It's not often I disagree with David Glasner. Or, for that matter, with Ralph Hawtrey. But I fear I have to take issue with both of them over competitive devaluation. "Bring it on", says David. No, please don't. It's a terrible idea.Hawtrey's pictorial explanation of why competitive devaluation is a good idea seems both charming and plausible: This competitive depreciation is an entirely imaginary danger. The benefit that a country derives from the depreciation of its currency is in the rise of its price level relative to its wage level, and does not depend on its competitive advantage. If other countries depreciate their currencies, its competitive advantage is destroyed, but the advantage of the price level remains both to it and to them. They in turn may carry the depreciation further, and gain a competitive advantage. But this race in depreciation reaches a natural limit when the fall in wages and in the prices of manufactured goods in terms of gold has gone so far in all the countries concerned as to regain the normal relation with the prices of primary products. When that occurs, the depression is over, and industry is everywhere remunerative and fully employed. Any countries that lag behind in the race will suffer from unemployment in their manufacturing industry.

Topics:

Frances Coppola considers the following as important: currency, Deflation, demand, Gold

This could be interesting, too:

NewDealdemocrat writes A further examination of the state of the economic tailwind

NewDealdemocrat writes A “Big Picture” summary of why a recession still looks likely, even if it hasn’t occurred yet

Frances Coppola writes The entire crypto ecosystem is a ponzi

Frances Coppola writes There’s no such thing as a safe stablecoin

It's not often I disagree with David Glasner. Or, for that matter, with Ralph Hawtrey. But I fear I have to take issue with both of them over competitive devaluation. "Bring it on", says David. No, please don't. It's a terrible idea.

Hawtrey's pictorial explanation of why competitive devaluation is a good idea seems both charming and plausible:

This competitive depreciation is an entirely imaginary danger. The benefit that a country derives from the depreciation of its currency is in the rise of its price level relative to its wage level, and does not depend on its competitive advantage. If other countries depreciate their currencies, its competitive advantage is destroyed, but the advantage of the price level remains both to it and to them. They in turn may carry the depreciation further, and gain a competitive advantage. But this race in depreciation reaches a natural limit when the fall in wages and in the prices of manufactured goods in terms of gold has gone so far in all the countries concerned as to regain the normal relation with the prices of primary products. When that occurs, the depression is over, and industry is everywhere remunerative and fully employed. Any countries that lag behind in the race will suffer from unemployment in their manufacturing industry. But the remedy lies in their own hands; all they have to do is to depreciate their currencies to the extent necessary to make the price level remunerative to their industry. Their tardiness does not benefit their competitors, once these latter are employed up to capacity. Indeed, if the countries that hang back are an important part of the world’s economic system, the result must be to leave the disparity of price levels partly uncorrected, with undesirable consequences to everybody. . . .

The highlight "in terms of gold" is mine, because it is the key to why Glasner is wrong. Hawtrey was right in his time, but his thinking does not apply now. We do not value today's currencies in terms of gold. We value them in terms of each other. And in such a system, competitive devaluation is by definition beggar-my-neighbour.The picture of an endless competition in currency depreciation is completely misleading. The race of depreciation is towards a definite goal; it is a competitive return to equilibrium. The situation is like that of a fishing fleet threatened with a storm; no harm is done if their return to a harbor of refuge is “competitive.” Let them race; the sooner they get there the better.

Let me explain. Hawtrey defines currency values in relation to gold, and advertises the benefit of devaluing in relation to gold. The fact that gold is the standard means there is no direct relationship between my currency and yours. I may devalue my currency relative to gold, but you do not have to: my currency will be worth less compared to yours, but if the medium of account is gold, this does not matter since yours will still be worth the same amount in terms of gold. Assuming that the world price of gold remains stable, devaluation therefore principally affects the DOMESTIC price level. As Hawtrey says, there may additionally be some external competitive advantage, but this is not the principal effect and it does not really matter if other countries also devalue. It is adjusting the relationship of domestic wages and prices in terms of gold that matters, since this eventually forces down the price of finished goods and therefore supports domestic demand.

Conversely, in a floating fiat currency system such as we have now, if I devalue my currency relative to yours, your currency rises relative to mine. There may be a domestic inflationary effect due to import price rises, but we do not value domestic wages or the prices of finished goods in terms of other currencies, so there can be no relative adjustment of wages to prices such as Hawtrey envisages. Devaluing the currency DOES NOT support domestic demand in a floating fiat currency system. It only rebalances the external position by making imports relatively more expensive and exports relatively cheaper.

This difference is crucial. In a gold standard system, devaluing the currency is a monetary adjustment to support domestic demand. In a floating fiat currency system, it is an external adjustment to improve competitiveness relative to other countries.

But so what, you say? What is wrong with countries competing on terms of trade?

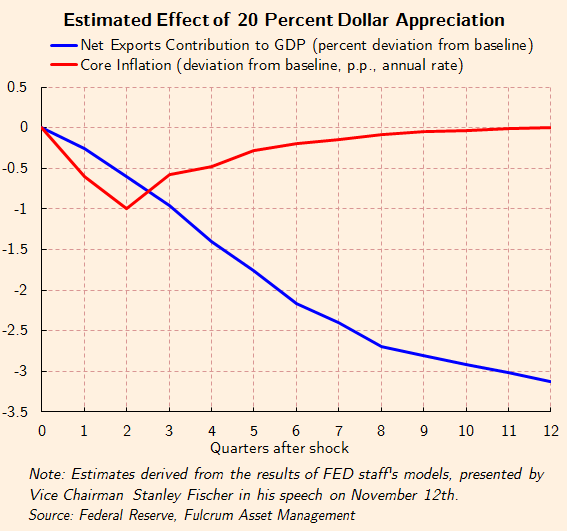

This graph, from Gavyn Davies in the FT, shows what happens to the "last fishing boat into harbour"(to use Hawtry's analogy):

(The 20% dollar appreciation has already happened, by the way: the US$ REER has risen that much in the last 18 months or so.)

Yes, that is a 1% deflationary shock and a 3% or more decline in the contribution of net exports to GDP. As Gavyn explains:

The negative impact of the rising dollar on the level of GDP, relative to the baseline, is surprisingly large and persistent, with a cumulative impact of around 3 percentage points after three years. About half of this effect arrives in the first four quarters after the dollar rise, with the rest coming later.

And he goes on to explain what the effect on (real) GDP would be:Importantly, the impact of the higher exchange rate does not reverse itself, at least in the time horizon of this simulation – it is a permanent hit to the level of GDP, assuming that monetary policy is not eased in the meantime.

Doesn't sound much like a "free lunch" to me.According to the model, the annual growth rate should have dropped by about 0.5-1.0 per cent by now, and this effect should increase somewhat further by the end of this year.

But of course this assumes that the US does not ease monetary policy further. Suppose that it does?

The hit to net exports shown on the above graph is caused by imports becoming relatively cheaper and exports relatively more expensive as other countries devalue. If the US eased monetary policy in order to devalue the dollar support nominal GDP, the relative prices of imports and exports would rebalance - to the detriment of those countries attempting to export to the US. They have three choices: they respond with further devaluation of their own currencies to support exports, they impose import tariffs to support their own balance of trade, or they accept the deflationary shock themselves. The first is the feared "competitive devaluation" - exporting deflation to other countries through manipulation of the currency; the second, if widely practised, results in a general contraction of global trade, to everyone's detriment; and you would think that no government would willingly accept the third. However, the Fed has permitted passive monetary tightening over the last eighteen months, and in December 2015 embarked on active monetary tightening in the form of interest rate rises. Davies questions the rationale for this, given the extraordinary rise in the dollar REER and the growing evidence that the US economy is weakening. I share his concern.

Hawtrey's "fishing fleet" analogy only applies when there is some kind of buffer that will absorb the deflationary shock. In his day, that was the gold price. These days, it is whichever country has the tightest monetary policy, which at the moment is the US. Though this could change once the Fed realises the world is once again casting the US in the role of consumer-of-last-resort - after all, this didn't end too well last time, did it? Central banks are passing deflation around the world like a hot potato.

Of course, if the world were to reintroduce some kind of common currency standard such as gold, we might be able to return to exchange rate targeting as a policy response. Alternatively, we could trade with Mars. But failing either of those, deliberately manipulating the exchange rate is destructive. In today's floating fiat currency system, there is no such thing as a "free lunch".

Related reading

The trade effect of negative interest rates

Japan's negative rates: the China connection

Let's all play QE - Pieria

Image is of Craster Harbour in Northumberland, UK. Photographed by me in April 2015.