From David Ruccio There aren’t many ways ordinary Americans have a say in what happens to the surplus that determines their fate. Most of the surplus in the United States is appropriated by the boards of directors of large corporations. But most employees are excluded from the decisions in their workplaces about what’s done with that surplus. Their local communities, where the corporations operate, don’t have much of a say either. That leaves federal taxes. Corporate income taxes are pretty much the only way the nation—and therefore its citizen-workers—can lay claim to a share of the surplus, which it can then use to finance government programs. Given the tremendous growth in corporate profits in recent decades—including in recent years, during the recovery from the Second Great

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

There aren’t many ways ordinary Americans have a say in what happens to the surplus that determines their fate.

Most of the surplus in the United States is appropriated by the boards of directors of large corporations. But most employees are excluded from the decisions in their workplaces about what’s done with that surplus. Their local communities, where the corporations operate, don’t have much of a say either.

That leaves federal taxes. Corporate income taxes are pretty much the only way the nation—and therefore its citizen-workers—can lay claim to a share of the surplus, which it can then use to finance government programs.

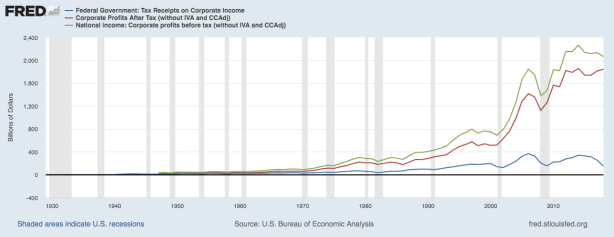

Given the tremendous growth in corporate profits in recent decades—including in recent years, during the recovery from the Second Great Depression—taxes on corporate profits should have been sufficient to expand existing government programs, create new ones, and even close the deficit.

But that hasn’t happened. Not at all. As is clear from the chart above, while corporate profits (both before and after taxes) have soared, the tax receipts on corporate income have actually declined.

Corporations can thank Donald Trump and the Republicans for that.

According to a new study by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, the so-called Tax Cuts and Jobs Act signed by Trump at the end of 2017 lowered the statutory federal corporate income tax rate to 21 percent (a 40-percent decrease from the previous 35 percent rate), in addition to other tax advantages and loopholes. But the actual results were even more obscene: profitable American corporations in 2018 collectively paid an average effective federal income tax rate of 11.3 percent, barely more than half the 21 percent statutory tax rate. And, as I showed a couple of weeks ago, 60 corporations paid no federal tax on their 2018 profits at all.*

In other words, corporations are appropriating more and more surplus from their workers but they’re being forced, via the federal tax code, to give up less and less of that surplus to the federal government to finance much-needed social programs for workers and their families.

But, lest we forget, it’s not just about Trump and his Republican enablers in Congress. The slide in corporate taxes has been going on for decades now.

As readers will see in the chart above, the share of federal revenues that come from taxes on corporate profits (the red line) has been declining since the mid-1950s, when it was above 30 percent. Now, it is only 6 percent.** One result is that Americans, through their government, have a smaller and smaller claim on the surplus that is captured by U.S. corporations.

The other result is that the share of the other two main sources of federal tax revenues—social insurances and taxes on individual incomes—has risen. But, even there, the claim on the surplus is declining.

For example, corporations are required to pay only half of Social Security (6.2 percent) and Medicare (1.45 percent) taxes and employees themselves the other half. That, of course, places a severe limit on the share of the surplus that goes to financing social insurance programs.

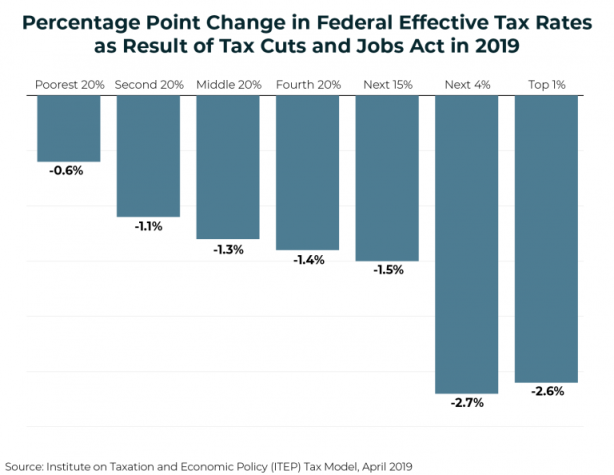

The single largest category of federal tax revenues consists of taxes on individuals, most of whom do not receive a cut of the surplus. Those at the top, however, do—but their tax rates are declining even more than everyone else’s.

According to another study by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, the 2017 Trump tax cut reduced the federal effective tax rate by 2.6 percentage points for the top 1 percent and by 2.7 for the next richest four percent. For all other income groups, the federal effective rate decreased by far less than 2 percentage points. Not only did the Trump tax cut result in a less progressive tax system, it also reduced the share of taxes on the surplus that is distributed to individuals.

Under Trump, but also for decades now, the nation’s claim on the surplus has been declining. Corporations and wealthy individuals, who benefit the most from government programs, have been able to shield more and more of the surplus they’ve been able to capture from federal taxes. That shifts the burden of federal taxation (not to mention the other taxes they pay, such as social insurance and local property and sales taxes) onto the nation’s workers. They’re the ones who produce the surplus but, over time, they have less and less of a claim on what is done with that surplus.

American workers have long been excluded from decisions over the surplus in their workplaces and communities. Now, at the federal level, they have a smaller say in even the amount of the surplus that is being taxed for government programs.

Workers are therefore increasingly dependent on the decisions of private corporations and wealthy individuals who manage to capture and, via the tax code, keep a larger share of the surplus. They, and not ordinary citizens, get to decide what to do with the surplus—a fundamental imbalance that, over time, has made American society even more unequal.

*According to the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, another 56 companies paid effective tax rates between 0 percent and 5 percent on their 2018 income. Their average effective tax rate was 2 percent.

**In 2018, and therefore attributable to the Trump tax cut, the share dropped from 9 percent.