistic – and quite possibly immoral. But the post-workists insist they are the realists now. “Either automation or the environment, or both, will force the way society thinks about work to change,” says David Frayne, a radical young Welsh academic whose 2015 book The Refusal of Work is one of the most persuasive post-work volumes. “So are we the utopians? Or are the utopians the people who think work is going to carry on as it is?”

I’m willing to keep the utopian label for the post-work thinkers precisely because they criticize the world of work—as neither natural nor particularly old—and extend that critique to the dictatorial powers and assumptions of modern employers, thus opening a path to consider other ways of organizing the world of work. Most importantly, post-work thinking creates the possibility of criticizing the labor involved in exploitation and thus of creating the conditions whereby workers no longer need to succumb to or adhere to the distinction between necessary and surplus labor.

In this sense, the folks working toward a post-work future are the contemporary equivalent of the “communist physiologists, hygienists and economists” LaFargue hoped would be able to

convince the proletariat that the ethics inoculated into it is wicked, that the unbridled work to which it has given itself up for the last hundred years is the most terrible scourge that has ever struck humanity, that work will become a mere condiment to the pleasures of idleness, a beneficial exercise to the human organism, a passion useful to the social organism only when wisely regulated and limited to a maximum of three hours a day; this is an arduous task beyond my strength.

And there’s a third tradition, one that directly contests the idea that participating in wage-labor is intrinsically dignified.

According to Friedrich Nietzsche (in his 1871 preface to an unwritten book, “The Greek State”), the dignity of labor was invented as one of the “needy products of slavedom hiding itself from itself.” That’s because, in Nietzsche’s view (following the Greeks), labor is only a “painful means” for existence and existence (as against art) has no value in itself. Therefore, “labour is a disgrace.”

Accordingly we must accept this cruel sounding truth, that slavery is of the essence of Culture; a truth of course, which leaves no doubt as to the absolute value of Existence. This truth is the vulture, that gnaws at the liver of the Promethean promoter of Culture. The misery of toiling men must still increase in order to make the production of the world of art possible to a small number of Olympian men.

And if slaves—or, today, wage-workers—no longer believe in the “dignity of labour,” it falls to the likes of both conservatives and liberals to ignore the “disgraced disgrace” of labor and create the necessary “conceptual hallucinations.” And then, on that basis, to suggest the appropriate government policies such that the “enormous majority [will], in the service of a minority be slavishly subjected to life’s struggle, to a greater degree than their own wants necessitate.”

Nietzsche believed that, in the modern world, the so-called dignity of labor was one of the “transparent lies recognizable to every one of deeper insight.” Apparently, neither wing of mainstream economists (nor, for that matter, many today on the liberal-left) has been able to formulate or sustain such insight.

Contesting the utopianism of full employment with a different utopian horizon creates the possibility of imagining and creating a different world—in which work acquires different meanings, in which the distinction between necessary and surplus is redefined and perhaps erased, and for the first time in modern history workers are no longer forced to have the freedom to sell their ability to work to someone else and achieve the right to be lazy.

*The Bureau of Labor Statistics calculates the labor force participation rate as the share of the 16-and-over civilian noninstitutional population either working or willing to work. Simply put, it is the portion of the population that is currently employed or looking for work. It differs from both the unemployment rate (the number of unemployed divided by the civilian labor force) and the employment-population ratio (the ratio of total civilian employment to the 16-and-over civilian noninstitutional population).