From Lars Syll According to Keynes, financial crises are a recurring feature of our economy and are linked to its fundamental financial instability: It is of the nature of organised investment markets, under the influence of purchasers largely ignorant of what they are buying and of speculators who are more concerned with forecasting the next shift of market sentiment than with a reasonable estimate of the future yield of capital-assets, that, when disillusion falls upon an over-optimistic and over-bought market, it should fall with sudden and even catastrophic force. Keynes believed that the financial system — necessary for a vibrant market economy by channelling the entrepreneurs’ animal spirits into investments — is also so unstable and sensitive that it easily falls into crisis.

Topics:

Lars Pålsson Syll considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from Lars Syll

According to Keynes, financial crises are a recurring feature of our economy and are linked to its fundamental financial instability:

It is of the nature of organised investment markets, under the influence of purchasers largely ignorant of what they are buying and of speculators who are more concerned with forecasting the next shift of market sentiment than with a reasonable estimate of the future yield of capital-assets, that, when disillusion falls upon an over-optimistic and over-bought market, it should fall with sudden and even catastrophic force.

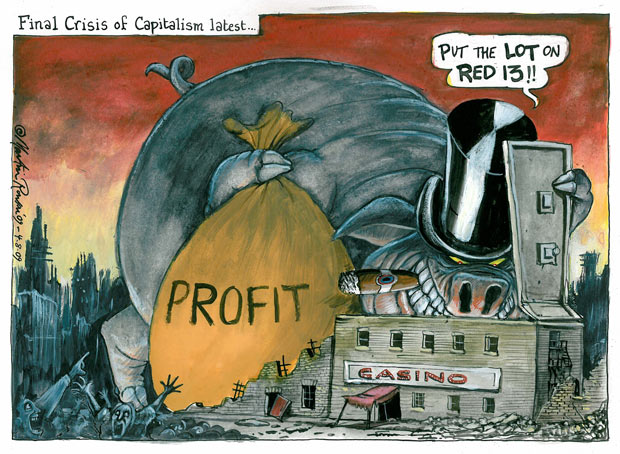

Keynes believed that the financial system — necessary for a vibrant market economy by channelling the entrepreneurs’ animal spirits into investments — is also so unstable and sensitive that it easily falls into crisis. The economy is permeated by genuinely uncertain processes and events that result in decision-making often based on incomplete knowledge. The estimates companies make about the future are usually mere guesses. Therefore, they are quickly and heavily influenced by shifts in economic sentiment. The market is thrown between optimism and pessimism. Faced with this uncertainty, people try to do what everyone else does. It is this herd instinct that contributes to the development of countries, which often resembles a by-product of casino activities.

Keynes believed that the financial system — necessary for a vibrant market economy by channelling the entrepreneurs’ animal spirits into investments — is also so unstable and sensitive that it easily falls into crisis. The economy is permeated by genuinely uncertain processes and events that result in decision-making often based on incomplete knowledge. The estimates companies make about the future are usually mere guesses. Therefore, they are quickly and heavily influenced by shifts in economic sentiment. The market is thrown between optimism and pessimism. Faced with this uncertainty, people try to do what everyone else does. It is this herd instinct that contributes to the development of countries, which often resembles a by-product of casino activities.

Speculation is to a large extent a question of forecasting the psychology of the market. Over time, Keynes argues, speculation has come to prevail at the expense of ‘enterprise.’ As financial markets grow and exert greater influence over the economy, the risk that speculation will predominate increases.

Speculators may do no harm as bubbles on a steady stream of enterprise. But the position is serious when enterprise becomes the bubble on a whirlpool of speculation. When the capital development of a country becomes a by-product of the activities of a casino, the job is likely to be ill-done.

Long-term expectations in an economy are largely governed by the confidence with which market participants make their future forecasts. This, in turn, is greatly influenced by empirical observations of the market and the psychology of business. The knowledge on which these future forecasts are based is ultimately very imperfect and leads to businessmen effectively engaging in a “mixed game of skill and chance.” The markets are governed by the convention that the present state of affairs will continue indefinitely unless we have specific reasons to expect a change. However, this convention is extremely fragile. The reason is, among other things, that the day-to-day fluctuations in the financial market tend to exercise an entirely excessive and, indeed, absurd influence on the market, and sudden changes in opinion give rise to waves of optimism and pessimism. Professional investors and speculators are largely preoccupied with anticipating changes in the conventional valuation basis a little ahead of the general public. This is the inescapable consequence of the very organization of the securities market, where the aim is to “outwit the crowd” and to pass the bad, or depreciating, half-crown to the next-door neighbour.

Keynes likened the financial market to a kind of parlour game in which “he is victor who says Snap neither too soon nor too late” — or to a sort of beauty contest where the prize goes to the participant whose choice is closest to the average estimation of all participants.

The consequence of this behaviour in the financial market is that investments are consistently made based on short-term considerations rather than long-term ones. Although this may be the most profitable approach, there are no clear grounds to suggest that it would be socially beneficial.

We should not conclude from this that everything depends on waves of irrational psychology. On the contrary, the state of long-term expectation is often steady, and, even when it is not, the other factors exert their compensating effects. We are merely reminding ourselves that human decisions affecting the future, whether personal or political or economic, cannot depend on strict mathematical expectation, since the basis for making such calculations does not exist; and that it is our innate urge to activity which makes the wheels go round, our rational selves choosing between the alternatives as best we are able, calculating where we can, but often falling back for our motive on whim or sentiment or chance.

An economy where speculation has gained significant prominence means that not only do crises and depressions become excessively severe, but also that economic prosperity becomes overly dependent on the political and social climate appealing to businessmen and speculators, instead of considering the needs and wants of ‘ordinary’ people.