This report dropped into my email box a day or so ago. It hits upon a topic which has plagued big cities since before I was a child. Early-on in Chicago, urban renewal was the thought to be the right idea and the wrong concept. Public housing development in Chicago, Illinois. Cabrini-Green was a model of successful public housing. Poor planning, physical deterioration, and managerial neglect, coupled with gang violence, drugs, and chronic unemployment changed it. It turned into a national symbol of urban blight and failed housing policy. In 2000 the Chicago Housing Authority (CHA) began demolishing Cabrini-Green buildings as part of an ambitious and controversial plan to transform all of the city’s public housing projects. The last of the

Topics:

Angry Bear considers the following as important: Affordable Rental Housing, Journalism, politics, US EConomics

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Skidelsky writes Lord Skidelsky to ask His Majesty’s Government what is their policy with regard to the Ukraine war following the new policy of the government of the United States of America.

NewDealdemocrat writes JOLTS revisions from Yesterday’s Report

Joel Eissenberg writes No Invading Allies Act

Ken Melvin writes A Developed Taste

This report dropped into my email box a day or so ago. It hits upon a topic which has plagued big cities since before I was a child. Early-on in Chicago, urban renewal was the thought to be the right idea and the wrong concept.

Public housing development in Chicago, Illinois. Cabrini-Green was a model of successful public housing. Poor planning, physical deterioration, and managerial neglect, coupled with gang violence, drugs, and chronic unemployment changed it. It turned into a national symbol of urban blight and failed housing policy. In 2000 the Chicago Housing Authority (CHA) began demolishing Cabrini-Green buildings as part of an ambitious and controversial plan to transform all of the city’s public housing projects. The last of the buildings was torn down in 2011.

A turning point for Chicago’s public housing occurred in 1950. By that time, those most in need of affordable housing in Chicago were African Americans, whose numbers were rapidly expanding, primarily because of the northward migration of Southern blacks. The CHA and Chicago’s city council needed to decide where to build new public housing. The CHA proposed a variety of sites, including many vacant areas bordering white neighborhoods. The city council insisted primarily on clearing already existing slums in African American neighborhoods to provide space for new higher-capacity buildings. After a lengthy, racially charged public debate, the city council’s vision won out. The outcome would have a dramatic impact on public housing in Chicago for the rest of the 20th century.

Most of the new public housing that followed, built in the 1950s and ’60s under Mayor Richard J. Daley, came in the form of massive blocks of high-rise apartments. In 1958 and next to the Frances Cabrini Homes, construction was completed on the Cabrini Extension known as the “Reds.” Partly called such because of the buildings’ red brick exteriors. The Reds consisted of 15 buildings of 7, 10, or 19 stories. In 1962 the William Green Homes called the “Whites,” were completed. Located north and west of the Cabrini Extension, they consisted of eight white concrete buildings 15 or 16 stories tall.

All I remember of Cabrini Green was row upon row of tall apartment buildings. It was a tough area to live in and there were issues with crime. People were crowged into a small area with few places to go.

US Affordable Rental Housing Policy Either Doesn’t Make Any Sense or Is Working as Intended

Authored by Algernon Austin with additional information by Angry Bear and a former Chicago Citizen

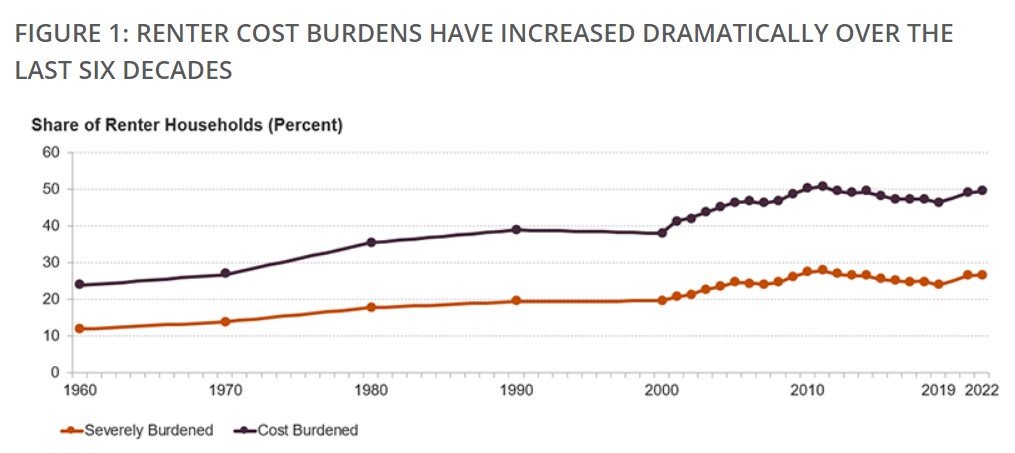

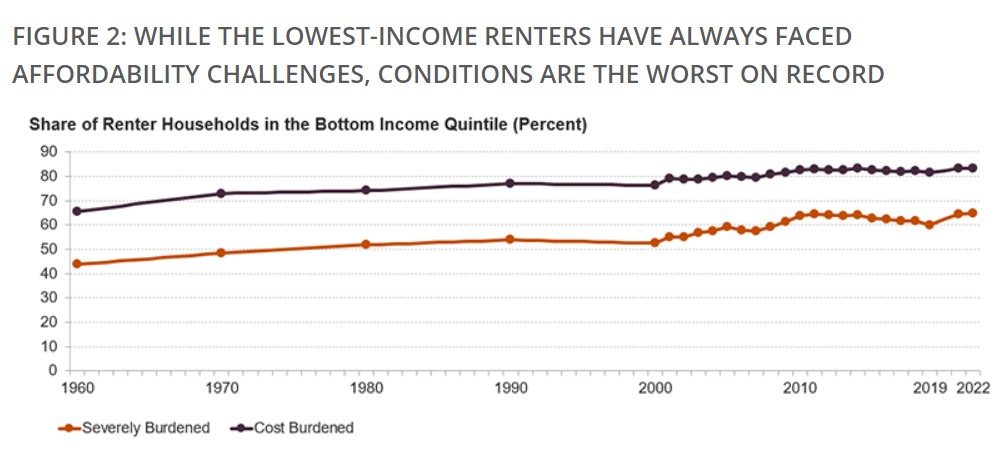

Affordable rental housing policy fails to provide sufficient affordable rental housing decade after decade, yet policymakers continue to do largely the same things. A researcher at the Joint Center for Housing Studies recently observed in 1960, about 45 percent of renters in the bottom income quintile spent more than 50 percent of their income on housing costs. Today, it is about 65 percent. Renters below the official poverty line spend on average 78 percent of their income on housing. Looking at the costs to income comparison, at what point do policymakers admit the policies and plans have failed renters?

Forty- Five percent of renters in the bottom income quintile spent more than fifty percent of their income on housing costs.

Today, the housing rental cost expenditure is about 65 percent.

It Doesn’t Make Sense: The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit

Affordable rental housing policy primarily relies on the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC). The tax credit appears to be a rather bad idea if one is interested in addressing the affordable rental housing crisis. It has a number of problems, but two of them should be considered fatal flaws:

First, LIHTC is not good at providing low-income rental housing. The Joint Center for Housing Studies states,

“LIHTC does not necessarily protect a renter from cost burdens.”

Lower income renters living in LIHTC units often require on hand additional subsidies to make the housing affordable. The primary policy to create affordable rental housing does not do a very good job of creating affordable rental housing in the first place. Yet, policymakers rely on it more and more.

Secondly, a major problem is LIHTC rentals typically convert to market rate after 30 years (in some cases 15 years). This transition rate might be reasonable if there were an adequate supply of affordable rental housing. But, there is not enough supply. The National Low-Income Housing Coalition estimates the United States has a shortage of 7.3 million rental homes for the lowest-income renters. The Joint Center for Housing Studies finds the country lost 2.1 million rental units for the lowest-income renters between 2012 and 2022. Rentals, affordable rentals are too scarce to allow them to be converted to market-rate housing.

The current estimate is an ~ 325,000 LIHTC rental units will transition to market rate by 2029. The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) rental housing bucket has a hole in its bottom. Since more and more of our affordable rental housing is created by LIHTC, the amount of affordable rentals lost to market conversion will increase over time. The United States already does not build enough affordable rental housing to keep up with demand. Policymakers have created a system that will leading to accelerating losses of affordable rental housing over time. Allowing the loss does not make sense.

However, the Affordable Rental Policy Works Well for Corporations and Investors

Current affordable rental housing policy doesn’t make sense if the goal is to provide affordable housing. If the goal is to create market conditions beneficial to real estate developers and investors, the LIHTC appears to be working quite well.

When adequately funded, Public housing is a far more effective method of providing affordable rental housing than LIHTC. The rate of cost-burdened renters is quite low in public housing — much lower than in LIHTC housing. Because of this, there are very long waiting lists and tremendous demand for public housing.

The private real estate industry’s perspective of public housing being, it is a serious threat because of cost.

“From the beginning, the real estate industry bitterly fought public housing of any kind,” Richard Rothstein stated in The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. Rothstein adds the industry later lobbies to structure public housing so it could be underfunded. Today, after the passing of the Faircloth Amendment, Congress has prohibited the increase in the number of public housing units built by the federal government in spite of the fact people are, in some cases, waiting for decades to get into public housing.

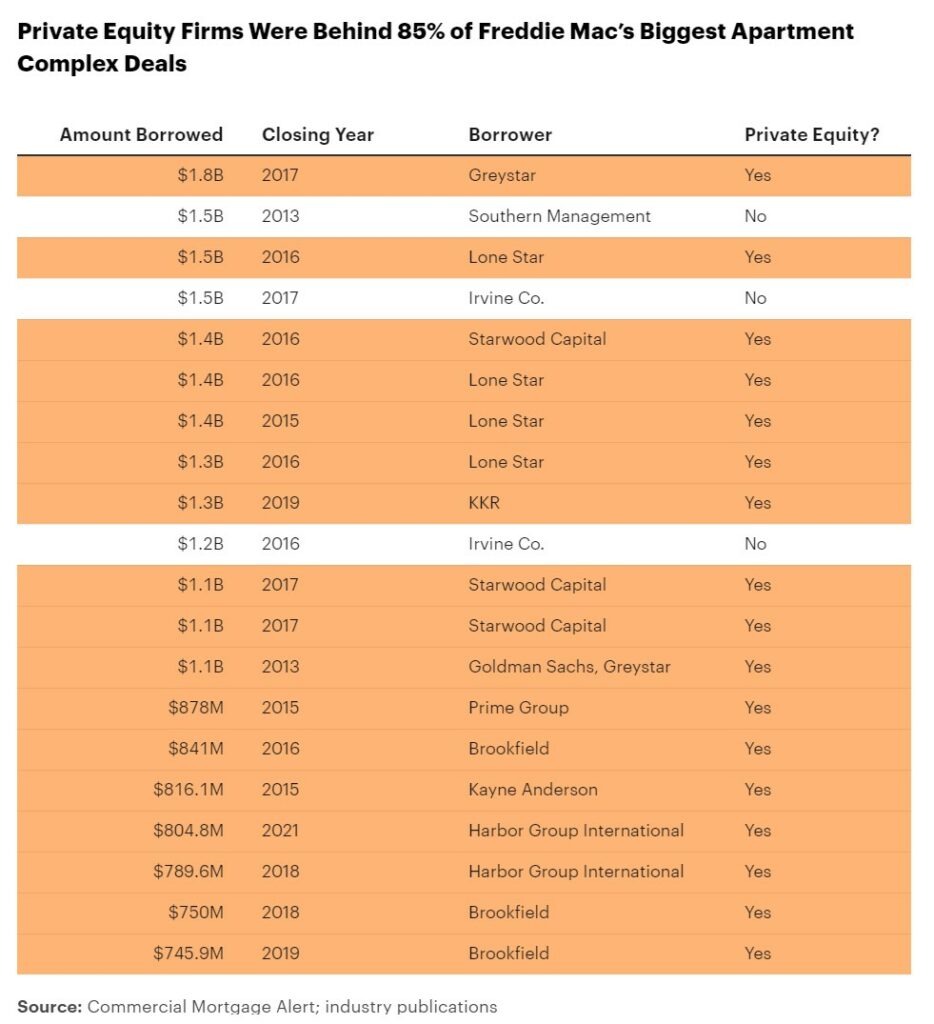

In addition to investors receiving more and more via tax credits from the LIHTC program, the Joint Center for Housing Studies reports corporate owners make up a growing share of the rental housing market. (Corporate share of rental properties ranges from 5 to 24 units nearly doubled between 2001 and 2021.) More private equity firms have also moved into the rental housing market. While more and more renters are have greater costs, it appears more corporations and investors are making good profits. However . . .

It is possible to create affordable rental housing policies that work well for renters. There are good social housing models in Europe and Asia. Social housing is nonprofit housing. In European models, it is not impossible to have just the lowest income households located together. Such a grouping tends to provide it with a stronger political and economic base.

The good news is US city and state governments are beginning to explore these models. And in Congress, Representatives Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Cori Bush, and Becca Balint, Senator Bernard Sanders and other members of Congress have recognized the need to repeal the Faircloth Amendment. Once the Faircloth Amendment dies, the federal government can move toward constructing affordable, quality social housing.

I am sure some of my fellow Chicagoans will have something to add to this. They know the issues.

Rental Housing Unaffordability: How Did We Get Here? | Joint Center for Housing Studies, harvard.edu.

The Crisis of Affordable Rental Housing in the US, CEPR