From Lars Syll Few issues in politics and economics are nowadays more discussed — and less understood — than public debt. Many raise their voices to urge for reducing the debt, but few explain why and in what way reducing the debt would be conducive to a better economy or a fairer society. And there are no limits to all the — especially macroeconomic — calamities and evils a large public debt is supposed to result in — unemployment, inflation, higher interest rates, lower productivity growth, increased burdens for subsequent generations, etc., etc. The standard mainstream textbook argument about budget deficits goes something like this: Assume that total output is given. If government expenditures are increased, then this has to be met by an equally large decrease in investment, which

Topics:

Lars Pålsson Syll considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from Lars Syll

Few issues in politics and economics are nowadays more discussed — and less understood — than public debt. Many raise their voices to urge for reducing the debt, but few explain why and in what way reducing the debt would be conducive to a better economy or a fairer society. And there are no limits to all the — especially macroeconomic — calamities and evils a large public debt is supposed to result in — unemployment, inflation, higher interest rates, lower productivity growth, increased burdens for subsequent generations, etc., etc.

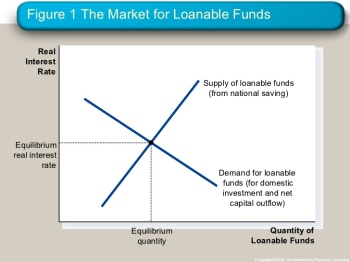

The standard mainstream textbook argument about budget deficits goes something like this: Assume that total output is given. If government expenditures are increased, then this has to be met by an equally large decrease in investment, which can only come forth by rising interest rates. ‘Crowding out’ reduces public saving and causes interest rates to rise. Then, applying the logic of the Solow growth model, it is concluded that (Mankiw, Macroeconomics, 8th ed., p. 221)

the long-run consequences of a reduced saving rate are a lower capital stock and lower national income. This is why many economists are critical of persistent budget deficits.

Now, what’s wrong with this? Everything! To a considerable extent, the reasoning is based on the loanable funds theory — which has no room for the simple fact that the rate of interest is not determined by the demand for and supply of capital since investment basically finances itself.

The loanable funds theory is in many regards nothing but an approach where the ruling rate of interest in society is — pure and simple — conceived as nothing else than the price of loans or credits set by banks and determined by supply and demand — as Bertil Ohlin put it — “in the same way as the price of eggs and strawberries on a village market.”

It is a beautiful fairy tale, but the problem is that banks are not barter institutions that transfer pre-existing loanable funds from depositors to borrowers. Why? Because, in the real world, there simply are no pre-existing loanable funds. Banks create new funds — credit — only if someone has previously got into debt! Banks are monetary institutions, not barter vehicles.

It is a beautiful fairy tale, but the problem is that banks are not barter institutions that transfer pre-existing loanable funds from depositors to borrowers. Why? Because, in the real world, there simply are no pre-existing loanable funds. Banks create new funds — credit — only if someone has previously got into debt! Banks are monetary institutions, not barter vehicles.

In the traditional loanable funds theory — as presented in mainstream macroeconomics textbooks — the amount of loans and credit available for financing investment is constrained by how much saving is available. Saving is the supply of loanable funds, and investment is the demand for loanable funds and is assumed to be negatively related to the interest rate. Lowering households’ consumption means increasing savings via a lower interest.

That view has been shown to have very little to do with reality. It’s nothing but an otherworldly mainstream model fantasy. But there are many other problems as well with the standard presentation and formalization of the loanable funds theory:

• As already noticed by James Meade decades ago, the causal story told to explicate the accounting identities used gives the picture of “a dog called saving wagged its tail labelled investment.” In Keynes’s view — and later over and over again confirmed by empirical research — it’s not so much the interest rate at which firms can borrow that causally determines the amount of investment undertaken, but rather their internal funds, profit expectations and capacity utilization.

• As is typical of most mainstream macroeconomic formalizations and models, there is pretty little mention of real-world phenomena, like e. g. real money, credit rationing and the existence of multiple interest rates, in the loanable funds theory. Loanable funds theory essentially reduces modern monetary economies to something akin to barter systems — something they definitely are not. As emphasized especially by Minsky, to understand and explain how much investment/loaning/crediting is going on in an economy, it’s much more important to focus on the working of financial markets than staring at accounting identities like S = Y – C – G. The problems we meet on modern markets today have more to do with inadequate financial institutions than with the size of loanable-funds-savings.

• The loanable funds theory in the ‘New Keynesian’ approach means that the interest rate is endogenized by assuming that Central Banks can (try to) adjust it in response to an eventual output gap. This, of course, is essentially nothing but an assumption of Walras’ law being valid and applicable, and that a fortiori the attainment of equilibrium is secured by the Central Banks’ interest rate adjustments. From a realist Keynes-Minsky point of view, this can’t be considered anything else than a belief resting on nothing but sheer hope. [Not to mention that more and more Central Banks actually choose not to follow Taylor-like policy rules.] The age-old belief that Central Banks control the money supply has more and more come to be questioned and replaced by an ‘endogenous’ money view, and I think the same will happen to the view that Central Banks determine “the” rate of interest.

• A further problem in the traditional loanable funds theory is that it assumes that saving and investment can be treated as independent entities. This is seriously wrong:

The classical theory of the rate of interest [the loanable funds theory] seems to suppose that, if the demand curve for capital shifts or if the curve relating the rate of interest to the amounts saved out of a given income shifts or if both these curves shift, the new rate of interest will be given by the point of intersection of the new positions of the two curves. But this is a nonsense theory. For the assumption that income is constant is inconsistent with the assumption that these two curves can shift independently of one another. If either of them shifts, then, in general, income will change; with the result that the whole schematism based on the assumption of a given income breaks down … In truth, the classical theory has not been alive to the relevance of changes in the level of income or to the possibility of the level of income being actually a function of the rate of the investment.

There are always (at least) two parts to an economic transaction. Savers and investors have different liquidity preferences and face different choices — and their interactions usually only take place intermediated by financial institutions. This, importantly, also means that there is no ‘direct and immediate’ automatic interest mechanism at work in modern monetary economies. What this ultimately boils done to is — iter — that what happens at the microeconomic level — both in and out of equilibrium — is not always compatible with the macroeconomic outcome. The fallacy of composition (the ‘atomistic fallacy’ of Keynes) has many faces — the loanable funds theory is one of them.

• Contrary to the loanable funds theory, finance in the world of Keynes and Minsky precedes investment and saving. What is ‘forgotten’ in the loanable funds theory, is the insight that finance — in all its different shapes — has its own dimension, and if taken seriously, its effect on an analysis must modify the whole theoretical system and not just be added as an unsystematic appendage. Finance is fundamental to our understanding of modern economies and acting like the baker’s apprentice who, having forgotten to add yeast to the dough, throws it into the oven afterwards, simply isn’t enough.

All real economic activities nowadays depend on a functioning financial machinery. But institutional arrangements, states of confidence, fundamental uncertainties, asymmetric expectations, the banking system, financial intermediation, loan granting processes, default risks, liquidity constraints, aggregate debt, cash flow fluctuations, etc., etc. — things that play decisive roles in channelling money/savings/credit — are more or less left in the dark in modern mainstream formalizations of the loanable funds theory.