There is a far greater detailed article at the New England Journal of Medicine. Angry Bear did not have the space to rightfully do the article justice. Instead, we concentrated on the letter to the editor written April 19, 2024. The article was published on May 30, 2024. Just the brief letter to the editor is explosive. We did add chart S5 which gives a breakdown by region. I believe this better explains the concern by the authors of the Firearm death toll amongst black youth. Perhaps, SCOTUS has a cure for this? Too many bullet-spewing weapons floating around in society. And too much time spent without school or work to go too. Increasing Firearm-Related Deaths among U.S. Black Rural Youths by Allison Lind, M.P.H., A.P.R.N.-C.N.P., Susan

Topics:

Angry Bear considers the following as important: Black Rural Youths, Education, firearms, law, politics

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Skidelsky writes Lord Skidelsky to ask His Majesty’s Government what is their policy with regard to the Ukraine war following the new policy of the government of the United States of America.

Joel Eissenberg writes No Invading Allies Act

Ken Melvin writes A Developed Taste

Bill Haskell writes The North American Automobile Industry Waits for Trump and the Gov. to Act

There is a far greater detailed article at the New England Journal of Medicine. Angry Bear did not have the space to rightfully do the article justice. Instead, we concentrated on the letter to the editor written April 19, 2024. The article was published on May 30, 2024.

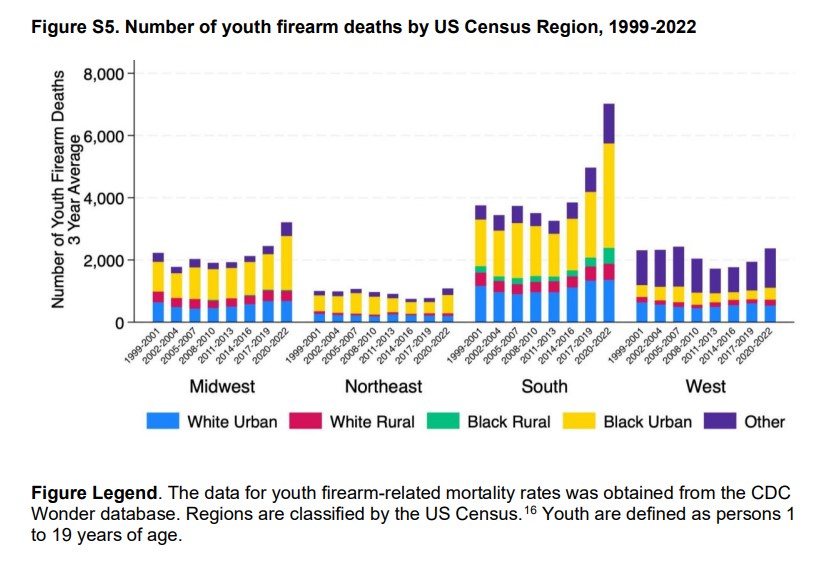

Just the brief letter to the editor is explosive. We did add chart S5 which gives a breakdown by region. I believe this better explains the concern by the authors of the Firearm death toll amongst black youth. Perhaps, SCOTUS has a cure for this?

Too many bullet-spewing weapons floating around in society. And too much time spent without school or work to go too.

Increasing Firearm-Related Deaths among U.S. Black Rural Youths

by Allison Lind, M.P.H., A.P.R.N.-C.N.P., Susan M. Mason, Ph.D., Elizabeth Wrigley-Field, Ph.D.

New England Journal of Medicine

To The Editor:

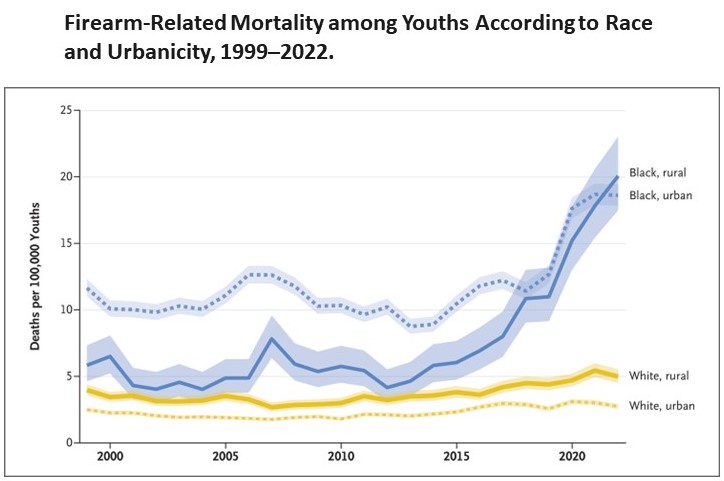

After decades of decline, the United States saw a nearly 20% increase in all-cause mortality among children and adolescents 1 to 19 years of age (hereafter, youths) from 2019 through 2021.1 This increase can be attributed to an accelerating upward trend in firearm-related deaths, disproportionately concentrated among Black youths. It’s beginning in 2013 has been exacerbated during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic years (Supplementary Appendix), available with the full text of this letter at NEJM.org).2,3 Whether this increase is concentrated in urban areas, a pattern consistent with historical trends, is unknown.4,5

We analyzed 1999–2022 data regarding underlying causes of death, which were obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Wonder database, and classified firearm-related deaths using codes from the International Classification of Disease. We calculated crude mortality per 100,000 youths and estimated the proportion of deaths related to firearms, as stratified according to race or ethnic group and urbanicity categories (urban vs. rural; see Tables S1 and S2 and Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Firearm-related mortality among youths has increased since 1999, most notably among Black rural youths, who make up 9% of the Black youth population (Figure 1). In 2013, the percentages of firearm-related deaths among Black and White rural youths were similar, with firearms accounting for 12% of deaths (53 of 437) among Black youths and 11% of deaths (282 of 2618) among White youths. By 2022, a third of all deaths among Black rural youths (204 of 594) were firearm related (Fig. S2). That year, the firearm-related mortality among Black rural youths was 20.0 per 100,000 (95% confidence interval [CI], 17.5 to 23.0), four times as high as that among White rural youths (5.0; 95% CI, 4.5 to 5.5). Despite Black youths making up only 10% of the rural population between 1 and 19 years of age, they accounted for 30% (204 of 690) of all firearm-related fatalities among rural youths.

In sharp contrast with patterns observed before 2018, firearm-related deaths among Black rural youths in 2022 equaled or surpassed the rate among Black urban youths (18.6 per 100,000; 95% CI, 17.8 to 19.4). Of the 2279 firearm-related deaths among Black youths in 2022, nearly 9% occurred among youths residing in rural settings. These deaths were overwhelmingly (86%) homicides (Fig. S3), were concentrated in the South (Fig. S4 and S5), and were more common among older adolescents (Fig. S6).

The study reveals a critical, overlooked aspect of rising youth mortality: a quadrupling of firearm-related deaths among Black rural youths, primarily due to homicides. Solutions will require research to understand the unique circumstances driving this epidemic of firearm-related deaths among Black rural youths.

Freedom to carry bullet-spewing-weapons does not promote security, safety or life. In fact, it leads to greater danger.

Allison Lind, M.P.H., A.P.R.N.-C.N.P., Susan M. Mason, Ph.D., Elizabeth Wrigley-Field, Ph.D., University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN

1. Woolf SH, Wolf ER, Rivara FP. The new crisis of increasing all-cause mortality in US children and adolescents. JAMA 2023;329:975-976.

2. Andrews AL, Killings X, Oddo ER, Gastineau KAB, Hink AB. Pediatric firearm injury mortality epidemiology. Pediatrics 2022;149(3):e2021052739-e2021052739.

3. Goldstick JE, Cunningham RM, Carter PM. Current causes of death in children and adolescents in the United States. N Engl J Med 2022;386:1955-1956.

4. Bottiani JH, Camacho DA, Lindstrom Johnson S, Bradshaw CP. Annual research review: youth firearm violence disparities in the United States and implications for prevention. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2021;62:563-579.

5. Probst J, Zahnd W, Breneman C. Declines in pediatric mortality fall short for rural US children. Health Aff (Millwood) 2019;38:2069-2076.