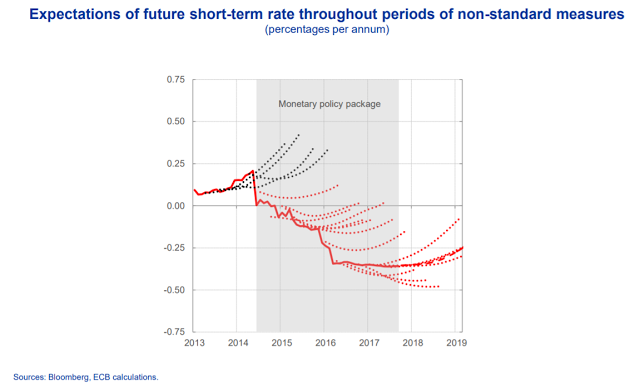

In a speech in London the other day, Peter Praet discussed the ECB's unconventional policy measures. I was there, and I have to say that he deviated considerably - and rather entertainingly - from the version of the speech on the ECB website. But his core message was still the same: "Rates are expected to remain at their present levels for an extended period of time, and well past the horizon of our net asset purchases. So, no interest rate hikes for a long time to come.But that's not what his final chart says: Market expectations are that interest rates will start to rise any day now. And no, this is not expectations of rate rises due to the end of QE, which the ECB has arguably signalled for early 2018 (or at least it didn't signal that it wouldn't end then). This is the short-term

Topics:

Frances Coppola considers the following as important: central banks, Interest rates, QE

This could be interesting, too:

Merijn T. Knibbe writes Monetary developments in the Euro Area, september 2024. Quiet.

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Central bank independence — a convenient illusion

Merijn T. Knibbe writes How to deal with inflation?

Matias Vernengo writes Sharing Central Banks’ costs and profits of monetary policy in the euro area

"Rates are expected to remain at their present levels for an extended period of time, and well past the horizon of our net asset purchases.So, no interest rate hikes for a long time to come.

But that's not what his final chart says:

Market expectations are that interest rates will start to rise any day now. And no, this is not expectations of rate rises due to the end of QE, which the ECB has arguably signalled for early 2018 (or at least it didn't signal that it wouldn't end then). This is the short-term rate, which is not directly affected by QE. Admittedly, future expectations of short-term rates in 2018 and beyond are close to the ECB's own predictions. But is that because markets believe the ECB's forecasts, or because the ECB has fitted its forecasts to market expectations? Or are they just convergent, for now? If so, will they remain convergent?

Mind you, markets have been expecting rate rises "any day now" for years. If ever there were evidence of the irrationality of markets, this chart is it. They have repeatedly anticipated rate rises since 2014 - except briefly during the 2016 deflation and the start of "lower for longer" forward guidance, when they expected rate cuts. Neither rate rises nor rate cuts ever materialised.

The counter to "markets will only be guided in the direction in which they were going anyway" is "central banks are not tame lions". It is an open question which is more powerful. On the one hand, markets form their own view of where they think rates are going, and expect the ECB to fall into line. On the other hand, the ECB determinedly refuses to do what markets expect. This is a credit to its independence - after all, a central bank that simply does what markets expect has no more real independence than a central bank that simply does what politicians tell it to.

But it also shows that the ECB has a credibility problem. Markets don't believe it: forward guidance is still "lower for longer", but markets are pricing in imminent rate rises. For how long will markets take any notice at all of forward guidance? At what point will the ECB be forced to raise rates simply because it has cried "wolf" too often? It was, after all, forced to commence QE for exactly this reason. With hindsight, markets were right - QE has been hugely successful in supporting aggregate demand in the depressed Eurozone. But that doesn't exactly engender confidence in the ECB.

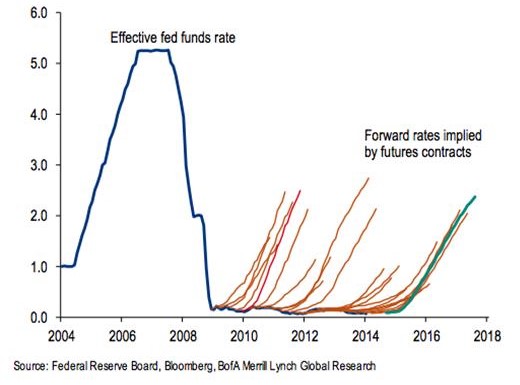

The ECB is not the only central bank with a market credibility problem. Here is the same chart for the Fed (courtesy of the Fiscal Times):

This one is a couple of years old, of course - but then the Fed is further on in the cycle. The same pattern is evident. Markets expected interest rates to be raised far sooner and more quickly than the Fed has actually raised them. Had the Fed done what markets expected in 2015, the Fed Funds rate would now be well over 2%. If the Fed had done what markets expected in 2010 - well, who knows where rates might be now?

This raises a difficult question. Currently, the Fed is signalling a rate rise in December and further rate rises next year. But markets don't believe it. Inflation is stubbornly below target, and although jobs figures are good, wage growth is not. Markets are pricing in maybe one rate rise next year, not three. Who has this right - the Fed, or the markets? And if the Fed goes ahead with rate rises that markets regard as unjustified, what will be the consequences, not only economically, but for the Fed's credibility? If the result is an economic downturn, it is hard to see that the Fed would not be blamed.

The Bank of England has a similar problem. It too has a history of disappointing markets (chart courtesy of Economics Help):

Again, this is a couple of years old, which is just as well since events in 2016 totally upset the applecart. Far from raising the base rate, the Bank of England cut it by 25 bps in August 2016. Ever since, there has been continual discussion about whether this was the right move and when it should be reversed. So severe has been the criticism of the Bank of England in some quarters that at one stage it threatened the tenure of the Governor, Mark Carney, and raised questions about the Bank's independence.

Currently, the Bank of England is signalling a rate rise in November. This might only amount to reversing the 25bps cut last year, but it could be regarded as the start of a tightening cycle, especially as inflation is forecast to rise further and remain above target until 2019. Markets have already priced in this rate rise. Yet the economic outlook for the UK is increasingly gloomy, with both consumer and business confidence declining and weak PMI indexes. As with the US, jobs are holding up, but wage growth is disappointing and - importantly - because of the UK's relatively high inflation, real wages are falling. There are also signs of a downturn in the housing market, which in the UK is often a leading indicator of a recession.

So, suppose the MPC looks at all this worrying stuff and decides not to go ahead with a rate rise in November? How will markets respond to their expectations being disappointed yet again?

Or - alternatively - if the MPC goes ahead with a rate rise anyway despite the poor prognosis, and the UK suffers an economic downturn, what would that do to the Bank of England's credibility? As with the Fed, it is hard to see that it would not be blamed for raising rates just as the business cycle turned.

This brings me back to Peter Praet's signal that rates in the Eurozone will continue to remain low for the foreseeable future. Such a statement in an official speech from a central banker is forward guidance. Is the ECB trying to avoid the cleft stick that both the Fed and the Bank of England appear to be in?

But by signalling "lower for longer" for the foreseeable future, the ECB potentially falls foul of a different problem. Of the four big central banks (excluding PBOC, which is a law unto itself), the only one that doesn't have a pattern of dashed hopes of rate rises is the Bank of Japan. Sadly, though, this is not an indicator of credibility. The Bank of Japan would love to get interest rates off the zero lower bound where they have been sitting for two decades. But no-one believes it will ever get inflation high enough to justify raising them.

The ECB, too, is battling stubbornly low inflation, and like Japan, the Eurozone population is ageing fast. As Japan's experience shows, raising inflation is hard to do when the demographics are against you: older people don't borrow to spend as younger ones do, and they may have high savings rates due to the need to ensure they have sufficient money for their retirement.

There is another potential reason why the ECB may be forced to keep rates "lower for longer" for the foreseeable future. Concurrent fiscal and monetary tightening causes deflation (see the UK in the 1920s, or Germany in the early 1930s), and the Eurozone's fiscal compact keeps fiscal policies tight across the entire zone. The ECB is therefore forced by the fiscal position to keep monetary policy loose. Personally I would call this fiscal dominance, which might seem strange given the ECB's famous "independence". But if tightening monetary policy would cause deflation because of a persistently over-tight fiscal position, the ECB has no real choice but to compensate with monetary policy, does it?

Markets know this, and that is why they effectively forced the ECB to do QE. They are now pricing in rate rises because the Eurozone is recovering, even though the Eurozone's fiscal position remains tight, its population isn't getting any younger and there are as yet no signs of any resurgence of inflation. It looks to me as if the ECB is trying to discipline markets into accepting lower interest rates than they think are justified. The trouble is, that because the ECB previously did what markets wanted, they will expect it to do so again.

It is important that the ECB does not give in this time round, and that the Fed and the Bank of England win their battles with markets, too. Central banks' credibility problem is potentially costly. It is far better for markets to be wrong than central banks. True, market participants can lose a lot of money from wrong positioning: some of them may even go out of business. But when central banks get it wrong, the entire economy feels the effect - and the end of independence is not far away.

Related reading:

Forward Non-Guidance - Forbes