Some time ago, I delved into the unique advantages of the Theil index of inequality over the Gini index, when data is available. The Theil index offers a distinct advantage in its ability to provide a consistent quantitative deconstruction of inequality. It does so by utilizing various concepts such as class, region, gender, or any other relevant factor. This feature allows for a comprehensive explanation of (changes in) inequality using the same set of concepts. The Theil index enables us to quantify: Within-group inequality Between-group inequality Michiel de Haas provides a teachable example of how to do this and how to analyse such information in his article ´Reconstructing income inequality in a colonial cash crop economy: five social tables for Uganda, 1925–1965´in the

Topics:

Merijn T. Knibbe considers the following as important: colonialism, Economics, economy, history, inequality, theil-index, Uganda, Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Jeremy Smith writes UK workers’ pay over 6 years – just about keeping up with inflation (but one sector does much better…)

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Schuldenbremse bye bye

Lars Pålsson Syll writes What’s wrong with economics — a primer

Some time ago, I delved into the unique advantages of the Theil index of inequality over the Gini index, when data is available. The Theil index offers a distinct advantage in its ability to provide a consistent quantitative deconstruction of inequality. It does so by utilizing various concepts such as class, region, gender, or any other relevant factor. This feature allows for a comprehensive explanation of (changes in) inequality using the same set of concepts.

The Theil index enables us to quantify:

- Within-group inequality

- Between-group inequality

Michiel de Haas provides a teachable example of how to do this and how to analyse such information in his article ´Reconstructing income inequality in a colonial cash crop economy: five social tables for Uganda, 1925–1965´in the European Review of Economic History 26-2, May 2022, 255–283.

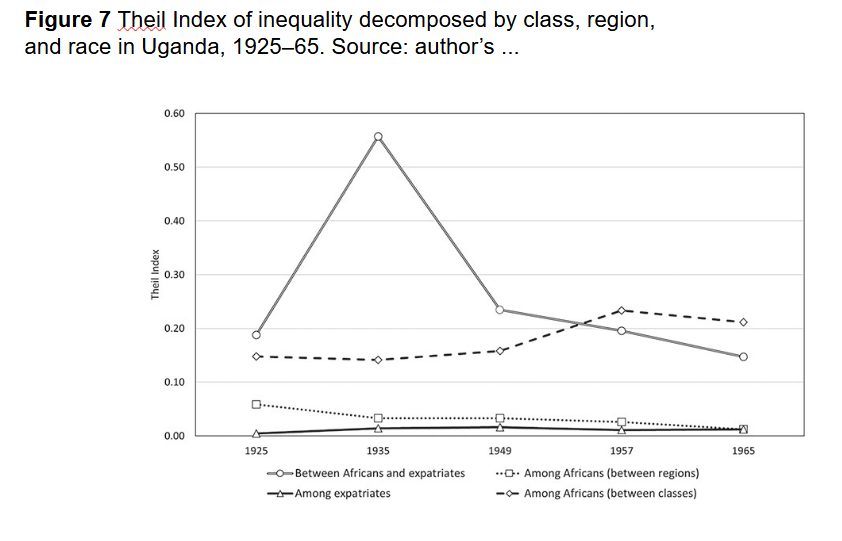

In his ´Figure 7´ he shows the historical evolution of the contribution of inequality among (´within´) different groups and between different groups in Uganda. As I do not intend to write something about Ugande but something about how to use the Theil index, I will only discuss one aspect of this graph: the extraordinarily high contribution of ´Between Africans and expatriates´ contribution to total inequality in 1935. The Theil index allows us to show this. But it also leads us on the path to analysing this event using the same concepts. What happened?

De Haas explains this remarkable even by pointing out an increased rate of exploitation:

A closer look at the income development of Europeans shows that they not only saw incomes rise relative to African Ugandans (figure 9) but also relative to average earnings in the United Kingdom (figure 11), and in real terms, using the British retail price index as a deflator (figure 12). This particularly favorable European income development during the 1930s was not specific to Uganda, but is also found in Botswana and Ghana, which, like Uganda, were British colonies with sizeable indigenous agricultural export sectors where the far majority of Europeans worked as government employees (Bolt and Hillbom 2016; Aboagye and Bolt 2020)…. For Uganda, various scholars have remarked (albeit mostly in passing) on the increased economic extraction of African farmers during the 1930s. The Depression years saw a substantial increase of the real tax burden on African households, as poll tax rates were largely maintained, despite falling cash crop incomes (De Haas 2017, 618). Moreover, markets for cotton, then by far Uganda’s most important cash crop, were increasingly regulated through price fixing and zoning, which hurt African growers and benefited Uganda’s ginneries, which were exclusively owned by Europeans and Asians at that time (Ehrlich 1958; Jamal 1976).

The remarkably high wages provided to European government officials and the perks given to Uganda’s expatriate ginners through price fixing and zoning propped up European administrative and entrepreneurial activity in British African colonies during the crisis years. The African self-employed economy absorbed much of the adverse price shock.

Returning to the Theil index, it enables us to focus on such developments and provide a measured-variables consistent measurement and explanation of changes in inequality. Using the Gini index doesn´t.