American capitalism has an everpresent desire for increased profits. Over the course of history, corporations had increased profits largely due to increased population growth. As we have seen from new data coming from the 2020 Census, population growth is beginning to stabilize and flatten, yet corporations are still expected to perform regardless of market conditions, and if population growth is no longer the cosmic funnel of operating revenues, extracting rents like feudal lords is the next best thing. I had stated in earlier posts that the Sherman Act wouldn’t be necessary, as the smaller producers could be that necessary competition, after much consideration and research amongst the community, there just isn’t time. The independent processors

Topics:

Michael Smith considers the following as important: Hot Topics, Meat Monopoly, Michael Smith, Taxes/regulation, US/Global Economics, USDA

This could be interesting, too:

NewDealdemocrat writes JOLTS revisions from Yesterday’s Report

Joel Eissenberg writes No Invading Allies Act

Joel Eissenberg writes How Tesla makes money

NewDealdemocrat writes January JOLTS report: monthly increases, but significant downward revisions to 2024

American capitalism has an everpresent desire for increased profits. Over the course of history, corporations had increased profits largely due to increased population growth. As we have seen from new data coming from the 2020 Census, population growth is beginning to stabilize and flatten, yet corporations are still expected to perform regardless of market conditions, and if population growth is no longer the cosmic funnel of operating revenues, extracting rents like feudal lords is the next best thing.

I had stated in earlier posts that the Sherman Act wouldn’t be necessary, as the smaller producers could be that necessary competition, after much consideration and research amongst the community, there just isn’t time. The independent processors are disorganized, and the governmental approach is unfortunately, the same as it ever was. In reality, the USDA is part of how we got here in the first place. The FTC has allowed mergers and acquisitions and the USDA has removed or turned a blind eye from providing remedy, effectively allowing the food monopoly to exist in what economists from the Reagan era describe as “efficiency” to provide the “best price” for the consumer. What about the producer? The current state of affairs has allowed the middle man to squeeze the producer and the consumer alike.

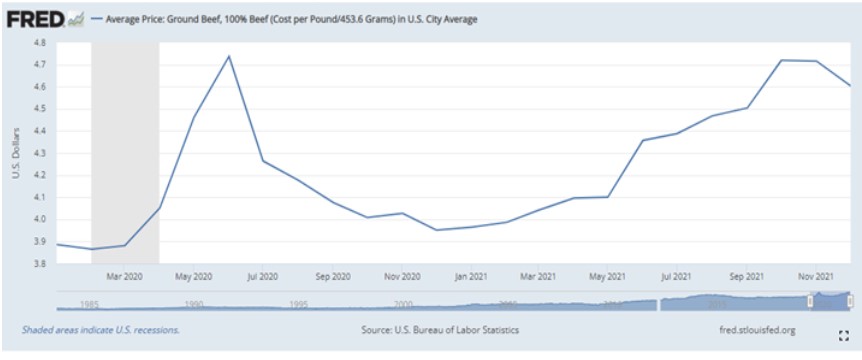

A monopoly can be easily seen when looking at the strata of data among a specific industry. Two things to look for, a)increase in prices from a small oligopoly of companies operating in the same space, with only a few competitors, b)input prices decline from primary vendors. As the price of beef at the retail counter goes up in Q4 2021:

(Average price of ground beef, average, USDA.gov)

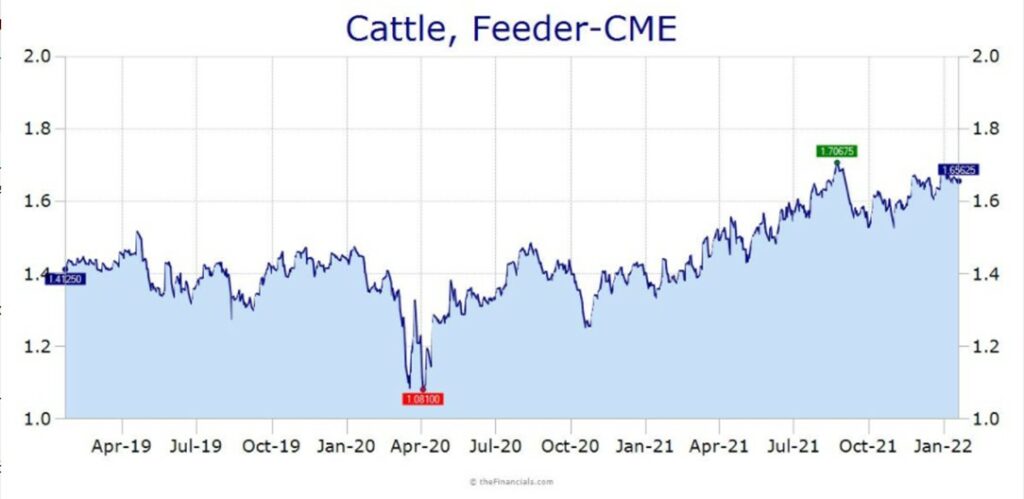

The input prices from the cattle auctions either stay stable, or in this case, decline:

(Feeder cattle, www.thefinancials.com)

When we break these two graphs down, the USDA reported an average of $4.60 per pound of ground beef, much higher than recent trends. Half of a beve (beef cow) is usually ground, or around 220 pounds on average per carcass. When we compare that to the declining and then stabilizing price per 100 average of $1.60 per pound during the same period at the cattle auction, the two do not move in tendem. Now, on hoof weight, or live weight of 600 pounds will net the farmer $960, but all in, they might have paid $500 for the calf, and potentially a couple hundred dollars on milk if it was a bottle calf and/or feed, hay, and vet bills. Put another way, per the Sterling Beef Profit Tacker 2021, who do the arduous job of tracking the costs and revenues of the beef industry, have published their assessment of future margins.

Week ending November 26th, 2021, Estimated 2022 margins:

Cow/calf ($/cow) – $142.00

Feedlot ($/cow) – 39.50

Packer ($/cow) – $610.00

Definitions – cow/calf operations are the ones birthing the cows, raising, weening, and then selling them for finishing in either a stockyard (grass fed) or feedlot (finisher who uses silage feed), and then packer/processor are Tyson Foods, Cargill, etc.

Now this is significantly better for producers than 2019 and 2020, where the cost per head was $85.97, and 78.86 per head, respectively. But during those times, in 2019, packers made $214.39 and $464.24 in 2020. Why the jump? If my grandfather were here, he’d say something akin to “frog in a fryin’ pan”. Yes, we have had a global pandemic, now going into it’s third year, and supply chains have been stressed, causing higher shipping and labor prices. Aside from those, the input costs have either stayed relatively the same, or only modestly inclined. This leads me to the Department of Labor:

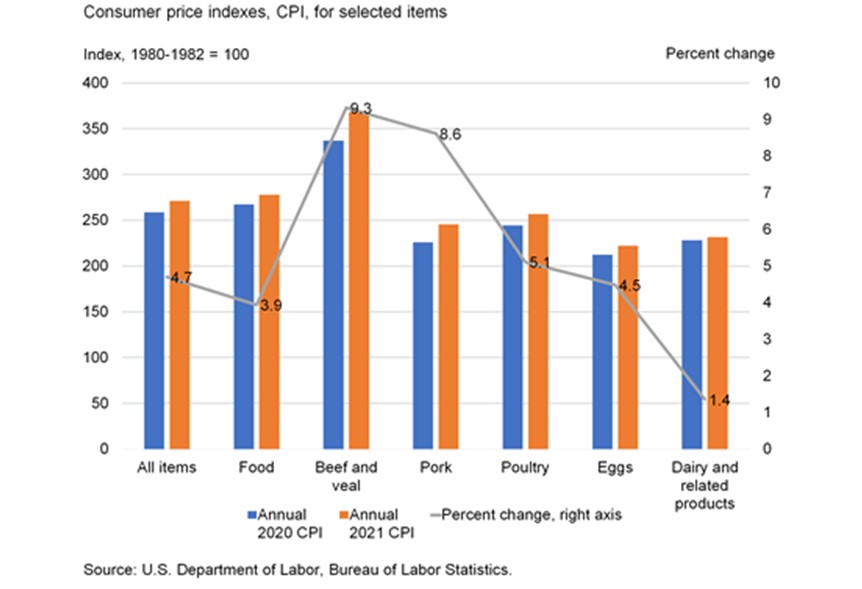

The annual CPI for all items rose 4.7% year over year, food, 3.9%, poultry is within range, and yet pork is up 8.5% and beef even higher at a staggering 9.3%?

If we were to believe the supply chain narrative, labor shortage narrative, poultry, dairy, food, and All Items would be rather consistent across the board. But they are not. Producer Prices do effect consumer prices, correlated per FRED data:

Yes, inflation is increasing both PPI and, CPI, but they relatively move in tandem. The beef packers have an exponential rate of increase that is out of bounds with the overall ecnomic linear inflation progression.

Secondary Cause & Effect

Going into 2022, the pandemic now offering new variants that make life, supply chains, and labor more difficult, inflation seems to continue, as the Fed has predicted to continue into this year, with a core PCE inflation median forecast of 2.7%, down from 4.4% for 2021, which includes 3 Fed rate hikes to get there.

Farm and Ranch operations have difficulty surviving extreme inflation events. Feeding the family takes more money, feeding the animals, even more so. Silage competes with ethanol and plastics, vegetable oil, and even oil & gas. The more consumers spend on things, the price of those inputs goes up. Take in consideration that corn is used both to make plastics and also gasoline additives. Crude oil prices effect the fertilizer market. If inflation sets in, everything costs more. Same can be said from a borrowing perspective. As the Fed raises rates, the cost of borrowing increases. Tens of billions of dollars in loans are made each year to float the agricultural producers by term loans to pay for land, equipment, and even their houses, and then operating loans that help with the annual planting, or purchasing of animals. Much like the general public, the farmers get pinched both ways. Annual operating loans, however, are nothing like a standard 30 year mortgage.

Knowing this, I recently threw out a question to #AgTwitter: How many farmers and ranchers are a)retiring b)getting out, or c)doubling down? The responses I got were all over the place, as one should expect from Twitter. A few anecdotal report from guys like “Vernon” who sold the whole herd and entered retirement a bit ahead of schedule, @dustdevil313 had seen ads for “complete dispersions […] used to seeing a lot of age dispersions and usually smaller bunches of older guys, but these have been big bunches of long time operators.” No land sales, which is a good sign.

Brandi Buzzard Frobase, Director of Communications of the Red Angus Association, whom I have quoted here before, hasn’t seen anything other than the normal dispersions, but also states that she works for a breed association, and “is probably skewed”.

Jessica Benson, a broadcaster for American Ag Network and podcaster noted on her families’ multi-generational farm in Minnesota that “(we are chosing to) supplement income, but I know things are still very difficult and emotionally taxing.” She also brings up a subject that I see around in my and adjacent counties in Central Texas, as an overall theme in the industry, “[…]we are maybe in that stage of trying to get creative, or maybe getting out, due to my parents wanting to retire and not enough help avaliable.”

This hints at the larger slow-moving glacier, again, as the farming and ranching population continues to age, there are less and less being replaced. What used to be 1.2 million cattle operations has now shrunk to 880,000, and declining more each year as the ranchers hang up the reigns and the children face the huge costs to continue operations. Getting into the ranching business with no land or family in the business is akin to swimming in a pool filled with peanut butter. These exits do not create opportunities that we would imagine, but allow for two things:

- Smaller amount of producers, smaller supply, demand not elastic = higher costs, or

- Monopolists controlling the market buy, or by proxy, productive farmland, further integrating, see “poultry farming”

The second reason is why trade organizations are calling for the government to break up with the Big Four packers. Opposition is nothing new, as The Counter reported in 2019, “A new lawsuit accuses the ‘Big Four’ of conspiring to fix cattle prices”. In reality, both reasons are good incentives to break up the meat packing industry into smaller regional outfits that are not allowed predatory contractual practices and cannot shut the door on the small time ranchers. Couple this with common sense USDA programs that dissolve some of the barriers to entry, support the young, beginning farmers, offer a lifeline to custom processors and there might be a reversal of fortunes for the future of meat and food in general.