From David Ruccio Mainstream economists and commentators, it seems, are worried that the global economy is going to come crashing down as a result of the COVID crisis. That’s why they’re willing now to consider the possibility that the current crisis is more than a normal recession, more serious even than the so-called Great Recession; in their view, it’s an economic depression. That, at least, is the argument they present up front. But there’s something else going on, which haunts their analysis—that capitalism itself is now being called into question. But before we get to that alarming specter, let’s take a look at the logic of their analysis about the current perils to the global economy—starting with the Washington Post columnist Robert J. Samuelson, who is basically taking his

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

Mainstream economists and commentators, it seems, are worried that the global economy is going to come crashing down as a result of the COVID crisis. That’s why they’re willing now to consider the possibility that the current crisis is more than a normal recession, more serious even than the so-called Great Recession; in their view, it’s an economic depression.

That, at least, is the argument they present up front. But there’s something else going on, which haunts their analysis—that capitalism itself is now being called into question.

But before we get to that alarming specter, let’s take a look at the logic of their analysis about the current perils to the global economy—starting with the Washington Post columnist Robert J. Samuelson, who is basically taking his cues from a recent essay in Foreign Affairs by Carmen Reinhart and Vincent Reinhart.*

Their shared view is that the current slowdown is both more severe and more widespread than the crash of 2007-08, and the recovery will be much slower. Therefore, they argue, the COVID crisis represents the worst economic downturn since the Great Depression of the 1930s.

This is a big deal: mainstream economists and commentators are uneasy about invoking the term “economic depression.” They certainly resisted it for the crisis that occurred just over a decade ago, eventually devising a Goldilocks nomenclature, dubbing it the Great Recession (not as hot as the Great Depression but not as cold as a normal recession). As regular readers know, I had no compunction about calling it the Second Great Depression. And, according to their own logic, neither Samuelson nor the Reinharts should have either.

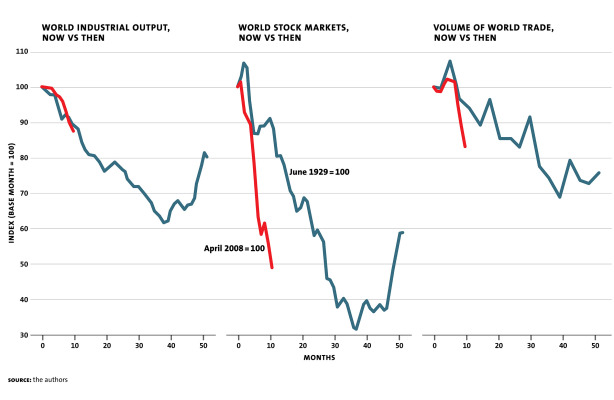

According to Barry Eichengreen and Kevin O’Rourke, the financial crisis and recession had led to as big a downward shock to global industrial production in 2008 as the 1929 financial crisis, and had pounded stock market values and world trade volumes harder in 2008-09 than in 1929-30. Thus, from the perspective of the magnitude of the initial shock, the global economy was in at least as dire shape after the crash of 2008 as it had been after the crash of 1929.

Moreover, the downturn that began in 2007-08 was “largely a banking crisis” (as the Reinharts put it) only if they ignore the grotesque levels of inequality that preceded the crash (based on stagnant wages and rising profits)—which in turn fueled the need for credit on the part of workers and the growth of the finance sector that both recycled corporate profits to workers in the form of loans and led to even higher profits, creating in the process a veritable house of cards. At some point, it would all come crashing down. And, eventually, it did.

In any case, Samuelson and the Reinharts are now willing to take the next step and use the dreaded d-word to characterize current events. Here’s how the Reinharts see things:

In its most recent analysis, the World Bank predicted that the global economy will shrink by 5.2 percent in 2020. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics recently posted the worst monthly unemployment figures in the 72 years for which the agency has data on record. Most analyses project that the U.S. unemployment rate will remain near the double-digit mark through the middle of next year. And the Bank of England has warned that this year the United Kingdom will face its steepest decline in output since 1706. This situation is so dire that it deserves to be called a “depression”—a pandemic depression.

And Samuelson does them one better:

In one respect, the Reinharts have underestimated the parallels between the today’s depression and its 1930s predecessor. What was unnerving about the Great Depression is that its causes were not understood at the time. People feared what they could not explain. The consensus belief was that business downturns were self-correcting. Surplus inventories would be sold; inefficient firms would fail; wages would drop. The survivors of this brutal process would then be in a position to expand.

Something similar is occurring today.

Clearly, Samuelson and even more the Reinharts are worried that the global economy—their cherished vision of the free movement of capital (but not people) and expanding trade according to comparative advantage—is currently being imperiled and may not recover for years to come. The volume of world trade is down; the prices of many exports have fallen; corporate debt is climbing; and the reserve army of unemployed and underemployed workers is massive and still growing. The prospects for a return to business as usual are indeed remote.

That’s pretty straightforward stuff, and anyone who’s looking at the numbers can’t but agree. What we’re witnessing is in fact a Pandemic—or, in my view, a Third Great—Depression.

But that’s when things start to get interesting. Because the Reinharts do understand (although I doubt Samuelson does, since he’s really only concerned about government deficits) that, when you resurrect the term depression and invoke the analogy of the 1930s, you also call forth widespread discontent, massive protest movements, and challenges to capitalism itself. Here’s how they see it:

The economic consequences are straightforward. As future income decreases, debt burdens become more onerous. The social consequences are harder to predict. A market economy involves a bargain among its citizens: resources will be put to their most efficient use to make the economic pie as large as possible and to increase the chance that it grows over time. When circumstances change as a result of technological advances or the opening of international trade routes, resources shift, creating winners and losers. As long as the pie is expanding rapidly, the losers can take comfort in the fact that the absolute size of their slice is still growing. For example, real GDP growth of four percent per year, the norm among advanced economies late last century, implies a doubling of output in 18 years. If growth is one percent, the level that prevailed in the shadow of the 2008–9 recession, the time it takes to double output stretches to 72 years. With the current costs evident and the benefits receding into a more distant horizon, people may begin to rethink the market bargain.

Now, it’s true, their stated fear is that “populist nationalism” will disrupt multilateralism, open economic borders, and the free flow of capital and goods and services across national boundaries. That’s as far as their stated thinking can go.

But the apparition that lurks in the background is that rethinking the “market bargain”—what elsewhere I have called the “pact with the devil,” that is, giving control of the surplus to the top 1 percent as long as they made decisions to create jobs, fund schools and healthcare, and be able to tackle problems like the novel coronavirus pandemic so that the majority of people could lead decent lives—will mean expanding criticisms of capitalism and the search for radical alternatives.

That’s the real specter that haunts the Pandemic Depression.

*Samuelson sees the wife-and-husband Reinharts as “heavy hitters” among economists: “She is a Harvard professor, on leave and serving as the chief economist of the World Bank; he was a top official at the Federal Reserve and is now chief economist at BNY Mellon.”