Why the Fed’s present rate hike campaign is almost unprecedented – by New Deal democrat Just how unprecedented is the Fed’s current rate hike policy? Since the Fed started actively managing the Fed Funds rate in the late 1950s, only two other occasions are similar. The reason the Fed is hiking rates is to combat inflation. But, as I have pointed out in the past, the post-pandemic Boom is very similar to the immediate post-WW2 Boom. In 1947 in the face of 20% YoY inflation, the Fed did – basically nothing. It raised the discount rate from 1% to 1.5%: Prices stabilized on their own once they reached the limit of ordinary consumers to bear. There was a brief inventory-led recession in 1948, and the economy proceeded to motor right forward.

Topics:

NewDealdemocrat considers the following as important: politics, Present Fed Rate, US EConomics, US/Global Economics

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Skidelsky writes Lord Skidelsky to ask His Majesty’s Government what is their policy with regard to the Ukraine war following the new policy of the government of the United States of America.

NewDealdemocrat writes JOLTS revisions from Yesterday’s Report

Joel Eissenberg writes No Invading Allies Act

Ken Melvin writes A Developed Taste

Why the Fed’s present rate hike campaign is almost unprecedented

– by New Deal democrat

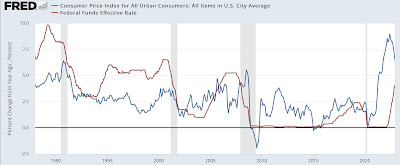

Just how unprecedented is the Fed’s current rate hike policy? Since the Fed started actively managing the Fed Funds rate in the late 1950s, only two other occasions are similar.

The reason the Fed is hiking rates is to combat inflation. But, as I have pointed out in the past, the post-pandemic Boom is very similar to the immediate post-WW2 Boom. In 1947 in the face of 20% YoY inflation, the Fed did – basically nothing. It raised the discount rate from 1% to 1.5%:

Prices stabilized on their own once they reached the limit of ordinary consumers to bear. There was a brief inventory-led recession in 1948, and the economy proceeded to motor right forward.

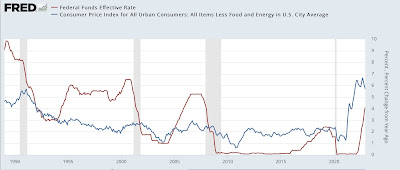

In 2022, the Fed raised rates by 4% in the last 10 months of the year, one of the most aggressive rate hike regimes in history, as shown in the below graph of the YoY change in the Fed funds rate:

Inflation peaked in June. Since then, the Fed has continued to hike rates by 2.75%:

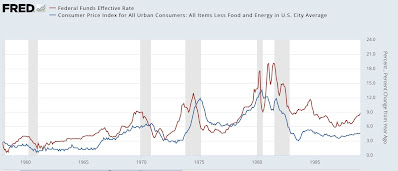

Not only was the 2022 rate hike regime among the most aggressive, but it was unusual in another way. As shown in the below graph, in all other occasions of significance but two, the Fed raised rates coincident with *rising* inflation. The Fed stopped hiking rates before or at most shortly after inflation peaked:

Indeed, typically once inflation started declining, the Fed started to *lower” rates, generally in the face of a weakening economy. By contrast, last year the YoY change in the CPI peaked in June. Since then, the Fed has hiked rates by another 2.75%.

There have only been 4 other times in the past 60+ years that the Fed has continued to raise rates after inflation peaked. Two of those were barely significant, involved rate hikes of only 0.5%. In 1997, the Fed funds rate increased from 5.25% to 5% as inflation declined from 3.4% to 1.4%. In 2018-19, the Fed funds rate was increased from 2% to 2.5% as inflation declined from 2.9% to 1.5%. Neither of those were associated with a recession (the 2020 recession being caused by the pandemic).

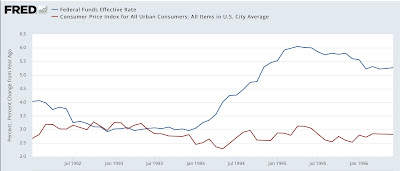

Two other times involved rate hikes 2% to 3% or less that were associated with slowdowns but no recessions. In 1984, the Fed funds rate was hiked over 5 months from 9.5% to 11.75%, as inflation declined from 4.9% to 4.3%:

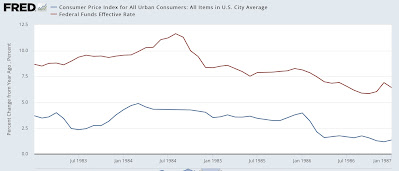

In 1994-95, the Fed funds rate was hiked from 3% to 6% over 17 months, even as inflation varied only from 2.8% to 2.3% to 3.1%:

There was a sharp slowdown – enough perhaps not coincidentally to contribute to the GOP obtaining a majority in the House of Representative for the first time since the Great Depression – but no recession.

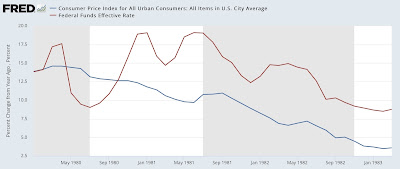

By far the biggest episode occurred in 1980 and 1981. In April 1980 the Fed funds rate peaked at 17.5% exactly as inflation peaked at 14.6%. Thereafter, despite inflation receding to 13.2%, the Fed under Paul Volcker renewed a rate hike campaign, going from 9% to 19%, even as inflation continued to cool to 9.7%. The deep 1981-82 recession, that saw unemployment rise to over 10% for the first time since the Great Depression, ensued:

The current Fed rate hike campaign is more serious than any but the 1980-81 hikes. And even in 1994 inflation was mainly going sideways, not declining. That leaves only the 1984 episode as the only other one truly comparable.

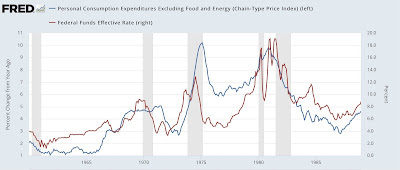

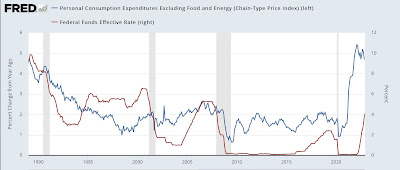

Using core inflation, the situation is the same, with the exception that inflation has not declined significantly at present, solely due to the prominence of the badly lagging measure of owner’s equivalent rent that makes up 40% of the metric:

And it is similar if I use the core personal consumption expenditure deflator as well, with the exception of 1969, where the Fed continued to raise rates into a recession as the core deflator peaked but stabilized there. In our present situation the core deflator has declined -0.5% from 5.2% last February to 4.7% in November:

To summarize: over the past 60+ years, the Fed has normally only raised rates as inflation was rising, and stopped or reversed course once inflation began to decline. Several of the exceptions are not significant, involving rate hikes of 0.5% as inflation declined. One (1994) involved rate hikes in the face of relatively flat inflation, and of the remaining two, one (1984) contributed to a sharp slowdown in the economy with no recession. The other (1980-81) contributed to one of the two worst recessions since the Great Depression, and was justified by Volcker as being necessary to uproot inflationary expectations and a wage-price spiral.

There is very little evidence of any wage-price spiral or embedded future expectations at present. And yet the Fed has continued to hike rates even as inflationary pressures have ebbed (and outside of Owner’s Equivalent Rent, appear contained).