Been writing on Rural and Inner-city hospitals and the lack of funding for them, the buying up of the same by larger entities, and the abuse of the 340B program by the larger hospital. Once the larger hospital buys the inner-city hospital, there is a tendency to cut services and also abuse the 340B program. Rural hospitals are less funded than their city cousins. Programs such as Medicaid and Medicare pay less than their smaller margins than what may be acceptable due to larger margins at their city cousins. This also plays out in staffing as there may not be enough work to maintain the staffing for specialized services. Not much changed for the Covid funding as greater amounts of funding per bed went to the lager hospitals. Initially, smaller

Topics:

Bill Haskell considers the following as important: Conid, Healthcare, hospital bedding, politics

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Skidelsky writes Lord Skidelsky to ask His Majesty’s Government what is their policy with regard to the Ukraine war following the new policy of the government of the United States of America.

Joel Eissenberg writes No Invading Allies Act

Ken Melvin writes A Developed Taste

Bill Haskell writes The North American Automobile Industry Waits for Trump and the Gov. to Act

Been writing on Rural and Inner-city hospitals and the lack of funding for them, the buying up of the same by larger entities, and the abuse of the 340B program by the larger hospital. Once the larger hospital buys the inner-city hospital, there is a tendency to cut services and also abuse the 340B program. Rural hospitals are less funded than their city cousins. Programs such as Medicaid and Medicare pay less than their smaller margins than what may be acceptable due to larger margins at their city cousins. This also plays out in staffing as there may not be enough work to maintain the staffing for specialized services.

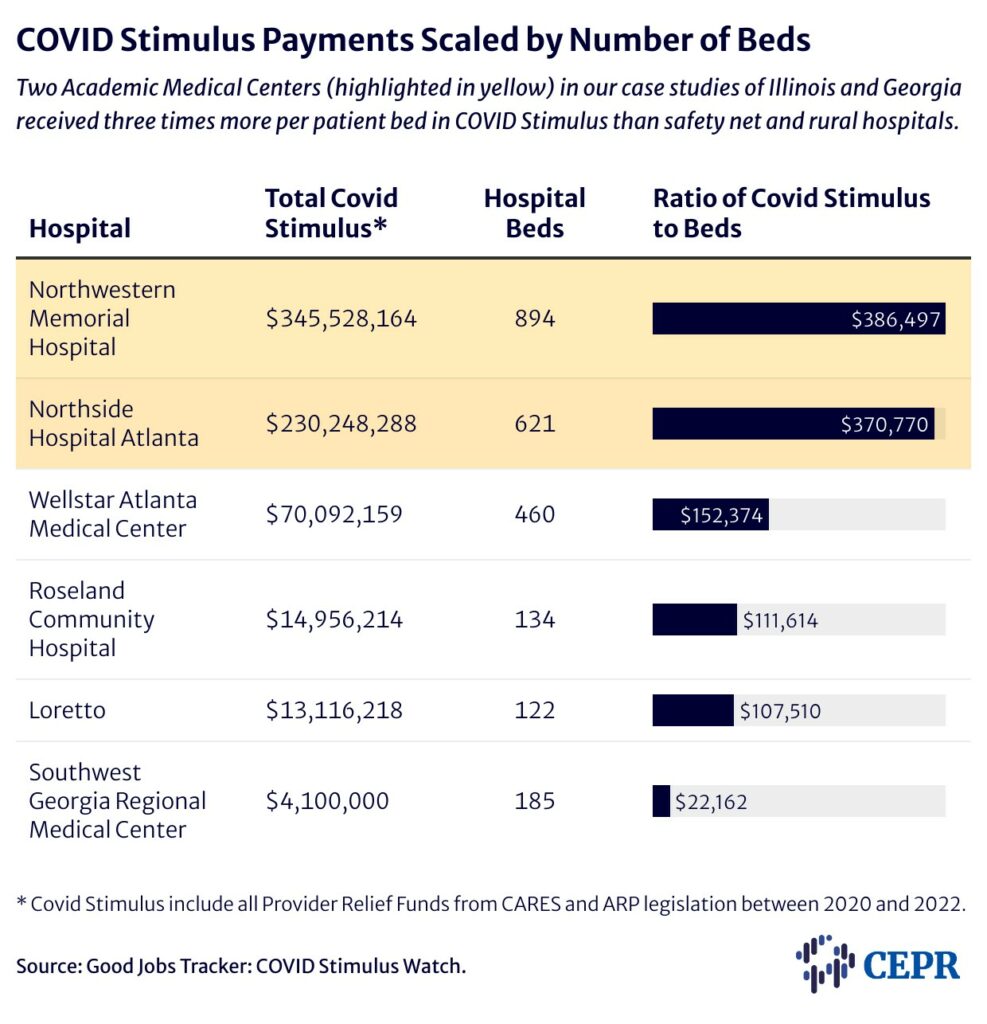

Not much changed for the Covid funding as greater amounts of funding per bed went to the lager hospitals. Initially, smaller hospitals were underfunded as the funding was directed elsewhere. It was not till the end, did smaller entities received funding.

CARES Act Funding: Deadly Inequities in Hospital Bailouts, CEPR

During the first and largest phase of COVID-19 stimulus funding, $50 billion dollars of relief was allocated to hospitals and other provider organizations through a general distribution of funds by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). HRSA allocated $30 billion based on the organizations or clinician’s share of total Medicare fee-for-service reimbursements in 2019 (Ellison 2020). The remaining $20 billion was allocated to hospitals based on the hospital’s net patient revenue in 2019 (Liss 2020).

The general distribution was not based on a hospital’s need for resources to address the pandemic and hospitals and other recipients were not required to use these funds for treating patients. Based on these formulas where patients were more likely to be covered by Medicare or private insurance, the wealthier hospitals received more funding. More funding than safety net hospitals and community health centers, where patients are more likely on Medicaid or uninsured (Abramson 2020).

Private insurers often pay nearly double what Medicare pays for all hospital services (Lopez, Neuman, Jacobson, and Levitt 2020). Notably, the formula did not take into account whether the hospital treated large numbers of COVID-19 patients and did not require hospitals to use CARES Act funds for their care. The first phase of funding came with no strings attached.

High reimbursement can come from having more privately insured patients coming through the door or being able to charge higher rates to private insurance companies because of their market power. If a hospital dominated the market at the point of the HHS funding, they were likely to do well with the formula. A Kaiser Family Foundation study found hospitals with the lowest share of revenue from private insurance received half as much per hospital bed as their counterparts. Those counterparts with the highest share during the first $50 billion general distribution wave of CARES Act funding in April 2020 (Schwartz and Damico 2020).

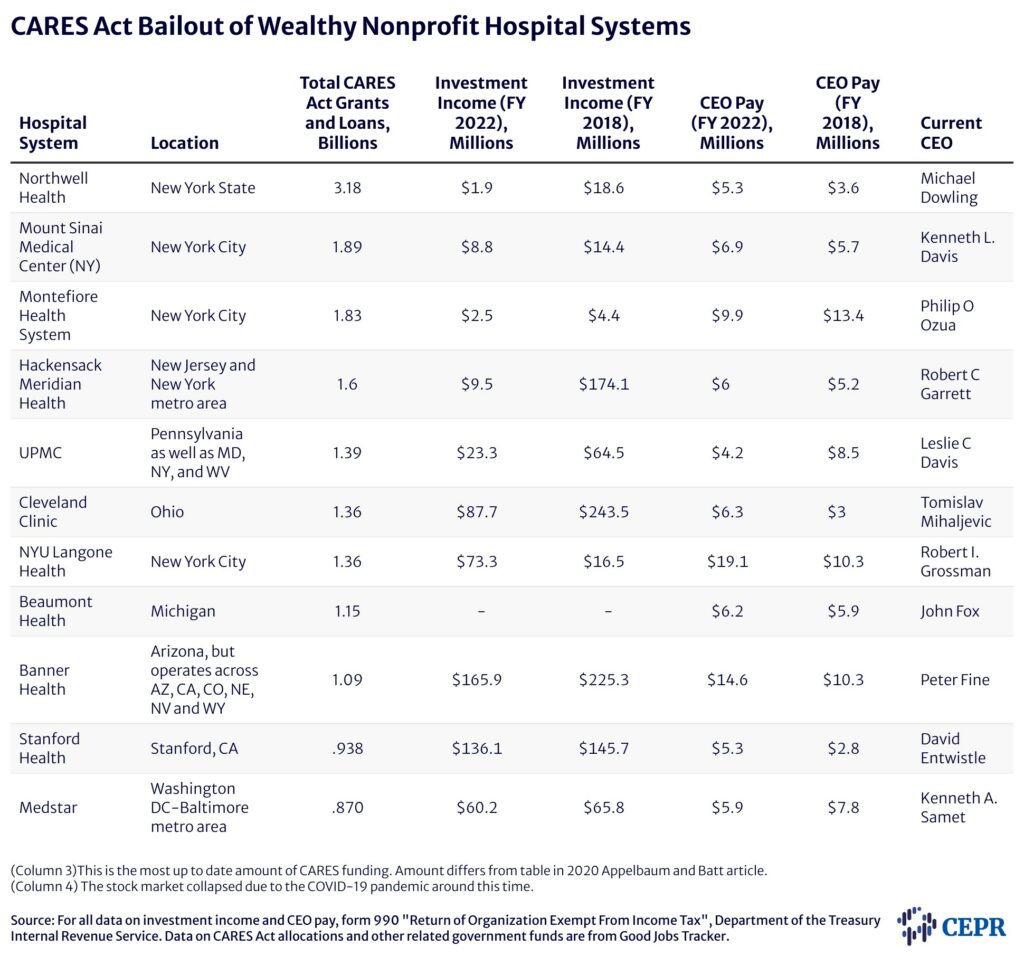

Also the wealthier hospitals with higher levels of Medicare reimbursements, higher private pay patients, or higher prior net revenues received emergency funding from the Provider Relief Fund (PRF) and far more than did hospitals with greater need. More funding than those hospitals those relying on Medicaid or serving rural or lower-income communities.

Based on share of private insurance revenue, the top 10 percent of hospitals received $44,321 per hospital bed. They were more likely to be for-profit institutions, had larger operating margins. These hospitals were also less likely to be teaching hospitals and providing less uncompensated care (a.k.a. charity care) (Schwartz and Damico 2020). The two largest hospital chains, HCA Healthcare Inc. and Tenet Healthcare Corp., both of which own hundreds of hospitals, received $5.3 billion and $2 billion in loans and grants, respectively, in the first wave (Terhune 2020). Within months, HCA returned to strong financial health with stocks soaring and 38 percent higher profits than the previous year (Abelson 2020). The chain ultimately returned a large portion of its relief (Pifer 2020). Along with Kaiser Permanente, it was one of the few wealthy hospital systems to do so.

Hospitals and community health centers serving poorer populations and receiving most of their revenue from Medicaid, as opposed to Medicare and private insurers, went without or received very little of the initial $50 billion CARES Act funding pot. On average, they received just $20,710 per hospital bed.

Only $2.6 billion of the $50 billion paid out went to Medicaid and CHIP providers. Many of these institutions were either in rural areas or poor urban communities where COVID-19 infection rates were higher than in the geographies served by wealthy hospitals (Schwartz and Damico 2020). The disparity in revenue sources of these two groups of hospitals over many decades has led to financial instability of the hospitals serving most of America’s poorest communities. These are the hospitals inundated with COVID-19 patients in the early days of the pandemic. Furthermore, these are the hospitals that, in the immediate aftermath of the pandemic, received the least CARES Act funding to meet the challenge.

Academic Medical Centers typically have access to a safety net of financial resources safety net hospitals do not. Wealthy donors, endowments, and investment income enabled these and other well-endowed hospital systems to build substantial reserves. Despite this disparity in financial resources, CARES Act funding still favored hospitals that could more easily sustain the economic blow of the pandemic (see Table 1). Research shows the hospitals with significant cash on hand received more CARES Act PRF funding per bed than did hospitals with negligible cash available. While hospitals with at least 76 days of cash on hand received $88,000 per bed, hospitals with less than a week of cash on hand received $22,000 per bed on average (Grogan et al. 2021).

Pushback from public health experts and others led to reforms in how later rounds of PRF funds were distributed. The targeted allocations that passed in May 2020 made funds available to hospitals that were most impacted by COVID-19, including smaller and financially strapped community hospitals as well as large academic medical centers with high COVID-19 caseloads. These are the relief targets and amounts:

– $20.7 billion “high-impact” fund intended for hospitals hardest hit by COVID-19,

– $10.9 billion to rural providers,

– $13.1 billion to safety net hospitals,

– $4.8 billion to skilled nursing facilities,

– $4.7 billion to nursing home infection control, quality, and performance,

– and finally $1.6 billion for children’s hospitals and tribal health providers (Coughlin 2022).

For the targeted funding based on COVID-19 prevalence; academic-affiliated hospitals with higher assets prior to COVID-19 and hospitals having higher numbers of COVID-19 cases received higher levels of funding. Yet again, the smaller critical access hospitals received lower levels of financial assistance per bed than their wealthier counterparts (Cantor et al. 2021).

Many hospitals which were mainly rural hospitals and those serving poor communities, were missed in the first three general distribution phases of CARES Act distributions and high-impact distributions. This inequity was addressed to a greater extent in the fourth and final distribution of PRF funds which allocated an additional $8.2 billion to these hospitals in the new Biden administration’s American Rescue Plan (ARP).

This was less than a year after the start of the pandemic and was an improvement from early rounds of stimulus. However, the disparity in nearly all the rounds of CARES Act funding came on the heels of years of unequal funding of U.S. hospitals.

Table 2 displays the COVID Stimulus provided to hospitals in our case studies below in relation to the number of hospital beds at each.

Illustrated in the CEPR report are the effects of inequities in funding on health outcomes of COVID-19 patients by examining the allocation of CARES Act funds to two states: Georgia and Illinois, and the life and death effects for patients. Both of these studies can be found here:

6.2.1 Georgia: A total of $3.2 billion in CARES Act relief was allocated to Georgia as of early December 2020. Around 40 percent went to just 20 providers, leaving the more than 10,000 providers and facilities in the state to share the remainder (Shakoor, Gee, Rapfogel 2020). and here . . .

6.2.2 Illinois: Chicago’s two-tier health system illustrates the stark contrast between the allocation of CARES Act funds to safety net hospitals and to hospitals in university systems. Check out Chicago’s Northwestern Memorial funding per bed versus Chicago’s Loretto and Roseland Community hospital funding per bed.

The availability of health care resources a facility had to treat COVID-19 patients played a major role in patients’ health outcomes and whether they survived the virus. Counties with lower staffing levels were associated with higher COVID-19-related deaths (Epané 2023) as were hospitals whose physical plant included fewer intensive care unit beds (Janke et al. 2021). It mattered where you lived and which hospital you had access to. Counties with higher per-capita incomes tended to have better resourced health care facilities and thus lower COVID-19-related deaths (Epané 2023). Black, Latino, and Native American people died at much higher rates than white people (Hill and Artiga 2022). Residents of rural communities also suffered higher rates of COVID-19-related deaths than did urban residents. Initially, urban counties had higher rates of COVID-19-related deaths, especially at the pandemic’s start. However, recent analysis shows that over the long term, patients from rural counties experienced higher mortality rates and tended to be readmitted more frequently following COVID-19 hospitalization (Yousufuddin 2024).