A comment on housing, inflation, and Fed policy (and a side comment on spending) No big economic news today, and as usual little State reporting on COVID over the weekend, so let me make a couple of points. As an initial note, the big report I will be paying attention to this week is personal spending and income, which will be reported on Thursday. As I’ve noted several times recently, the goods-producing side of the economy has been fading somewhat. And earlier this month, we got an awful retail sales report (which we average about once every year). Personal spending is the flip side of retail sales. And what’s been happening there is a bifurcation between spending on goods vs. spending on services. Here’s a graph of each, normed to 100

Topics:

NewDealdemocrat considers the following as important: Fed Policy, housing and domestic demand, inflation expectation hypothesis, New Deal Democrat, politics, US EConomics

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Skidelsky writes Lord Skidelsky to ask His Majesty’s Government what is their policy with regard to the Ukraine war following the new policy of the government of the United States of America.

NewDealdemocrat writes JOLTS revisions from Yesterday’s Report

Joel Eissenberg writes No Invading Allies Act

Ken Melvin writes A Developed Taste

A comment on housing, inflation, and Fed policy (and a side comment on spending)

No big economic news today, and as usual little State reporting on COVID over the weekend, so let me make a couple of points.

As an initial note, the big report I will be paying attention to this week is personal spending and income, which will be reported on Thursday.

As I’ve noted several times recently, the goods-producing side of the economy has been fading somewhat. And earlier this month, we got an awful retail sales report (which we average about once every year).

Personal spending is the flip side of retail sales. And what’s been happening there is a bifurcation between spending on goods vs. spending on services. Here’s a graph of each, normed to 100 as of right before the pandemic:

There was a huge increase in spending on goods, especially in last spring’s stimulus spending spree. But that was while a lot of people were avoiding social events and were ordering stuff from home. While that has faded in the past year, spending on services has motored right ahead, and is presently still up about 6% YoY – which in the long term is a *very* healthy rate.

Which means that the signal from a fading goods-producing sector – normally a reliable leading indicator – may be overstated this time around.

We’ll get a further read on that Thursday.

Now, on to my main topic: inflation.

Prof. Paul Krugman continues to tweet that inflation may be taking care of itself, and the Fed shouldn’t hit the brakes too hard, e.g., in this long twitter thread:

https://mobile.twitter.com/paulkrugman/status/1541039031525457923

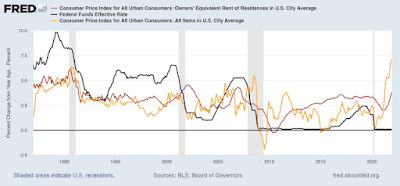

I would be very cautious about this. That’s because, to recapitulate, 1/3rd of the entire CPI reading is housing, and housing prices have been on a tear. That gets reflected, with a 12 to 18 month lag, in “owner’s equivalent rent” (OER), which is currently at a 30 year high (gold in the graph below, vs. overall CPI, red):

Inflation normally declines before OER peaks, but precisely *because* the Fed slams on the brakes (black in the graph above).

Well, house prices are still up (awaiting tomorrow’s updates) about 16% YoY. That is going to continue to feed into OER for the next 12 months at least.

In other words, the only reason inflation declines in the next 12 months is if the non-housing 2/3’s of the number slows down drastically. I’m skeptical of that happening if the Fed retreats towards the sidelines.

That being said, the Fed should as a matter of discipline differentiate between supply-driven inflation, especially of durable goods, vs. demand-driven inflation. That’s because, if there is a supply bottleneck, that bottleneck isn’t going to magically disappear by cutting down demand. All it is going to do is create more pent-up demand, and unleash more inflation in that good once interest rates are lowered.

This is particularly true of housing. To the extent housing inflation is driven by a shortage of construction materials, building even less housing to keep a lid on prices just means even more of a shortage of housing, and more demand once the Fed releases the brakes. In other words, if there’s a shortage of supply of a durable good, the Fed ought to accept higher inflation rather than bring on a needless recession which won’t cure that shortage anyway.