I bet you've never heard of Slovenia. It's the northernmost Balkan state, squeezed between Austria, Italy and Croatia on the Adriatic coast. It's small, peaceful (by Balkan standards) and prosperous compared to the rest of the Balkans, though that isn't saying much. It is also stunningly beautiful, in a mountains-and-lakes sort of way. It is in many ways rather like Austria.But at the moment, Slovenia is famous not for its lovely scenery, or its important history, or its rich culture. No, it is famous for its banks. And not in a good way. Slovenia's banking crisis is a long-running sore.Slovenia's story is an all too familiar one. After it joined the EU in 2004, it entered the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM II) as a precursor to joining the Euro. EU membership requires free movement of capital across borders, and under ERM II its exchange rate was soft-pegged to the Euro. So it effectively lost control of monetary policy. The result, of course, was a mammoth inflow of foreign funds, a huge credit bubble, an enormous spike in real estate prices, and massive current account and fiscal deficits.

Topics:

Frances Coppola considers the following as important: Balkans, banks, Debt, Financial Crisis, GDP, Slovenia, sovereign debt

This could be interesting, too:

Angry Bear writes GDP Grows 2.3 Percent

NewDealdemocrat writes Real GDP for Q3 nicely positive, but long leading components mediocre to negative for the second quarter in a row

Robert Skidelsky writes Britain’s Illusory Fiscal Black Hole

Michael Hudson writes Gold as the Peace Currency

I bet you've never heard of Slovenia. It's the northernmost Balkan state, squeezed between Austria, Italy and Croatia on the Adriatic coast. It's small, peaceful (by Balkan standards) and prosperous compared to the rest of the Balkans, though that isn't saying much. It is also stunningly beautiful, in a mountains-and-lakes sort of way. It is in many ways rather like Austria.

But at the moment, Slovenia is famous not for its lovely scenery, or its important history, or its rich culture. No, it is famous for its banks. And not in a good way. Slovenia's banking crisis is a long-running sore.

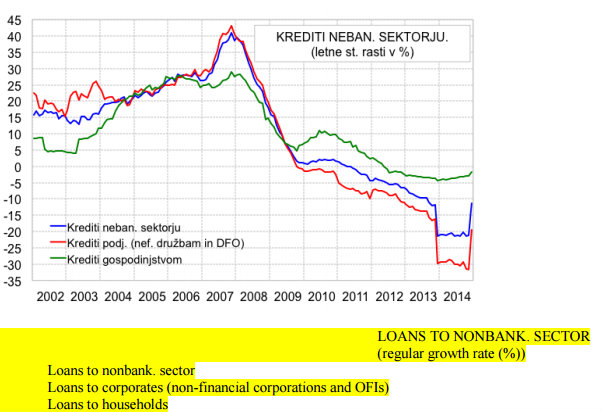

Slovenia's story is an all too familiar one. After it joined the EU in 2004, it entered the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM II) as a precursor to joining the Euro. EU membership requires free movement of capital across borders, and under ERM II its exchange rate was soft-pegged to the Euro. So it effectively lost control of monetary policy. The result, of course, was a mammoth inflow of foreign funds, a huge credit bubble, an enormous spike in real estate prices, and massive current account and fiscal deficits. This chart from a paper by the Bank of Slovenia on the causes of the banking crisis shows the buildup of credit from 2005 onwards, and in particular the strong spike in lending after Slovenia joined the Euro at the beginning of 2007:

Interestingly, in Slovenia the credit bubble seems to have affected corporations far more than households. And like most countries in Europe, the credit bubble burst at the end of 2007, not 2008.

You would think the bursting of the credit bubble would cause the greatest damage. But in Slovenia's case, the most harmful effects came from another source - the balance of payments. When you are locked into a currency union, a large and rising current account balance is dangerous. All it takes is a shock somewhere else in the world for investors to refuse to finance it - and because you cannot devalue and you have no control of monetary policy, investor flight forces a wrenching adjustment to the balance of payments, usually accompanied by widespread distress in the real economy and a rapid fall in GDP. This is what we call a "sudden stop". And this is what happened to Slovenia in 2008 when the financial crisis hit.

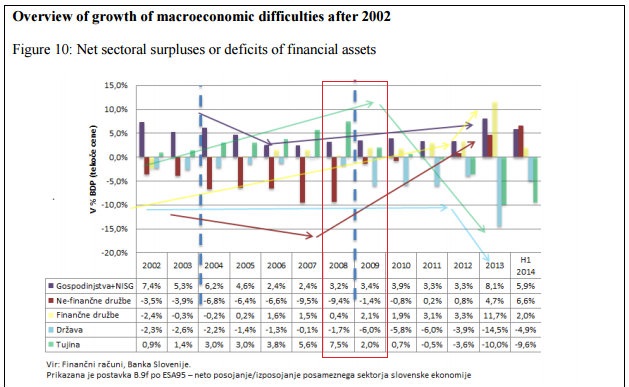

Here is the Bank of Slovenia's lovely chart of Slovenia's sectoral balances. You can see how the external balance (blue-green bars) rose from 2002 onwards and rapidly from 2007-08. When the financial crisis hit (box outlined in red) it abruptly switched from deficit to near-balance. At the same time, corporations rapidly deleveraged as the credit bubble burst (dark red bars). And the fiscal deficit (pale blue bars) surged from a perfectly reasonable 1.7% in 2008 to 6% in 2009. As a result of this, Slovenia was put into the EU's Excessive Deficit Procedure in November 2009.

The sharp-eyed among you will note that there is an even larger reversal between 2012-13. I shall return to this shortly. But for now, let's stick with 2008.

This table shows just how large the swings in investment and trade values were between 2008-9 (outlined in red):

Note that the balance of payments adjustment involved sharp falls in both imports AND exports, both goods and services. This fed through into a steep drop in GDP.

And this is what the investment reversal looked like, charted:

Ouch.The association between excessive bank lending, funded by cross-border investment flows, and Slovenia's sudden stop could hardly be clearer. But just in case anyone doesn't get it, the Bank of Slovenia spells it out:

The result of the fast growth of lending based on foreign borrowing by domestic banks and thus the increasing of the net debt of the Slovenian economy was increased vulnerability to financial shocks in the rest of the world, which materialised after the fall of Lehman Brothers in 2008.I want this statement to be framed and hung on the wall of every economics department, Treasury department and central bank in the world. Oh, and business schools, too, since tax-adjusted Modigliani-Miller has done more damage than almost any other theory, encouraging as it does high leverage and a preference for debt financing over equity. High debt levels increase economic fragility and vulnerability to shocks. That applies to corporations, households and governments alike.

Slovenia's problem was not public sector debt, which even after the crisis was low by EU standards at about 30% of GDP. It was private sector debt, particularly corporations and - later - banks. And the 2008 "sudden stop" clobbered its economy. The GDP fall of 7.9% in 2009 was one of the worst in the EU.

However, as the table shows, it bounced back quickly. The economy started to grow again in 2010 and exports recovered, although investment continued to decline due to the legacy of the financial crisis elsewhere in Europe. Balkan countries suddenly weren't attractive investment prospects any more.

Nevertheless, by 2012 Slovenia looked as if it was on the road to recovery. Yet within a year, it was back in recession and its banks were collapsing. What went wrong?

In fact, the recovery was an illusion. Slovenia's economy was in deep trouble: its banks were weak and under-capitalised, its corporations were suffering due to the slump in demand, and to crown it all it was being expected to impose a yearly fiscal tightening of 0.75% of GDP. Non-performing loans rocketed between 2008-12 as the weak economy took its toll on highly-indebted businesses:

Slovenian banks were already poorly capitalised, even by European standards. The rising NPLs ate the little capital they had, making an eventual state recapitalisation inevitable.And their funding situation was dire. They had been unable to fund themselves since the 2008 sudden stop when their foreign funding inflows dried up, and had became completely dependent on the sovereign for funding. It worked like this: the Slovenian government issued bonds, which were bought by its banks and then pledged to the Bank of Slovenia for Euro funding. It kept the banks alive, but at the cost of ever-growing sovereign and bank fragility. The inevitable sovereign credit downgrades followed in 2012 and 2013.

In December 2013, the ECB's stress test results revealed a total capital shortfall in the Slovenian banking sector of 4.8bn Euros (about 10% of GDP). The three largest banks failed the tests. On 18 December, the European Commission approved Slovenia's plan to inject $3.2bn Euros of new capital into its banks and transfer non-performing loans into a new "bad bank", the Bank Asset Management Company (BAMC), Junior bondholders were forced to take a haircut of an estimated 600m Euros, and shareholders were wiped.

The junior bondholders - and even the shareholders - fought this bail-in tooth and nail. The Slovenia Times reports that the Slovenia Constitutional Court "admitted several applications" by subordinated bondholders to have the bail-in overturned. The Constitutional Court referred the matter to the European Court of Justice. This week, the ECJ gave its judgment. And the judgment has resolved - well, absolutely nothing.

The case hung on the interpretation of a Communication from the European Commission in 2013 which established the ground rules for the granting of state aid for banks in the financial crisis. This is known as the Banking Communication. The ECJ decided that the Banking Communication "must be interpreted as meaning that it is not binding on the Member States."

Bondholder representatives were delighted:

We are very satisfied with the ruling," said Mr. Kristjan Verbic, President of VZMD. "VZMD and Better Finance - The European Federation of Investors and Financial Services Users consider this decision to be a victory for investors. The European Court of Justice ruled that 'expropriations of and encroachment upon shares and bonds of Slovenian banks were neither necessary nor unavoidable for the restructuring of the banking system and allocation of state aid.' VZMD has maintained this was the correct analysis since the very beginning."No doubt they will now go back to the Slovenia Constitutional Court and petition for the bail-in to be overturned, with the backup of an appeal to the European Court of Human Rights if the Constitutional Courts slaps them down.

But I fear they are wrong. The Banking Communication does not impose a requirement on Slovenia to bail in subordinated creditors and shareholders, but it doesn't prevent it from doing so, provided that the bail-in doesn't exceed what is necessary to overcome the banks' capital shortfall and doesn't leave creditors in a worse position than they would have been in had the bank failed. Indeed, as the judgment goes out of its way to emphasise that the Banking Communication provides for shareholders and subordinated debt holders to share in the losses from a failing bank, it is hard to see any reason for the bondholders to rejoice. Unless they can show that bail-in was either unnecessary or discriminatory, they still have no case.

And Slovenia can't possibly afford the cost of overturning the bail-in, anyway. Three years on, Slovenia is still in a mess. The bank bailout raised the government deficit to 15% and public debt/GDP to 71%, and Slovenia additionally suffered a brutal recession: even now, GDP growth remains well below 1% and unemployment is above 11%. Fiscal consolidation under the Excessive Deficit Procedure has brought its fiscal deficit down below 3%, but at the end of 2015, Slovenia's debt/GDP was 83% of GDP.

The IMF has just completed its latest Article IV consultation, and the principal findings are worrying. It appears that, expensive though it was, the bank restructuring was insufficient to restore normal credit conditions. Non-performing loans remain high, and bank lending is still contracting despite falling interest rates and looser credit conditions. Partly, this is due to low credit demand, especially among smaller companies, many of which are still highly indebted and struggling to meet their obligations. The truth is that Slovenia's supply side has taken a terrible hit, and recovery is proving very slow and painful.

So what lessons should we draw from this?

Firstly, that relinquishing control of monetary policy by opening the capital account and fixing the exchange rate carries a terrible price. The Bank of Slovenia lays the responsibility for the 2004-8 credit bubble primarily at the door of the ECB, whose interest rate policy was too loose for Slovenia at that time. But the ECB had to consider the Eurozone as a whole, and Germany at that time was in the doldrums. Interest rates were inevitably lower than the overheating Slovenia needed. Slovenia is by no means the only Eurozone country with this problem. It may be that in the future, movement of capital in the Eurozone will have to be moderated to prevent the large destabilising capital flows that have caused so much damage over the last decade.

And secondly, that banks MATTER. Unless fiscal finances are very stretched, as in Greece, repairing banks should be a far higher priority than repairing fiscal finances. Repairing the banks early reduces the damage to the economy that a wrecked banking sector causes, and restoring bank lending can restore growth quickly and effectively, as Latvia's remarkable recovery showed. This can help restore fiscal finances without the need for years of painful consolidation.

When researching this piece, I was struck by how little attention was paid to the state of the banking sector until it was far too late. The Bank of Slovenia comments that the Slovenian government did not take action to recapitalise its banks in 2008-11 when it should have done. But the IMF conducted two Article IV reviews during that time. And Slovenia was in the Excessive Deficit Procedure throughout that time, under regular supervision from the European Commission. The primary focus of both the IMF and the EC was on fiscal finances, and the IMF additionally did a "special issues" report in May 2009 that focused on inflation - yes, inflation, in a country which was in deep recession. Throughout all of this, the looming implosion of the banks appears to have gone almost unnoticed. If these august institutions don't take any notice of banks and their crucial role in making or breaking an economy, why on earth should we expect governments to?

Related reading:

Property, inequality and financial crises

How do you say "dead cat" in Latvian?

A Finnish cautionary tale

Black Thursday

Image from www.smarteuropetravel.com