A conversation on providing for disability. The right to work as an equal also extends to the disabled. Contingencies are made for the disabled and is a key factor in having the ability to provide for themselves. Doors that open with the touch of a button. Wheelchair accommodations to go up a step or a set of stairs. Access to the use of bathrooms. Adequate desks and chairs. In which case if not available, society takes away the ability of the disabled to secure economic equality with those without disabilities. And such falls back on society to provide food and shelter as well as other means to live as people. Disability justice is key to the pursuit of economic equality; the latter requires commitment to the former. There has to be a

Topics:

Angry Bear considers the following as important: disability, law, US EConomics

This could be interesting, too:

NewDealdemocrat writes JOLTS revisions from Yesterday’s Report

Joel Eissenberg writes No Invading Allies Act

Bill Haskell writes The North American Automobile Industry Waits for Trump and the Gov. to Act

Bill Haskell writes Families Struggle Paying for Child Care While Working

A conversation on providing for disability.

The right to work as an equal also extends to the disabled. Contingencies are made for the disabled and is a key factor in having the ability to provide for themselves. Doors that open with the touch of a button. Wheelchair accommodations to go up a step or a set of stairs. Access to the use of bathrooms. Adequate desks and chairs.

In which case if not available, society takes away the ability of the disabled to secure economic equality with those without disabilities. And such falls back on society to provide food and shelter as well as other means to live as people.

Disability justice is key to the pursuit of economic equality; the latter requires commitment to the former. There has to be a way to provide for oneself. Economic inequalities disabled people face are rooted in the same systems of oppression that marginalize them socially and politically. Disability justice demands a comprehensive understanding of how these systems intersect to deny disabled individuals economic security, independence, and dignity.

The next few charts and graphs tackle the enormity of the issue. Another good economic piece by CEPR.

Employment and Labor Force Participation

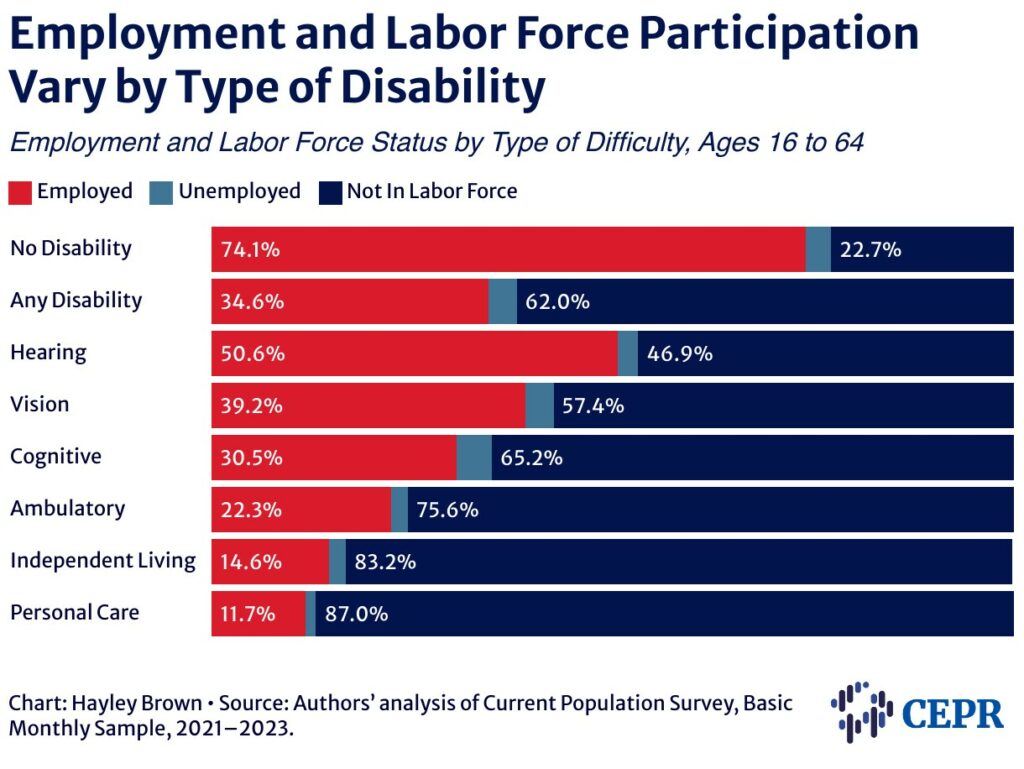

Employment plays a critical role in economic security. Individuals with disabilities face significant barriers to participation. Employment rates for working-age disabled individuals are considerably lower than for their non-disabled counterparts. However, disability is not a monolith, and levels of both employment and labor force participation vary substantially by type of difficulty. Figure 2.1a shows the share of those ages 16 to 64 who were employed, unemployed, and not in the labor force by disability status and type of difficulty. Just over a third (34.6 percent) of those with a disability were employed, compared to nearly three-quarters (74.1 percent) of those without a disability. Among those with disabilities, the employed share also varied appreciably by type of difficulty. Over half of those who experienced hearing difficulty were employed, compared to only 11.8 percent of those who reported difficulty with personal care, such as dressing or bathing.

Figure 2.1A

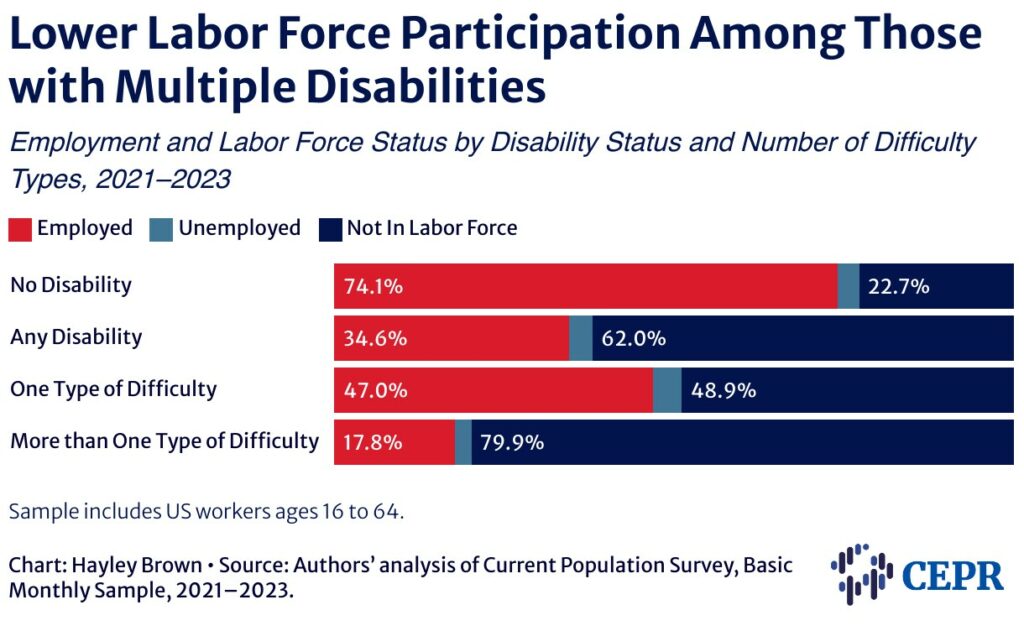

The number of types of disability also plays a role. Figure 2.1b shows the share of those ages 16 to 64 who were employed, unemployed, and not in the labor force by disability status, and whether those with disabilities experienced only one type of difficulty or multiple types of difficulty. Less than 20 percent (17.8 percent) of those with multiple types of difficulty were employed, compared to 47 percent of those with only one type of disability.

Figure 2.1B

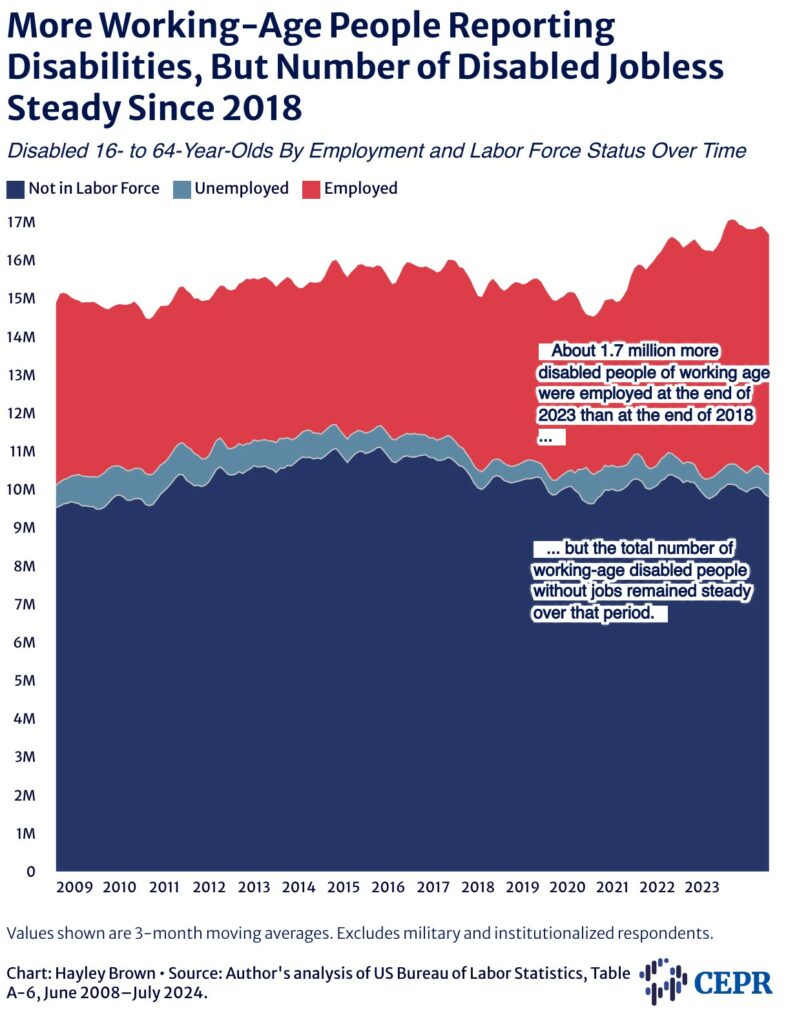

Lower levels of employment among working-age people with disabilities is not a new phenomenon. Figure 2.2 shows employment levels and labor force participation among working-age people with disabilities over time. While the number of employed disabled people aged 16 to 64 increased substantially in 2023, the number without jobs (which includes both the unemployed and those not in the labor force) has been largely steady since 2018. As has been previously noted, this may mean that recent increases in employment among disabled people of working age reflect an overall increase in the number of disabled working-age people, rather than an increase in employment or labor force participation among disabled people who were previously not employed. This increase in disability among working-age people may reflect the impact of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and, in particular, of Long COVID.

Figure 2.2

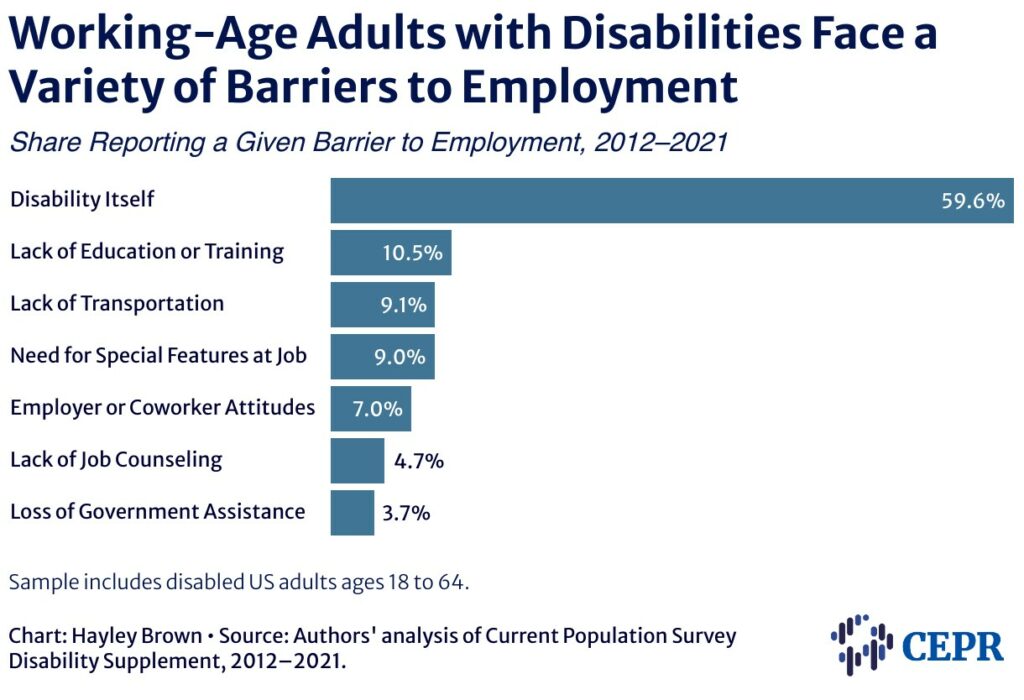

People with disabilities face numerous barriers to employment. Figure 2.3 shows the share of disabled US adults ages 18 to 64 who said they faced a given employment barrier (the options are not mutually exclusive, meaning respondents could say they faced more than one type of barrier). The most commonly cited barrier was the disability itself, followed by a lack of education or training. While this may seem like a clear rebuke of the social model of disability, it may also reflect the ubiquity of systemic obstacles within a capitalist structure. That said, it is also true that not everyone with a disability will be able to participate in the labor force. The just course requires supporting disabled individuals in paid employment to the fullest extent, without depriving those whose disabilities are not compatible with paid work of economic security and dignity.

Figure 2.3

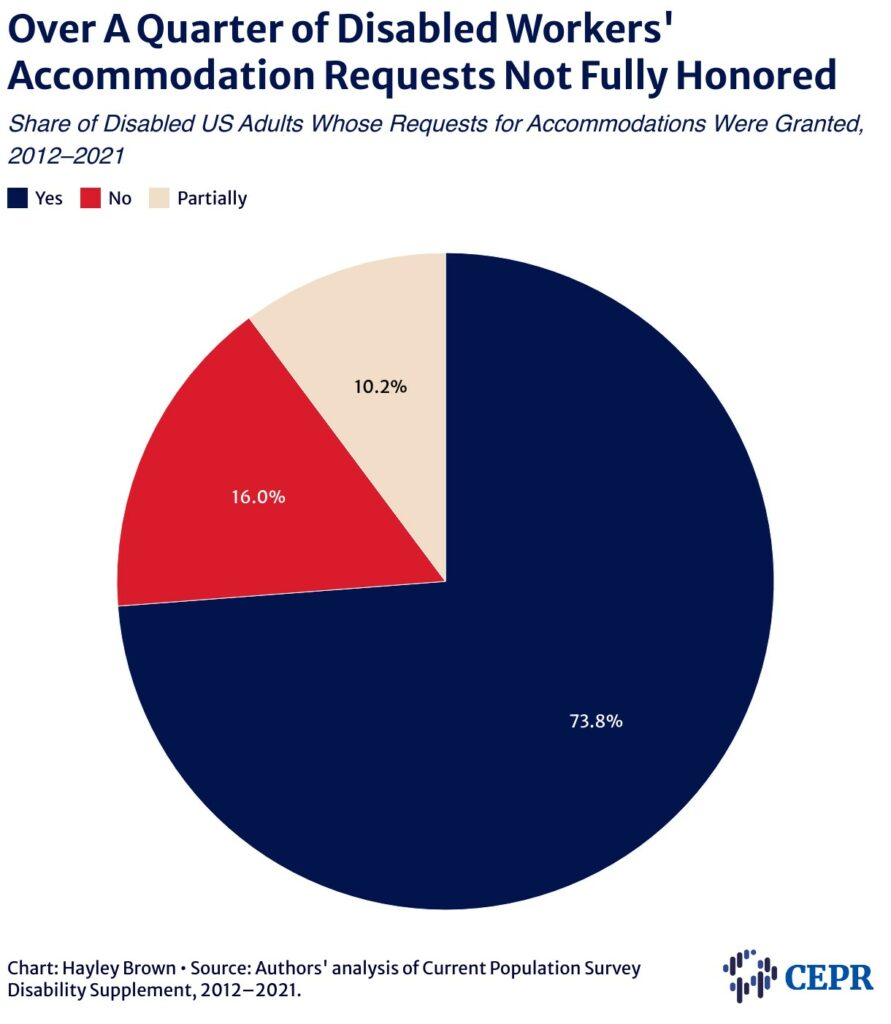

While the ADA requires that employers subject to the law make reasonable accommodations for workers with disabilities, employers and employees may not see eye-to-eye on what is reasonable, and employers frequently fail to meet disabled employees’ accommodation needs. Figure 2.4 shows that over a quarter of disabled workers’ requests for accommodations were not fully honored. Employers partially fulfilled just over 10 percent of requests, and 16 percent of requests were denied altogether. The share of disabled workers who said they requested an accommodation at all was relatively small, suggesting that either their workplaces are already sufficiently accessible to meet their needs or that they are reluctant to request an accommodation, even if they would benefit from having one. While ideally more workplaces would shift to a universal design framework rather than relying primarily on accommodations, these results suggest that the accommodations framework as currently implemented is failing to meet the accommodation needs of a considerable portion of disabled workers.

Figure 2.4

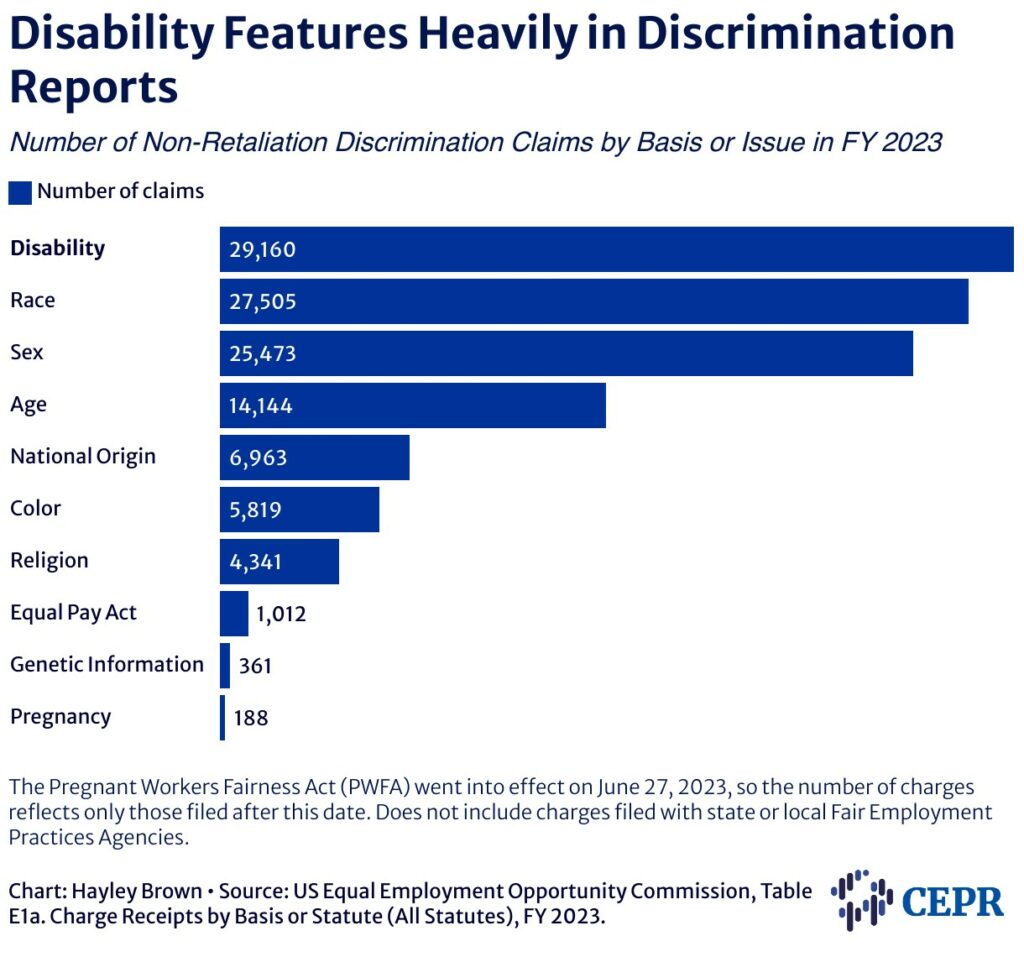

People with disabilities must contend with discrimination both in and out of the workplace. This includes but is not limited to employers’ refusal to reasonably accommodate disabilities in the workplace. Figure 2.5 shows the number of discrimination claims made to the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission by basis or issue. Disability was the most commonly cited non-retaliatory basis for discrimination, with over 29,000 reports in fiscal year 2023. This likely represents an undercount, as it excludes charges filed with state or local Fair Employment Practices Agencies. Moreover, many incidents of discrimination never result in a formal filing, because most disabled Americans simply do not have the time, money, and physical energy required to see through a years-long legal process to sue employers. These violations also, by nature, only include individual instances of discrimination covered by civil rights laws like the ADA. As Marta Russell notes, such laws do not address or remedy more systemic forms of discrimination against people with disabilities, as these structural barriers often derive from entrenched capitalist power relationships.

Figure 2.5

The Disability and Economic Justice Chartbook, Center for Economic and Policy Research, Hayley Brown, Julie Yixia Cai, Tori Coan.