In January 1980 Jimmy Carter enacted a grain export embargo against the Soviet Union because of the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. The embargo was ineffective as the resulting gap in Soviet imports, at the time and for quite some years to come a net grain importer, was filled by countries like Argentina. In 2022 things have changed. After 2000, Russia as well as Ukraine became major grain exporters, playing an important role in global food supply chains. In both countries production as well as exports have increased by leaps and bounds, which was enabled by increases in acreage and yields (graph 1 for wheat, graph 2 for maize). All data from this source. The invasion of Ukraine and the ensuing war will disrupt these chains not by halting imports but by disrupting production and

Topics:

Merijn T. Knibbe considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

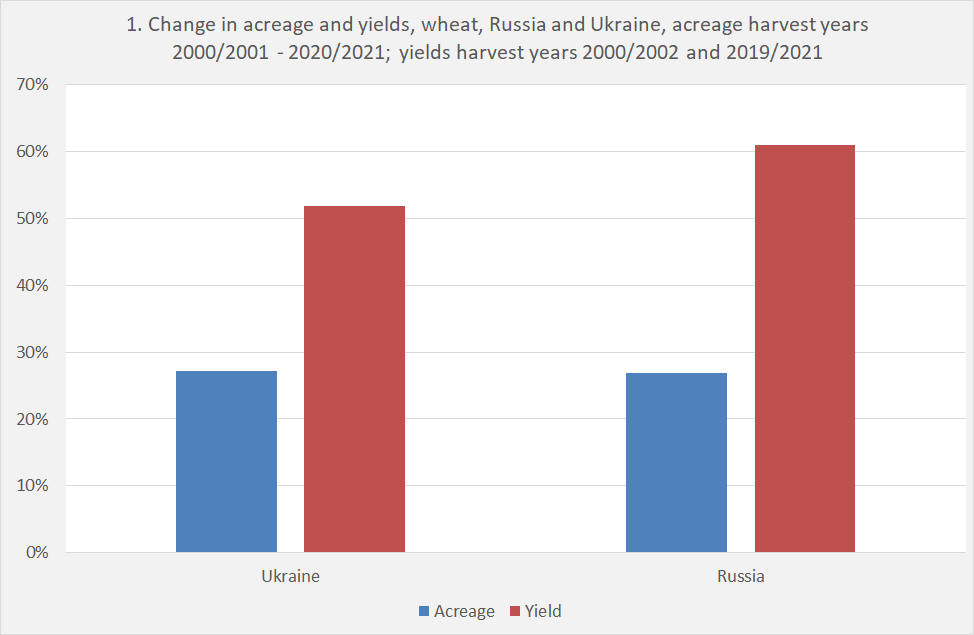

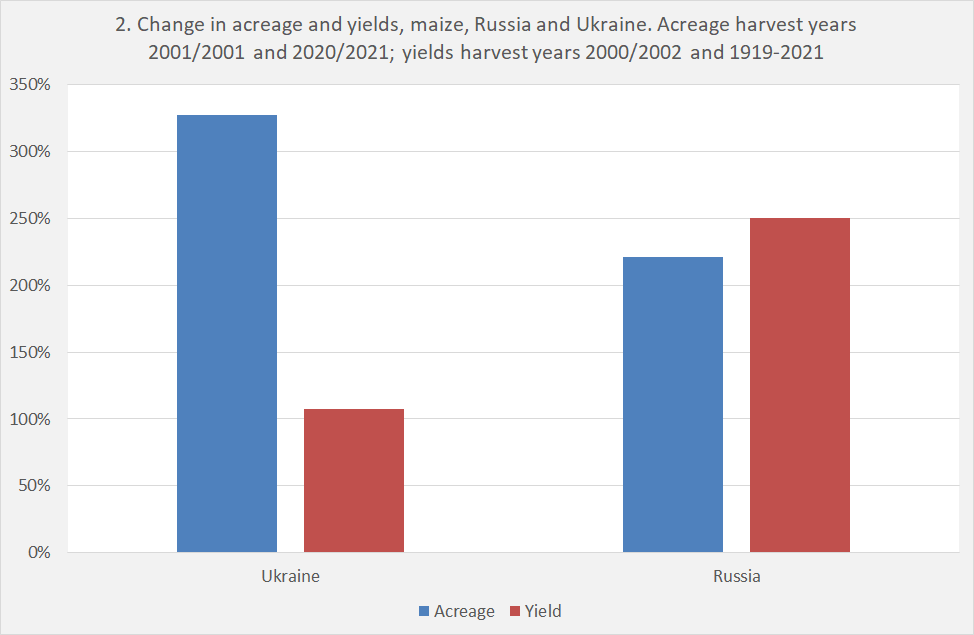

In January 1980 Jimmy Carter enacted a grain export embargo against the Soviet Union because of the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. The embargo was ineffective as the resulting gap in Soviet imports, at the time and for quite some years to come a net grain importer, was filled by countries like Argentina. In 2022 things have changed. After 2000, Russia as well as Ukraine became major grain exporters, playing an important role in global food supply chains. In both countries production as well as exports have increased by leaps and bounds, which was enabled by increases in acreage and yields (graph 1 for wheat, graph 2 for maize). All data from this source. The invasion of Ukraine and the ensuing war will disrupt these chains not by halting imports but by disrupting production and exports of grain (even when at the time of writing trucks with agricultural seeds are still driving from the Netherlands to Russia (private information)).

In fact the disruption of food security has already happened. Despite record harvests, the post 2014 conflict in eastern Ukraine caused food insecurity and malnourishment for millions, underscoring the well known fact that hunger and malnutrition is a problem of distribution and entitlements and provision, not of production. The coexistence of domestic shortages and hunger with exports of food grains can, in an historical context, be compared with the Irish famine even when the situation in Ireland was rationalized by extreme free market ideologies while the situation in Eastern Ukraine was rationalized with extreme nationalist mythologies. In both cases, great power politics disrupted production and distribution.

Anyway, as a result of the spectacular increase in production and despite war related shortages in Ukraine itself supply chains have changed as spectacular. In just a couple of years Russia as well as Ukraine have become major exporters of grain (graph 3) and countries like Egypt and Turkey are highly dependent on imports of ‘black earth’ grain, while on the other side of the supply chain producers of seeds and fertilizers and all kind of pesticides have a good time, too. Total wheat and maize exports of Ukraine and Russia increased from almost zero to 20 and even 30% of total global exports in only two decades. Dazzling. Increases of agricultural yields of 100 to 250% in two decades in combination with increases in acreages which are as large or even larger are ‘of the scale’. And the potential for additional growth seems high- a good thing, considering a global population which is supposed to increase with another 2 billion people during the next four decades (as long as between 1980 and now). In a historical perspective this can only be compared with the increase in global supply which took place when, after the end of the Civil War, the production of grains in combination with cheap mass transport led to a substantial increase of availability of food in Europe and, as food prices declined, quit an increase of real income as well as an improvement of health of the population. The fast increase in agricultural output of Russia and Ukraine must be rated to be one of the most significant global developments of the last two decades.

The invasion of Ukraine brings this to and end. It will lead to shortages and high prices which can not be countered by relying on market forces. Unless other producers step in these shortages might persist for many years – . High food prices will be especially detrimental to poor people. It will lead, even in the short run, to more malnutrition and worse health for untold millions of people. Alas, the rather Malthusian view of somebody like Andriy Yarmak can’t be dismissed: high energy prices will lead to higher prices of chemical fertilizers and transport, too. Which is why I consider disruptions to food production and supply chains to be a crime against humanity. Mind: during the neoliberal epoch, much time and effort and intelligence and political power was spent on guaranteeing the rights and wealth of capital owners, especially against the background of the globalisation of production and supply chains (see the work of Quinn Slobodian). More attention has to be spent on the interests of workers, farmers and consumers even if this comes at the cost of capital owners or, to be more precise, in this case the owners of the land – and not just the land in Ukraine and Russia. In the end, high agricultural prices are a boon for landowners, which can charge ever higher rents , not for farmers (unless these own the land). Considering the brutality of present events, this all might sound more than a bit idealistic. But we do need to counter nationalist perspectives and mythologies. We still need the idea that ‘producing stuff is glorious’, surely, but not only, when it comes to food. We can do it, we need to do it.