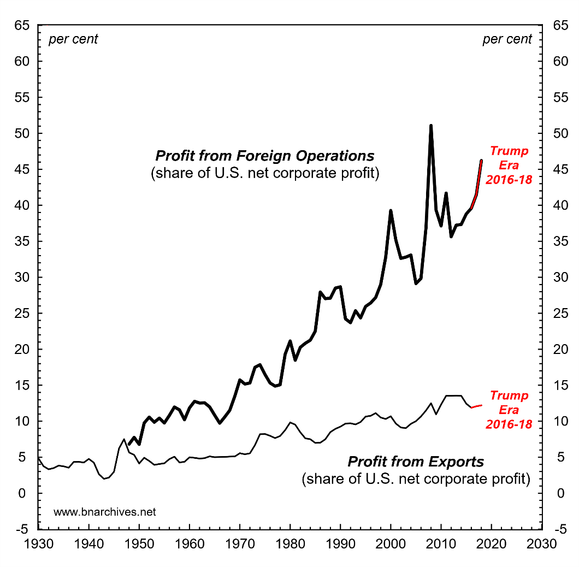

From Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan and RWER issue #90 On the whole, then, the global decline of so-called American firms is not an accounting gimmick or an exchange-rate artefact. It is a real process with real causes and real consequences. And paradoxically, this decline is intimately related to a seemingly opposite process: the growing dependency of these very “American” firms on foreign operations. This latter dependency is shown in Figure 4. The top series measures the share of U.S. corporate profit coming from foreign subsidiaries, while the bottom series estimates the share earned from exports. Figure 4 U.S. Corporate Dependency on Foreign Profit: Foreign Operations vs Exports NOTE: This chart is revised and updated from Nitzan and Bichler (2009: Figure 15.6, p. 357).

Topics:

Editor considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan and RWER issue #90

On the whole, then, the global decline of so-called American firms is not an accounting gimmick or an exchange-rate artefact. It is a real process with real causes and real consequences. And paradoxically, this decline is intimately related to a seemingly opposite process: the growing dependency of these very “American” firms on foreign operations.

This latter dependency is shown in Figure 4. The top series measures the share of U.S. corporate profit coming from foreign subsidiaries, while the bottom series estimates the share earned from exports.

Figure 4 U.S. Corporate Dependency on Foreign Profit: Foreign Operations vs Exports

NOTE: This chart is revised and updated from Nitzan and Bichler (2009: Figure 15.6, p. 357). Profit from foreign operations denotes receipts from the rest of the world as a per cent of corporate profit after tax. Profit from exports is estimated by the export share of GDP. The last data points are for 2018.

SOURCE: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis through Global Insight (series codes: ZBECONRWRCT for after-tax corporate profit receipts from the rest of the world; ZA for after-tax corporate profit; X for exports; GDP for GDP).

In the mid-1940s, both measures hovered around 7 per cent. The United States was still a relatively closed economy with an expanding population, rising “real” wages and rapidly growing GDP per capita. In this context, U.S. firms looked mostly inward, earning over 85 per cent of their profit from domestic operations.

But the relentless drive of large firms to augment their capitalized power over the underlying population mandated “strategic sabotage” in the form of rising unemployment and slowing growth (as examined in Nitzan and Bichler, 2014; see also the animation by Thouvenot, 2019), while their quest for differential accumulation relative to lesser firms set in motion a merger and acquisition uptrend that eventually made them “too big” for the decelerating U.S. market (Nitzan, 2001; Nitzan and Bichler, 2009, Part V).

This differential power process, we argue, is key to understanding the exponential rise in the share of corporate profit from foreign operations shown by the top series in Figure 4. Having exhausted the most lucrative takeover targets in their home country, and with their home country stagnating and therefore not generating new takeover targets at a fast enough rate, large U.S. firms have had no choice but to break the national envelope and go global. They started taking over foreign firms at an ever increasing rate (most FDI occurs via mergers and acquisitions rather than greenfield investment), and as the process accelerated the share of foreign profit rose dramatically. Foreign operations currently account for roughly half of all U.S. corporate profit, and if the uptrend persists the so-called American firm will soon become a misnomer. read more