From Dean Baker We are still very much in the middle of the pandemic, with the U.S. seeing tens of thousands of new infections daily, and the world experiencing hundreds of thousands of new infections. However, it is not too early to look at areas where we need to reevaluate public policy, most importantly in financing the research and development of new drugs and vaccines. The accepted wisdom in policy circles has been, that while the government can finance basic research, we need to rely on government-granted patent monopolies to pay for the actual development and testing of new drugs. The argument is that we want private companies to compete to develop new and better drugs, with the rents earned from their patent monopolies compensating them for the cost of research and testing, as

Topics:

Dean Baker considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from Dean Baker

We are still very much in the middle of the pandemic, with the U.S. seeing tens of thousands of new infections daily, and the world experiencing hundreds of thousands of new infections. However, it is not too early to look at areas where we need to reevaluate public policy, most importantly in financing the research and development of new drugs and vaccines.

The accepted wisdom in policy circles has been, that while the government can finance basic research, we need to rely on government-granted patent monopolies to pay for the actual development and testing of new drugs. The argument is that we want private companies to compete to develop new and better drugs, with the rents earned from their patent monopolies compensating them for the cost of research and testing, as well as compensating them for the risk that they will not develop a marketable drug.

The logic of this position relied on the claim that somehow government financing of the later stages of research and testing is essentially the same thing as throwing money in the toilet. The industry acknowledges the value of the research funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and in fact, is the biggest lobbyist for it. But they say that if NIH were to move downstream and actually finance the development of drugs and do clinical trials, they would turn into a bunch of bureaucratic bozos who couldn’t do anything right.[1]

The behavior of the government in this pandemic seems to indicate that this is not the case. The government, through Operation Warp Speed, is directly funding the research on vaccines, as the research takes place. This is most visible with Moderna, the country’s leading contender to develop a vaccine. The government paid $483 million to Moderna for pre-clinical research and Phase 1 and 2 testing. It then coughed up another $472 million to cover the cost of phase 3 testing.

If any policy types thought this direct government funding of the research and development of a vaccine was just throwing money in the toilet, they have not been very visible in expressing this view over the last four months. It is true that Moderna will also get a patent monopoly, allowing it to collect even more money for its effort, but the direct funding from the government is clearly the key here. This funding paid for the research and testing. It also meant that the government took all the risk. If Moderna’s vaccine turns out to be ineffective, the government will be out of the money, not Moderna.

Since policy types can apparently accept that when the federal government directly pays for the development and testing of new drugs and vaccines it is not the same as throwing the money into the toilet, maybe we can move forward and ask the next question as to how efficient direct public funding is relative to patent monopoly financed research. The issue here is how much the government would have to spend on advanced funding to get the same results as we see with patent monopoly financed research.

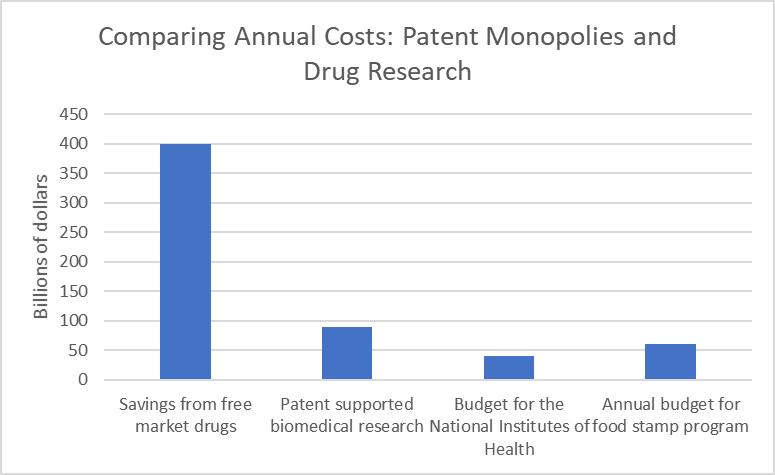

Before considering what the ratio of relative effectiveness might be, it is worth getting some idea of what is at stake. We will spend over $500 billion in 2020 for drugs that would almost certainly cost us less than $100 billion in a free market without patent monopolies or other forms of exclusivity.[2] It is rare that drugs are actually expensive to manufacture and distribute. The drugs that sell for tens of or even hundreds of thousands of dollars for a year’s treatment would typically sell for just a few hundred dollars if they were sold in a free market without patents or related protections. The potential savings of $400 billion a year come to more than $3000 per household.

In exchange for this $400 billion in higher drug prices, we get around $90 billion in research spending by the industry. These numbers are shown in the figure below, along with the $40 billion annual budget (pre-pandemic) for the National Institutes of Health. This is an understatement of federally funded biomedical research since we spend several billion more through the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) and other government agencies.

These figures are shown below along with the $60.4 billion that we spent on food stamps (SNAP) in 2019. The food stamp budget is included as a point of reference since many people in policy debates seem to believe that our spending on food stamps is a really big deal.

Source: Author’s calculations: see text.

Anyhow, the basic story is that we come out ahead with publicly funded research if it is at least one quarter as productive as patent monopoly supported the research. In other words, if four dollars of direct publicly funded research is at least good as one dollar of patent supported research, we would be better off switching to a system of publicly supported research.

There are actually good reasons for thinking that on a per-dollar basis government funding would be more efficient. First and foremost, the government could make it a condition of funding that all results are posted on the Internet as quickly as practical. This would allow researchers to quickly learn from each other’s work, building on successes and not wasting effort pursuing dead ends. This was the practice with the Bermuda Principles in the Human Genome Project. This sort of open-research in the early days after the coronavirus was first discovered led to much more rapid progress than would ordinarily be the case.

The other major reason why publicly funded, open-source, research is likely to be more efficient on a per-dollar basis is that there would be no incentive to develop copycat drugs as a way of sharing patent rents. While it is often desirable to have more than one drug to treat a specific condition since some patients may respond poorly to an initial drug or it could have harmful side effects, trying to engineer around a patent will generally not be a productive use of resources from a social standpoint. If research funding was being paid upfront, with no patent rents to compete over, there would be no incentive to develop a duplicative drug, except where there was a medical reason.

This raises another reason for believing that direct funding of research will lead to better health outcomes than our current system of patent monopoly financing. When drug companies can sell their drugs at patent monopoly prices they have an enormous incentive to promote their drug even in circumstances where it may not be the best treatment for a specific medical condition. This means that they have a reason to conceal evidence that their drugs may not be as effective as claimed or could even be harmful.

We saw this story with the opioid crisis, where several major pharmaceutical companies are alleged to have misled doctors and the public about the addictiveness of their new generation of opioids. Unfortunately, this is not an exception. There have been many instances where drug companies paid large settlements over allegations that they deliberately misled doctors and patients about the safety and effectiveness of their drugs.

In the absence of patent monopolies, no one would have any substantial incentive to make misleading claims about the quality of drugs. Furthermore, since all the research and test results would be fully public, they would likely not be able to get away with false claims even if they tried.

There is one additional source of waste that would be eliminated if we directly funded the research and allowed drugs to be sold at free market prices. We would not need insurance to cover drug costs. When drugs can cost, hundreds, thousands, or even tens of thousands of dollars, people need insurance to cover this potential expense. However, if most drugs sold for ten or twenty dollars per prescription, insurance would not really be needed. (Lower-income people would still need assistance in paying for drugs.)

Since insurers take on average 20 to 25 percent of health care spending to cover their administrative costs and profits, having drugs sell at free market prices would save us tens of billions annually on insurance costs. This also has to be factored into any comparison of the relative efficiency of direct public funding and patent monopoly financing.

If we do consider direct public financing of research, the Trump administration has not provided us with the best model. We don’t want companies selected through a closed door process with no clear criteria. My ideal model would be to have companies contracting for large sums to pursue research in specific areas for a substantial period of time. For example, a company may get a contract for $20 billion over a twelve-year period to pursue research for new drugs to treat liver cancer.

This sort of long-term contracting should insulate companies for political pressure, since once a contract was granted, they could not lose the funding, barring outright fraud or other serious forms of malfeasance. The awarding and renewal of contracts would be based on clear and fully public criteria. (This system is described more fully in chapter 5 of Rigged.)

It will be a long jump from where we are now to a system of open-source publicly financed biomedical research, but we opened the door for this switch with the financing of treatments and vaccines for the coronavirus. Once we acknowledge that direct public funding of the development of new drugs is not the same thing as throwing money into the toilet, then we can start asking questions about the relative effectiveness of direct public funding and patent supported research.

This seems to raise uncomfortable questions for many people in policy debates. They, and their friends and family, tend to be among the group of people who benefit from patent and copyright monopolies in drugs and other areas. However, if we want to have serious policy discussions, and not just protect existing patterns of inequality, government-granted patent and copyright monopolies have to be on the table.

[1] This view persists in spite of the fact that many important drugs have actually been developed on NIH grants and the agency has financed hundreds of clinical trials.

[2] There are a variety of mechanisms other patent monopolies that allow drug companies to have exclusive rights to sell a drug. The most important of these is data exclusivity, which prohibits generic manufacturers from relying on the test data from a brand drug to show that a chemically equivalent drug is safe and effective.