Lloyd answers the question about how Americans will be getting their food from fast food establishments in the future. Innovative but does little for the environment and also for people’s health setting aside the argument of fast food not being necessarily healthy. To catch the rest of Lloyd’s article, click on the Carbon Upfront link. In the future, everything will be a drive-through, Carbon Upfront, Lloyd Alter Hamburger’s History The first practical meat grinder was displayed at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition of 1876, and the first Hamburg steak was served there on a plate and eaten with a knife and fork. According to Andrew F. Smith in his book Hamburger: A Global History, it became popular fast. “Ground meat was cheap, ideal

Topics:

Angry Bear considers the following as important: Carbon Upfront, climate change, Education, Lloyd Alter

This could be interesting, too:

Joel Eissenberg writes How Tesla makes money

Joel Eissenberg writes The Trump/Vance Administration seeks academic mediocrity

Bill Haskell writes Study Shows Workers Fleeing States With Abortion Bans

Angry Bear writes The Impact of Debt Interest Payments

Lloyd answers the question about how Americans will be getting their food from fast food establishments in the future. Innovative but does little for the environment and also for people’s health setting aside the argument of fast food not being necessarily healthy. To catch the rest of Lloyd’s article, click on the Carbon Upfront link.

In the future, everything will be a drive-through, Carbon Upfront, Lloyd Alter

Hamburger’s History

The first practical meat grinder was displayed at the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition of 1876, and the first Hamburg steak was served there on a plate and eaten with a knife and fork. According to Andrew F. Smith in his book Hamburger: A Global History, it became popular fast.

“Ground meat was cheap, ideal to sell to the working classes. By adding even cheaper fillers, such as gristle, skin and excess fat, the butcher could enhance his already substantial profit.”

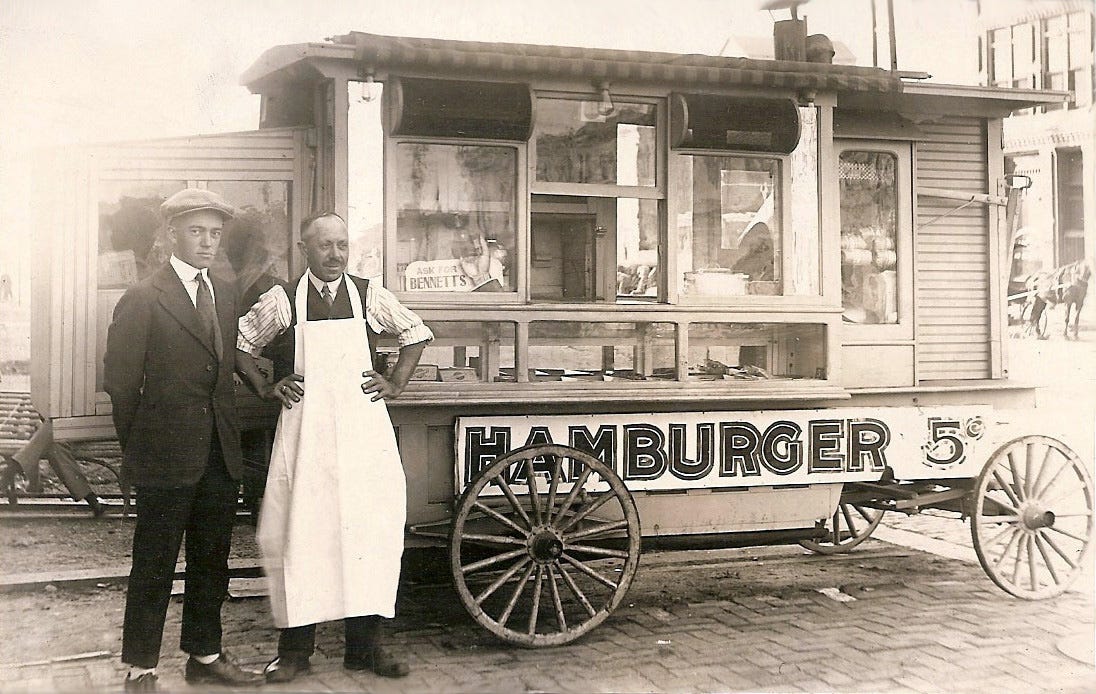

The Hamburg steak became a Hamburg sandwich. When workers needed lunch at the new factories and mills, and lunch wagons and carts opened to serve them. Smith notes:

“Because many customers ate their food standing up, placing the beef patty in a bun made sense. Who was the first lunch wagon proprietor to sell the Hamburg steak between two pieces of bread is unknown, but by the 1890s, it had already become an American classic.”

Pure food activists complained:

”The hamburger habit is just about as safe as walking in an orchard while the arsenic spray is being applied, and about as safe as getting your meat out of a garbage can standing in the hot sun. For, beyond all doubt the garbage can is where the chopped meat sold by most butchers belongs, as well as a large percentage of all the hamburger that goes into sandwiches.”

Soon, the street vendors and carts selling burgers were pushed off the road by the car. Vendors moved indoors to cafés and diners, many of whom continued to sell burgers of dubious quality.

In 1916, Walt Anderson tried to change the hamburger for the better. He opened a shop with a window where customers could see him grind his own beef and make fresh patties in front of their eyes. He then partnered with an investor to open the White Castle, with white tile interiors representing purity and cleanliness. It was a huge success. They opened in urban areas near bus and trolley stops and close to large factories.

Things changed after the Second World War with the boom in car ownership. The inner city hamburger chains didn’t have parking, and everyone was moving to the suburbs, a wide-open market for new chains with new ideas. The McDonald brothers applied an assembly-line model to their California restaurant to deal with staff shortages, as well as switching to disposable cutlery and plates. They outsourced much of the work to their customers. Smith writes:

“This assembly-line system provided customers with fast, reliable and inexpensive food; in return, the McDonald brothers expected their customers to queue, pick up their own food, eat quickly, clean up their own rubbish and leave without delay, thereby making room for others.”

This was the start of the extravagantly wasteful linear food system we have today. The McDonalds refused to provide indoor seating. There might be a few picnic tables, but customers were expected to eat in their cars.

Everyone showed up at their window to copy it; that’s how we got Burger King, which started as a Florida knockoff. A man named Glen Bell went Mexican and called it Taco Bell. Today, much of the world’s food is served on the McDonald’s model.

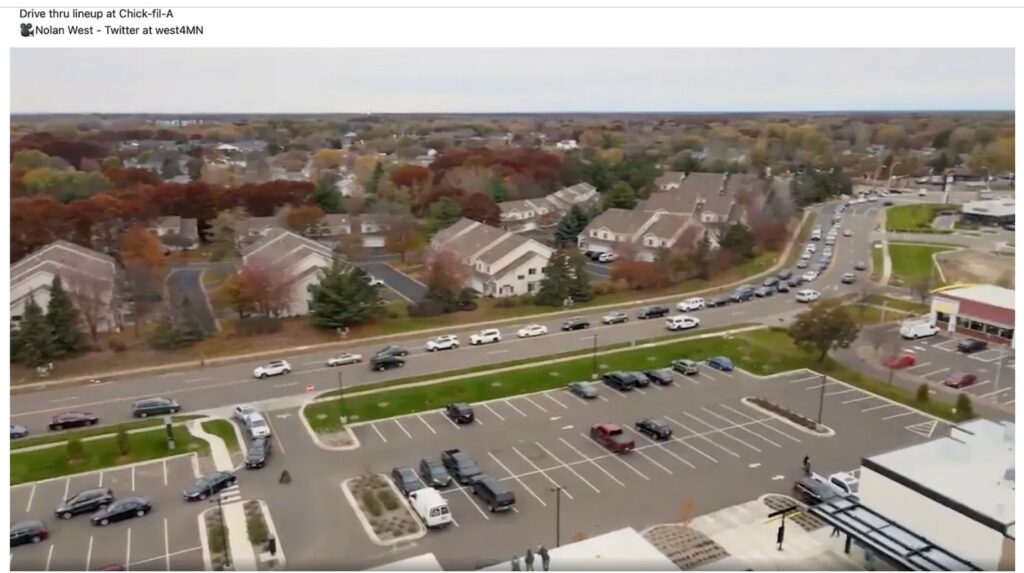

That model means every 11.24 kilograms of CO2 from the burger leaves a trail of paper and plastic waste that is now the purchaser’s responsibility. If bought at a drive-through, there is the idling time; a recent study found that this had increased to an average of six minutes and twenty-two seconds per customer. According to Natural Resources Canada, a 3-litre engine idling releases 69 grams of CO2 per minute, so the average wait time adds almost another half a kilo of CO2 to the meal. And, of course, we are not including the drive to the restaurant in the first place. The necessary drive is because of the design of our suburbs are based on the automobile.

It could be much worse than 6:22; watch Tom Flood’s video of people lining up to get a chicken sandwich. They might be idling for half an hour.

Americans eat approximately fifty billion burgers a year, averaging three per week. Just cutting back on burgers could reduce their impact on climate significantly. Tim Searchinger and associates at the World Resources Institute write:

Reining in climate change won’t require everyone to become vegetarian or vegan, or even to stop eating beef. If ruminant meat consumption in high-consuming countries declined to about 50 calories a day, or 1.5 burgers per person per week—almost half of current U.S. levels and 25% below current European levels, but still well above the national average for most countries—it would nearly eliminate the need for additional agricultural expansion and associated deforestation.

But imagine how much bigger the impact would be if everyone weren’t driving and idling in these massive new airports for burgers. These are likely doing more damage to our health, our climate, our cities, and our culture than the burgers themselves. And unfortunately, as The New York Times article points out, this is the future of food. Severson concludes by quoting a Los Angeles columnist:

“Despite the war against the combustible engine, we are all stuck in cars, and we are all pressed for time, so all roads for Americans eventually lead to the drive-through.”