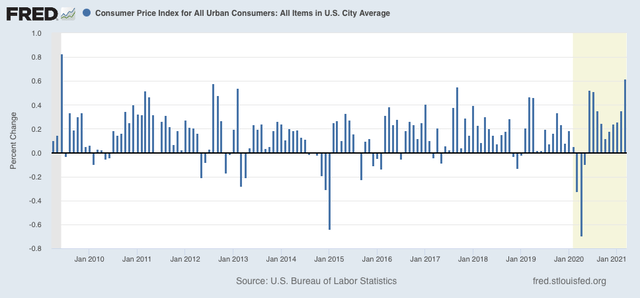

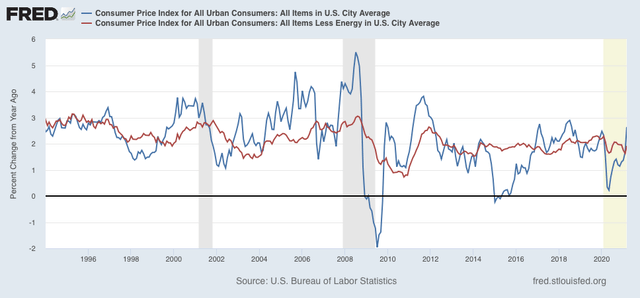

Monthly consumer inflation rate increases by most in 10 years; real wages decline, but real aggregate wages increase – by New Deal democratSeasonally adjusted consumer prices rose 0.6% in March. This was the biggest single month gain since June 2009, coming out of the Great Recession: Leaving aside the pandemic, since the 1980s recessions have only happened when CPI less energy costs (red) had risen to close to or over 3%/year, usually driven by increases in the price of oil by more than 40% YoY. Even with this month’s spike, YoY inflation ex-energy is only up 1.9%: Because in the first few months of the pandemic during the lockdowns there was a spurt of deflation as shown above in the first graph, in the below graph I’ve normed

Topics:

NewDealdemocrat considers the following as important: Real Wages, US/Global Economics

This could be interesting, too:

Joel Eissenberg writes How Tesla makes money

Angry Bear writes True pricing: effects on competition

Angry Bear writes The paradox of economic competition

Angry Bear writes USMAC Exempts Certain Items Coming out of Mexico and Canada

Monthly consumer inflation rate increases by most in 10 years; real wages decline, but real aggregate wages increase

– by New Deal democratSeasonally adjusted consumer prices rose 0.6% in March. This was the biggest single month gain since June 2009, coming out of the Great Recession:

Leaving aside the pandemic, since the 1980s recessions have only happened when CPI less energy costs (red) had risen to close to or over 3%/year, usually driven by increases in the price of oil by more than 40% YoY. Even with this month’s spike, YoY inflation ex-energy is only up 1.9%:

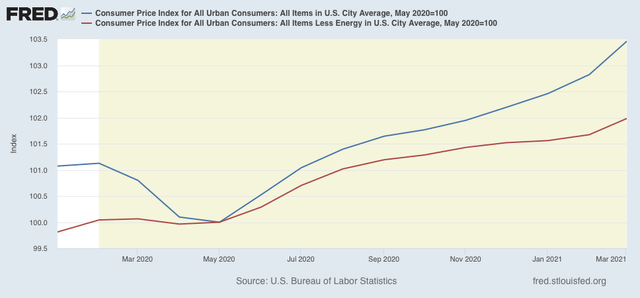

Because in the first few months of the pandemic during the lockdowns there was a spurt of deflation as shown above in the first graph, in the below graph I’ve normed the values to 100 as of May of last year. In the 9 months since, total inflation has been up 3.5% (for a 4.7% annual rate), while inflation ex-energy has risen 2.0%, (for a 2.7% annual rate):

This is still not enough to be of concern on a transient basis.

Now let’s take a look at how inflation has affected real wages.

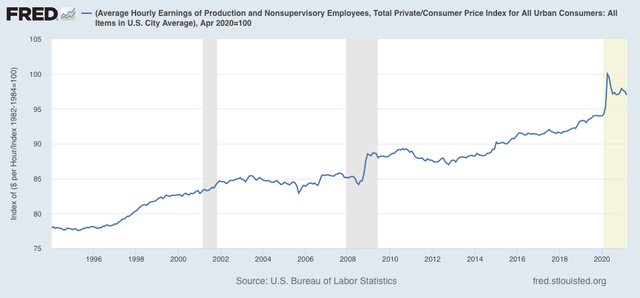

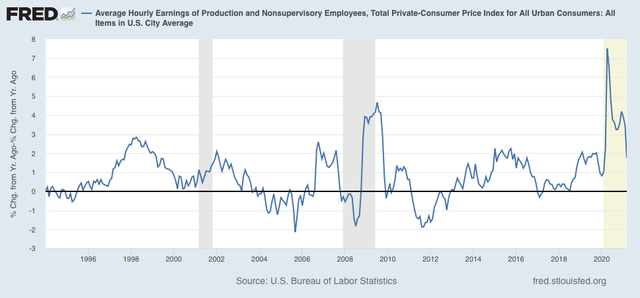

Because wages are “stickier” than prices, typically as recessions beat down prices (or at least price increases), in real terms wages rise, either during or just after a recession. That was the case for the coronavirus recession as well. As prices increase with renewed demand, and employers are able to add workers from the larger pool of the unemployed and underemployed, real wages decelerate and even decline.

That was the case for March. Real wages declined -0.5%, and are -3.1% off their all-time high set last April:

They are still 0.9% above their previous 1973 peak

.

As more low-wage employees in service industries like dining and entertainment are called back to work, the YoY% change in real wages has decreased from over 7% last April to 1.9% in March:

A further decline in real wages is quite likely. As a result, YoY real wage increases have declined from over 5% last I suspect we will see an actual YoY decline in real wages by the end of this year.

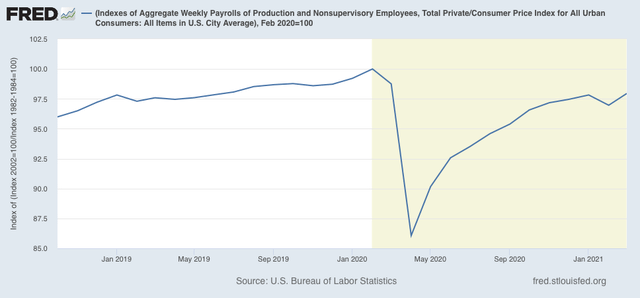

A bright spot is that real *aggregate* payrolls for nonsupervisory workers did increase:

These are now only -2.1% below their pre-pandemic peak, and equivalent to where they were in July 2019. If vaccinations succeed in controlling the pandemic, it is quite likely that these make a new all-time high by the end of the year as well.