Americans hate high prices, and Kamala Harris says she plans to combat them by banning price gouging in food and groceries. But, depending on what form it takes, economists could hate her plan. Vice President Harris, who will formally accept her party’s nomination at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago this week, has laid the blame for high food prices at the feet of businesses. Surveys conducted by Harvard University economist Stefanie Stantcheva show many people and Democrats in particular believe that corporate greed is to blame for inflation. The food industry has pushed back hard on that belief, arguing that the rise in prices has to do with the extraordinary economic reordering caused by the pandemic, which snarled supply chains,

Topics:

Angry Bear considers the following as important: law, price gouging, Uncategorized, US EConomics

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

NewDealdemocrat writes JOLTS revisions from Yesterday’s Report

Americans hate high prices, and Kamala Harris says she plans to combat them by banning price gouging in food and groceries. But, depending on what form it takes, economists could hate her plan.

Vice President Harris, who will formally accept her party’s nomination at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago this week, has laid the blame for high food prices at the feet of businesses. Surveys conducted by Harvard University economist Stefanie Stantcheva show many people and Democrats in particular believe that corporate greed is to blame for inflation.

The food industry has pushed back hard on that belief, arguing that the rise in prices has to do with the extraordinary economic reordering caused by the pandemic, which snarled supply chains, pumped government money into the economy and spiked demand.

GOP candidate Donald Trump, who has frequently complained about high food costs, especially the price of bacon, last week described her plan as “Communist price control.”

Harris’s team has offered few details so far. But here is what economists say about price gouging, what it is, and whether it is ideal—or even possible—to try to curb it.

Why groceries?

While food inflation has eased some recently, prices remain much higher than they were before the pandemic. As of July, consumer prices for food at home were 26% higher than they were at the end of 2019, whereas the prices for goods excluding food and energy items were up just 14%. Food prices hit hard psychologically too—people take frequent trips to the grocery store and can skimp only so much on what they eat.

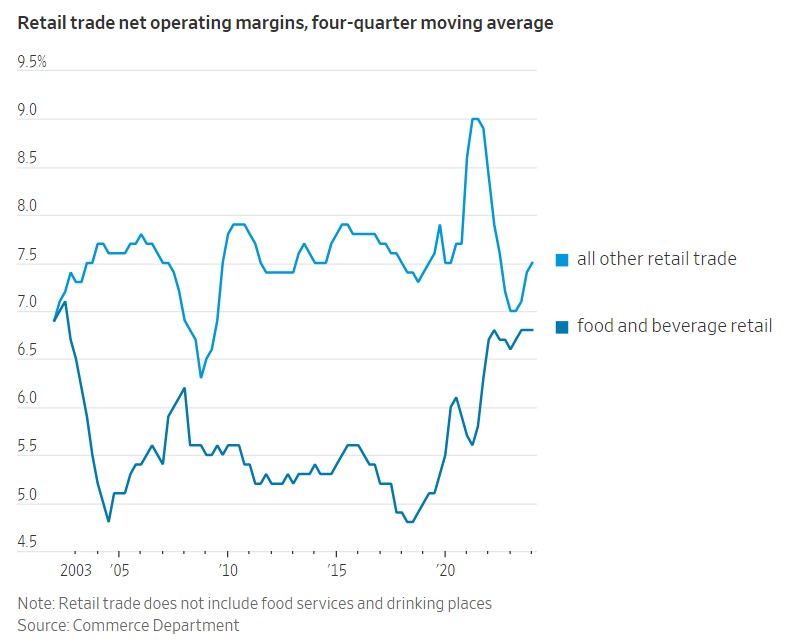

Ernie Tedeschi, formerly on the staff at President Biden’s Council of Economic Advisers, now director of economics at the Budget Lab at Yale University, points out that margins at food and beverage retailers have remained elevated relative to before the pandemic, while margins at other retailers, such as clothing and general merchandise stores, haven’t.

That could, he cautions, be a reflection of consumer choice—customers might have changed their preferences to items that are more profitable, such as private-label brands. Regardless, “economists need to be curious about this and figure out what is going on,” Tedeschi said. Retail trade net operating margins, four-quarter moving average Source: Commerce Department Note: Retail trade does not include food services and drinking places.

What is price gouging?

Outside of extreme examples—such as Martin Shkreli raising the price of a decades-old drug used to treat AIDS patients from $13.50 a pill to $750 in 2015—identifying price gouging, and crafting policies against it, can be difficult.

Rules against price-gouging can in effect become price controls. Standard economic theory shows that imposing a price ceiling on a product can discourage sellers, reducing the amount of a product that gets sold, leading to shortages. Rent-control policies are an example of a price ceiling that has become a staple of introductory economics textbooks, and as a group, most economists think rent control is a bad idea.

“It can be very hard to create any price control that is not gameable,” said Michael Sinkinson, an economist at Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management who was also on Biden’s Council of Economic Advisers. “How do you set a price control? What is the right benchmark?”

Does controlling prices ever work?

Economists’ views on rules that prevent price gouging during extreme events, such as severe storms, are more mixed. Such laws are common: During a state of emergency in Florida, for example, it “is unlawful to rent, sell, lease, offer to rent, sell, or lease essential commodities, dwelling units, or self-storage facilities at an unconscionable price.” Shortly after the Covid-19 crisis struck, then-President Trump issued an executive order to prevent price gouging for medical supplies.

Some economists contend that raising prices in these circumstances can be predatory, because supply is limited to whatever businesses have on hand. But others argue that the signal prices send are important: A jump in the price of water at an island that gets hit by a hurricane creates an incentive for water to get shipped in quickly, while an artificially low price during a time of shortage might encourage hoarding,

One place economists do accept some degree of price controls is in natural monopolies, points out Harvard economist Greg Mankiw, the author of a widely used introduction to economics textbook and a chair of the Council of Economic Advisers during former President George W. Bush’s administration. Utilities are an example.

But the food business isn’t a monopoly, Most people, but not all, have the option of going to another store if one store raises its prices too much. Among economists, said Mankiw,

“Our assumption is that firms are always greedy and it is the forces of competition that keeps prices close to cost.”

Harris, for her part, has also said she wants to increase competition. Last week saying . . .

“My plan will include new penalties for opportunistic companies that exploit crises and break the rules, and we will support smaller food businesses that are trying to play by the rules and get ahead.”

The more her plan leans into increasing competition as a way to lower prices, and the less she leans into setting ceilings on prices, the more economists might like what she has to say.

Kamala Harris Wants to Ban Price Gouging. What Do Economists Say? Wall Street Journal.

~~~~~~~

Along those lines and one article I read tonight was by ProPublica covering a system called RealPage.

“How a Secret Rent Algorithm Pushes Rents Higher,” ProPublica.

The software’s design and growing reach have raised questions among real estate and legal experts about whether RealPage has birthed a new kind of cartel that allows the nation’s largest landlords to indirectly coordinate pricing, potentially in violation of federal law.

Experts say RealPage and its clients invite scrutiny from antitrust enforcers for several reasons, including their use of private data on what competitors charge in rent. In particular, RealPage’s creation of work groups that meet privately and include landlords who are otherwise rivals could be a red flag of potential collusion, a former federal prosecutor said.

At a minimum, critics said, the software’s algorithm may be artificially inflating rents and stifling competition.

“Machines quickly learn the only way to win is to push prices above competitive levels,” said University of Tennessee law professor Maurice Stucke, a former prosecutor in the Justice Department’s antitrust division.

What is apparent here is maybe technology is stifling competition and what one might call fair markets. The U.S. Department of Justice announced Friday that it is suing the real estate company RealPage, saying it engaged in a price-fixing scheme to drive up rents.