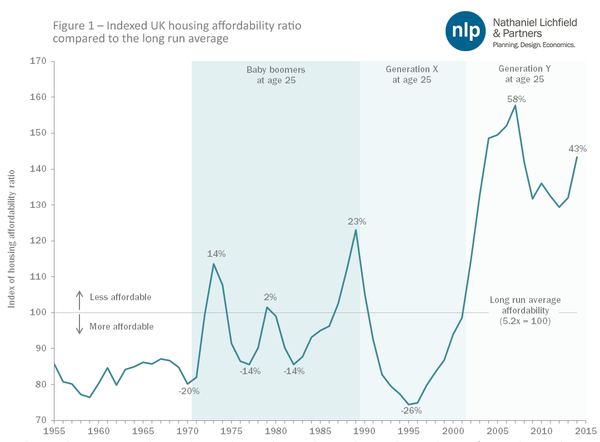

From Joe Sarling's blog comes this a lovely chart showing housing affordability by cohort since 1955: As can be seen, the current generation of young people - Generation Y - faces paying a far higher proportion of their incomes in mortgages or rent than any previous cohort. This does not, of course, take into account the considerable price difference between London and everywhere else: if London were excluded, I suspect their position would not look quite so dire. Nonetheless, this chart is distinctly worrying. Such a high proportion of income spent on housing costs is not remotely sustainable.But that is not what interested me about this chart. What is far more interesting is who really benefited from the increase in house prices since 1960. Contrary to popular opinion, it's not the baby boomers. It's the cohorts immediately before and immediately after them - Generation X, and (above all) the inter-war generation. Yes, those poor old people who grew up in the Depression and lived through World War II have benefited more from house price appreciation than anyone else. Considerably better, actually.To be sure, many of the inter-war generation did not own property - at least to start with.

Topics:

Frances Coppola considers the following as important: Financial Crisis, housing, Interest rates, mortgages

This could be interesting, too:

Nick Falvo writes Subsidized housing for francophone seniors in minority situations

NewDealdemocrat writes Declining Housing Construction

Nick Falvo writes Homelessness among older persons

Bill Haskell writes Q3 Update: Housing Delinquencies, Foreclosures and REO

As can be seen, the current generation of young people - Generation Y - faces paying a far higher proportion of their incomes in mortgages or rent than any previous cohort. This does not, of course, take into account the considerable price difference between London and everywhere else: if London were excluded, I suspect their position would not look quite so dire. Nonetheless, this chart is distinctly worrying. Such a high proportion of income spent on housing costs is not remotely sustainable.

But that is not what interested me about this chart. What is far more interesting is who really benefited from the increase in house prices since 1960. Contrary to popular opinion, it's not the baby boomers. It's the cohorts immediately before and immediately after them - Generation X, and (above all) the inter-war generation. Yes, those poor old people who grew up in the Depression and lived through World War II have benefited more from house price appreciation than anyone else. Considerably better, actually.

To be sure, many of the inter-war generation did not own property - at least to start with. The period from 1955-1970 was a period of enormous social housebuilding:

(chart from A Right To Build, Alastair Parvin)

The "cradle to grave" support that the post-war governments (of both colours) offered included a commitment to provide housing to whoever wanted it. So a whole generation grew up believing that they simply had to put down their name on a council waiting list and they would in due course get a house or a flat. To rent, of course. But they could rent it for life. And many of these houses and flats were substantial properties suitable for bringing up quite large families.

It's perhaps not widely known that - unlike the US - the UK did not have a baby boom in the 1950s. The UK's post-war baby boom was in two phases: those born immediately after the war (1946-50), and a second group born in Harold MacMillan's "you've never had it so good" period in the early 1960s. So Joe's chart is rather misleading, bringing together as it does two separate cohorts. I wonder exactly what he means by "baby boomers".

Anyway, the later cohort of "baby boomers" are the children of the inter-war generation. And I am one of them. The inter-war generation, encouraged by the easy availability of social housing and - for those who wanted to buy - low house prices, had large families. My father could afford the mortgage on a three-bedroom house with a garage, in the suburbs of London, on his modest salary as an insurance clerk. His wife, my mother, did not need to work. Which was just as well, as I am the eldest of four and my youngest brother is only five years younger than me. She had her work cut out.

Then came the inflation of the 1970s, and the first of several house price corrections, the Secondary Banking Crisis of 1973-5. The first group of baby boomers - those born after the war - were caught by this. House prices for the first cohort of baby boomers were significantly less affordable than they were for the inter-war generation. But they were nonetheless comfortable. My parents sold their three-bedroom semi for £14,500 in 1976, replacing it with a dilapidated six-bedroom Victorian house for the princely sum of £16,000. It needed work, of course, but the total expenditure on it was probably of the order of £20,000. It was still manageable on my father's salary alone.

But the 1980s destroyed all that.

There was another house price correction in the recession of the early 1980s. But this was followed by an enormous house price bubble. Fuelled by an overheating economy (the "Lawson boom") caused by over-easy monetary policy, and fiscal changes such as the ending of double mortgage interest rate tax relief for couples (signalled a year before it was implemented), house prices shot up. The inter-war generation who had rented social housing were allowed to buy their council properties through the Right to Buy programme. This also pushed up house prices, as the council properties were sold to their occupants at below market prices and then sold on by those occupants in order to turn a quick profit. Easy lending, too, helped feed the frenzy: 100% mortgages made their first appearance at that time, while mis-sold endowment policies enabled people to take on interest-only mortgages in the mistaken belief that an attached life insurance policy would pay the principal at maturity. Twenty years later, this came back to haunt them, as thousands of these policies proved to be worth far less than the mortgages they were supposed to pay off.

For the second cohort of baby boomers, together with those born in the 1950s, this house price boom was a disaster. Not only had the price of houses risen considerably, interest rates were sky-high. The Bank of England's base rate - to which most UK mortgages were tied - was in double digits for much of the 1980s, and by 1990 it was at nearly 15%. Of course older people were paying these rates too, but their mortgages were significantly smaller. The hit to their disposable income was far less. And social housing was no longer an option. The council houses had mostly been sold, and only those who met "need" criteria would qualify for social housing.

By 1988 I was earning more than my father, and I was single with no children. I wanted to buy my own property. But I could not afford a house like the one I grew up in, let alone the 6-bedroom Victorian house into which we had moved in 1976. So I left the suburbs of London, and moved somewhere cheaper. I thought that as my income rose, I would be able to return after say five years. That was twenty-eight years ago. Beckenham is still home, but - to misquote Robert Louis Stevenson - home is no more home to me. I know now that I will never return to the place where I was born.

I bought my first house in 1988, when I was 28 - the same age at which my father bought the house I grew up in. But buying in 1988 was disastrous. It was the peak of the boom. Lacking a deposit, I had bought my house with a 100% endowment mortgage. A year later, prices crashed. I spent the next seven years in negative equity, unable to move and paying huge amounts in interest on a mortgage whose principal did not reduce (because the tied endowment policy meant it was interest-only).

Joe's chart shows how bad the 1990s housing crash was. It wiped out the net worth of the 1960s baby boomers who bought property in the late 1980s. Because so many of us were in negative equity, we ended up in a worse wealth position than those ten years younger than us - Generation X.

Generation X entered the market when housing affordability was at levels not seen since the 1950s. They bought at the bottom, and then benefited from the record-breaking rise in house prices that peaked in 2006. And though they lost some value in the 2007-8 crash, the house price collapse was nowhere near as deep as that in the 1990s. Generation X have fared well from rising house prices.

But the inter-war generation have fared the best of all. Yes, they lived through the inflation of the 1970s and the high interest rates of the 1980s. But their mortgages were largely paid off by the 1990s, so they were never in negative equity. And despite the crashes of the 1970s, 1990 and 2007-8, overall the period from 1955-2016 has seen a simply enormous rise in house prices. Those who owned property throughout that period have done very well indeed. In 1999, my parents sold the aforementioned six-bedroom Victorian house in Beckenham for £200,000, and bought a three-bedroom bungalow outside London for cash. That bungalow too is now worth considerably more than when they bought it. Even now, the inter-war generation continue to benefit from rising house prices.

So please don't blame the "baby boomers" for the house price appreciation that has made property unaffordable for large numbers of today's young people, They are neither the cause of it nor the principal beneficiaries.