By Steve Roth (via Asymptosis) Wealth and the National Accounts: Response to Matthew Klein I’m both abashed and delighted that the truly stand-out econ writer Matthew Klein has offered wonderfully fulsome praise of one of my pieces, Why Economists Don’t Know How to Think about Wealth, and some very interesting discussion as well. Some responses here. Please excuse me if I repeat some of the points from the first article. >His key point is that changes in net worth caused by asset prices fluctuations are just as important as standard measures of income and saving. That’s important, but there are really three key points I’d really like to come through: 1. Wealth matters. Net worth and total assets. Those are absent from the Flow of Funds matrix, because

Topics:

Dan Crawford considers the following as important: Featured Stories, Taxes/regulation, US/Global Economics

This could be interesting, too:

Ken Melvin writes A Developed Taste

Joel Eissenberg writes How Tesla makes money

Angry Bear writes True pricing: effects on competition

Angry Bear writes The paradox of economic competition

by Steve Roth (via Asymptosis)

Wealth and the National Accounts: Response to Matthew Klein

I’m both abashed and delighted that the truly stand-out econ writer Matthew Klein has offered wonderfully fulsome praise of one of my pieces, Why Economists Don’t Know How to Think about Wealth, and some very interesting discussion as well. Some responses here. Please excuse me if I repeat some of the points from the first article.

>His key point is that changes in net worth caused by asset prices fluctuations are just as important as standard measures of income and saving.

That’s important, but there are really three key points I’d really like to come through:

1. Wealth matters. Net worth and total assets. Those are absent from the Flow of Funds matrix, because it ignores: A. Nonfinancial assets — the (L)evels tables aren’t balance sheets — and B. Holding gains. Yes: changes in wealth measures also matter a lot (see below), and they’re of course also invisible and largely unexplained in the FFA matrix.

2. Accounting statements are economic models, based on deeply-embedded assumptions that are largely invisible except to accounting-theory adepts. The FFAs’ closed-loop construct depicts, promulgates, and validates the whole factors-of-production worldview (each according to its contribution…) which underpins travesties like Greg Mankiw’s “just deserts” claptrap. See in particular national-accounting-sage Robert Hall’s discussion of the accounts’ implicit “zero-rent economy.”

3. The dumpster fire (@noahpinion) of terminology that economists rely on to communicate — and really to think (together) — is (or should be) rigorously defined based on accounting identities. But that requires deeply understanding #2 above: what those measures and identities mean. To repeat: accounting classes don’t even count as electives for econ degrees at Harvard and U Chicago. (Really, the situation is more like the sub-basement of Fukushima Three. One word: “saving.” Many economists vaguely think that more individual saving results in some larger stock of monetary “savings.” Sheesh.)

>Roth’s presentation…is not new. Alan Greenspan wrote about these ideas back in the 1950s

Johnny-come-lately. Haig-Simons, who I refer to repeatedly, bruited their comprehensive accounting definition of income in the 20s and 30s. (Dead-cat bounce. I’m thinking the rich hatethis idea. The political implications of fully revealing wealth and wealth accumulation could be…revolutionary?)

Wikipedia informs me that a German legal scholar named Georg von Schanz was on it somewhat earlier. (Modern Money Network, are you listening?)

>Roth ends up downplaying the importance of the liability side of the balance sheet.

Perhaps. At least three reasons:

1.The FFA matrix does an excellent job of accounting for (inevitably “financial”) liabilities. Nothing to complain about there. That’s where the IMAs get most or all of their liability accounting from. And economists have made very good use of that data.

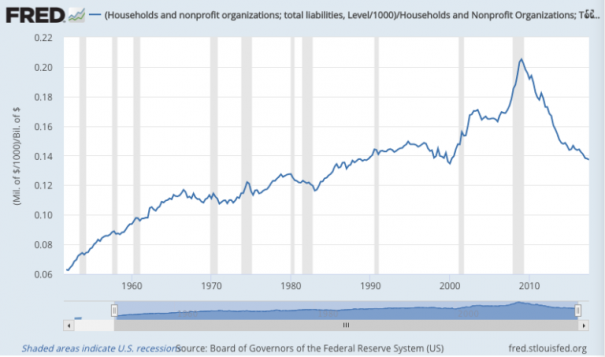

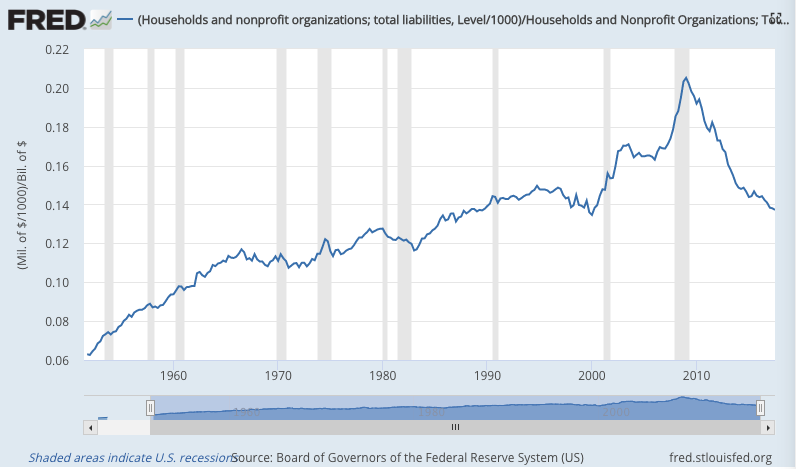

2. Looking at households as the “buck stops here” balance sheet, liabilities are surprisingly (to me) small percentage of assets. Yes, a long secular trend with one big spike (not much for sample size…). Click for Fred.

3. For the economic import of (change in) assets versus liabilites, I’ll just point to one economic factoid which I find darned significant:

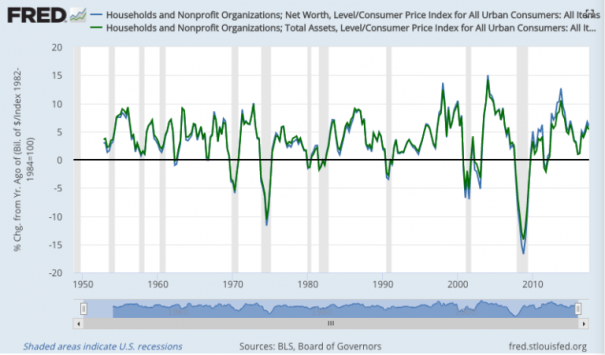

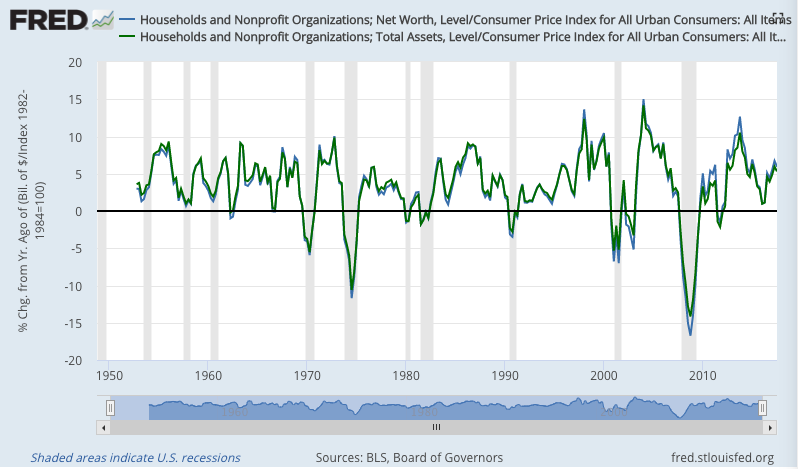

Post-1960s (post Bretton-Woods?), every time you see year-over-year decline in real household net worth or assets, you’re just into or about to be in a recession. (There are two bare false positives, just after the ’99 and ’08-’09 market dives; they look to me like blowback, residual turbulence, if that suffices as cogent economic terminology…)

Notice: The two measures are equally predictive; including liabilities (in net worth) adds no predictive power. These two measures move closely together. This especially makes sense for declines; asset markets dive, while liabilities are much more sticky downward. (They tend to climb together over time.)

So yeah, I’m with Roger Farmer about stock-market declines “Granger-causing” recessions, though 1. I cringe at that faux-statistical usage, and 2. at least for the GFC, I’d say the real-estate crash caused the stock-market crash. In any case, overall, it sure looks to me like wealth (asset) declines (proximate?) cause recessions. I’d say high debt levels amplify the effects when that does happen.

So yeah of course, net worth is not some kind of tell-all economic measure. You gotta deconstruct it. But it’s a bloody-well-necessary measure that economists (and national accountants) have largely ignored, like forever.

>defining “saving” as the “change in net worth”, as Roth does, is that this obscures as much as it clarifies

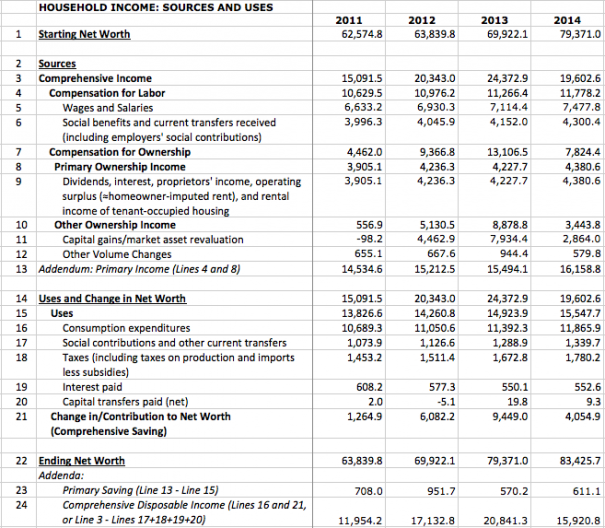

Note that I use a particular term for that, Comprehensive Saving, while leaving what I call Primary Saving (largely) intact. (The IMAs’ measure of primary income hence saving is after “Uses of property income (interest paid)” are deducted, which seems crazy (and politically pernicious) to me. I’ve moved it from it’s sort-of-hidden position in Sources, to appear explicitly in Uses, so my Primary Income and Primary Saving measures are a bit higher than the IMAs’.)

Now it’s true that I relegate Primary Saving to an addendum, favoring Comprehensive Saving as the more important measure. This imparts how deeply rhetorical all accounting presentations are. But I think this privileging makes sense give the relative magnitudes we see. (Net Lending + Capital Formation here is traditional primary “saving”).

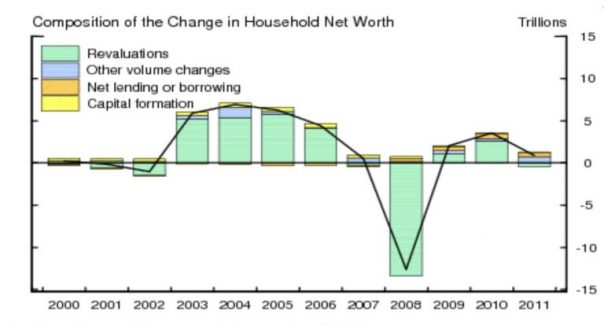

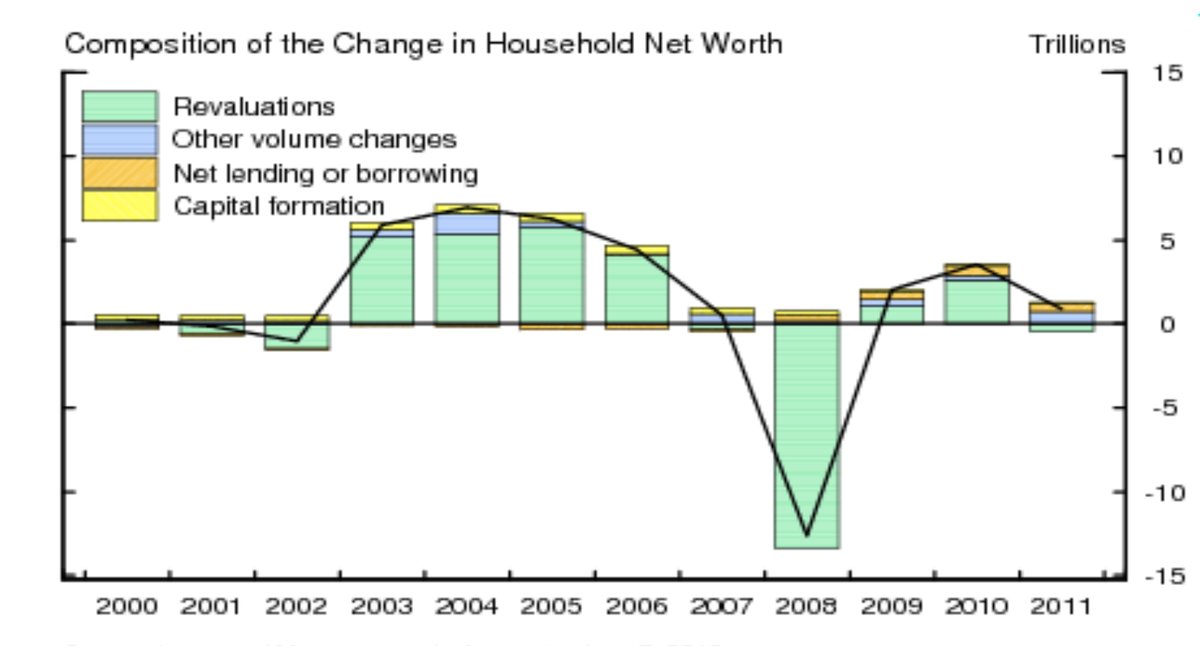

This is J.W. Mason’s recent graph, which I was delighted to see, showing the same measures (the IMAs’ ∆NW decomposition) that I’ve also graphed in the past.

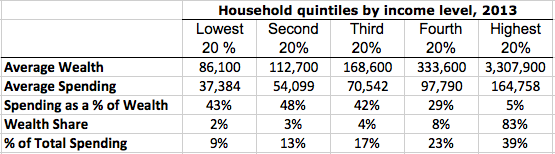

>asset price appreciation generally leads to proportionally tiny increases in spending.

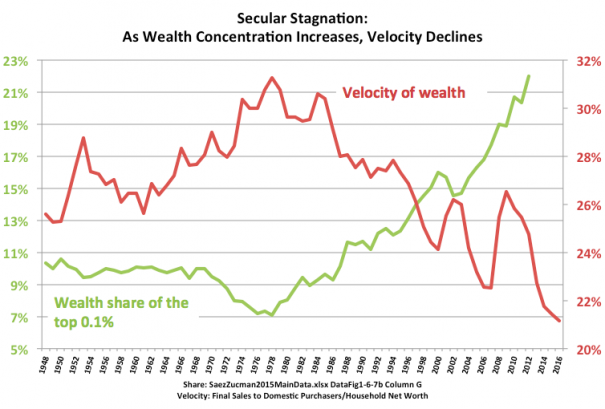

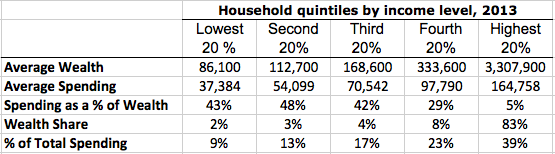

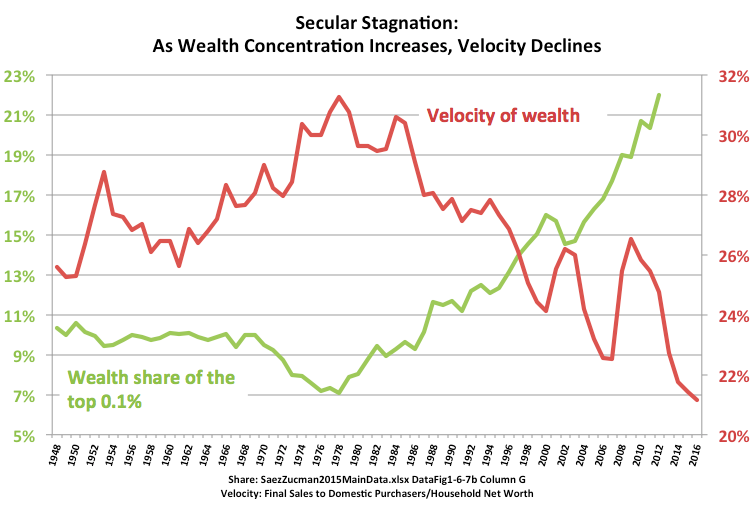

The linked study, like others of its kind, in my opinion gives too much weight to marginal propensities, based on one-time changes. So I question how good a guide they are to determining economic reaction functions. This is too much of a subject to address here, so I’ll only suggest that more straightforward, long-term propensity-to-consume measures by wealth/income classes might be more illuminating. Also velocity of wealth. (I’m a monetarist! As long as “money” means “wealth”…)

Whether or not you consider these figures illuminating, they are the kind of figures you can derive from a complete accounting construct that tallies total assets and net worth. Note that both are also dependent on data from Zucman/Saez/Pikkety’s magisterial Distributional National Accounts (DINAs). What I’d really like to see is Distributional IMAs (DIMAs). I corresponded with Gabriel Zucman on this a bit; he’s given me permission to quote him:

You are correct that there can be pure asset valuation effects in the long run (i.e., capital gains in excess of those mechanically caused by retained earnings). These pure valuation effects are not part of national income, hence not included in our measure of income and our distributional series. However, they could be included down the road by computing income as delta wealth + consumption (i.e., Haig-Simon income). We have wealth in our database so we’re not far from being able to do this.

To conclude on a decidedly accounting-dweeby note, here’s the key accounting identity for Haig-Simons (which I call Comprehensive) Income:

∆ Net Worth + Consumption = Primary (traditional) Income + Holding Gains (+ Other Changes in Volume)

Subtract taxes, and you’ve got Comprehensive Disposable Income. Subtract Consumption, and you’ve got Comprehensive Saving. Equals…change in Net Worth.

Accounting identi-tists, have fun!

(For those who prefer this kind of thing in slide-deck form, here’s a PDF of my presentation from the recent Modern Monetary Theory conference.)