This post was written because of a tweet by David Andalfatto, who wondered why medieval and early modern Europe, a society that built cathedrals, did not show any per capita growth. Per capita growth is an average, and when the rich get richer, it can increase even when the number of poor and destitute increases. The question is: was something like this the case in the time of the cathedrals? I won’t give a definite answer. But I will go beyond ´real´ GDP per capita (ultimately a monetary average) and delve into physical-technological, personalized development. And it´s all about glass (picture: ´Het straatje´ by Vermeer (1658?); at the end for comparison a picture of an 1820 street in Amsterdam). Glass windows were a great invention, enhancing the quality of houses and the

Topics:

Merijn T. Knibbe considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

This post was written because of a tweet by David Andalfatto, who wondered why medieval and early modern Europe, a society that built cathedrals, did not show any per capita growth. Per capita growth is an average, and when the rich get richer, it can increase even when the number of poor and destitute increases. The question is: was something like this the case in the time of the cathedrals? I won’t give a definite answer. But I will go beyond ´real´ GDP per capita (ultimately a monetary average) and delve into physical-technological, personalized development. And it´s all about glass (picture: ´Het straatje´ by Vermeer (1658?); at the end for comparison a picture of an 1820 street in Amsterdam).

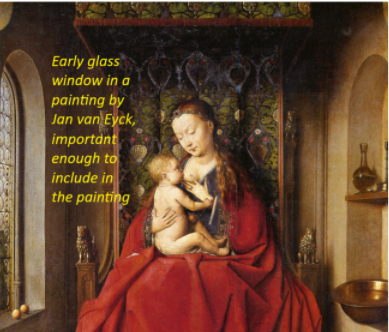

Glass windows were a great invention, enhancing the quality of houses and the indoor environment. As we all know, stained glass windows were part and parcel of the cathedrals as buildings and places of worship. No one less than Francois Villon, not just the greatest of the medieval poets, tells us about his illiterate mum:

Ballade Written for his Mother

Preserve me that my soul within

Finds joy where sorrow long hath bin,

Virgin, through whose grace even I

May touch God through the wafer thin.

And in this faith I live and die.

A poor old woman — old and lean —

Am I, who know not letters three,

Yet in the cloister have I seen

Heaven in those pictures heavenly.

Where saints and angels ever be

With harps and lutes, and, ‘neath their din,

A hell with sinners scorched of skin,

‘Twixt joy and fear to thee I fly

Who savest sinners from hell’s gin.

And in this faith I live and die.

However, inventions only alleviate the plight of the poor and the destitute when they become common. Wikipedia tells us that, in England, they only became common in the 17th century (even when the idea had been around since Roman times).

That may be true for England. Or there might be an obscure article from 1897 buried in the cellar of a country library in Kent which states otherwise. But for the Netherlands, it wasn’t true. Recently, Meindert Schroor published the 1541-1608 accounts of the Old Burgher Orphanage of the medium-sized city of Leeuwarden, since around 1500, the capital of Friesland, located in the North of the present country of the Netherlands. I’m putting the 1.200 pages of this transcription in Excel. Part of the plight of the unpaid volunteers making up the orphanage board (the organisation is still going strong) was maintaining the orphanage building and other real estate. As the number of orphans grew, a new building was necessary. After a successful fundraising campaign (no, this is not an anachronism), it was built in 1564. We now encounter the first two (!) ‘glaesemaeckers’ (window makers), Cryn Wytzez and Hette Hansz. Together, they earn no less than 21,85 Carolus guilders, equivalent to around 73 days of labour. Seven guilders and 12,5 stuivers were used to pay for lead, to frame the relatively small pieces of glass. The rest was used for labour and, of course, glass. A detail for Andalfatto, according to his twitter-bio former construction worker: on 22 June 1564 the ‘meiboom’ (wreath) was put on top of the wooden frame and, according to ‘ancient habit’, 30 stuivers (four to five labor days) was spent on liquidities. In the subsequent decades, window makers were paid repeatedly to repair windows and use lead and other materials to make them wind and waterproof, not just for the orphanage but also for some buildings owned by the orphanage.

These orphans were (with some exceptions) the children of ‘burghers’, inhabitants of the city with (at least when male) active and passive political rights and probably not the children of the most destitute and poor inhabitants. Even then, they were vulnerable. And cared for. In the modern national accounts, NPISH are Non-Profits Institutions Serving Households, like unions and churches, contributing to value added. The orphanage clearly was an NPISH, with a professional (i.e. paid and living inside the building) ‘inside mother’ as well as some servants. In contrast, the board and the ‘outside mothers’, who clearly had some jurisdiction over the orphanage, were volunteers.

I do not want to pay a rosy picture of early modern city life. Whole families died of the plague, and even when there were some sanitary installations in the orphanage, they weren´t in the ´chambers´. However, later entries in the accounts show that glass windows were also present in at least some of the one-room ‘chambers’ rented out by the orphanage. These ´chambers´ were often obtained through inheritances and often were as simple as they could be: cold, wet, leaking roofs. The boards did not like the hassle of being a landlord (maintenance, dying or suing renters, renters who would not or could not pay), considered renting out on a commercial basis not profitable and tried to sell them. Aside: one of them had, which is mentioned again and again, a reed roof, meaning it was just outside the city. Inside the city, to curb the dangers of fire, buildings had to have roof tiles, another innovation. But they did (as the last wills stipulated) provide some ‘chambers’ for free to ‘poor widows’ and also spent at least some money on maintaining these chambers. Including money to repair glass windows. 16th and 17th-century Friesland was an unequal society – but glass windows and roof tiles were not just for the rich (and it was possibly ahead England).

Returning to per capita GDP, the increase in the quality of at least some houses is, in my opinion, neglected in historical estimates of GDP. As in Leeuwarden, almost all houses were simple (wood, loam, reed, twigs) around 1500 but were improved during the 16th century (indeed, after the great fire at the beginning of the 16th century). This must have raised average (!) GDP, as is also shown by an increase of the distribution of labor (window making became a craft, there is no ´broken window fallacy´ even when repairing is maintenance and adds to Gross, but not Net Domestic Product). Fast forward to today: some houses in the slums of exploding cities in Africa and Asia are splendid. We have to investigate and measure this, historically and today. Also, this (picture: Johannis Hendrik Knoop, ca. 1820, Anjeliersstraat, Amsterdam) is what happens when people believe the ´broken window fallacy´ is true and repairing windows does not add to prosperity (what you see is a decrepit ´chamber´, glass windows, brick buildings, roof tiling, a rain gutter and the nefarious consequences of inadequate maintenance)