Coronavirus is scaring the world. Last weeks' stock market crash was the worst since 2008. And yields on safe assets, especially U.S. Treasuries, are crashing as investors dump anything they see as remotely risky. I suppose if you fear sudden death, you want your assets to be safe - though I sometimes wonder if investors understand that you can't take them with you.Anyway, central banks are of course responding to the market panic. The Fed has just announced a 50 basis points cut in interest rates. Here's the FOMC's mercifully brief statement in full (my emphasis): The fundamentals of the U.S. economy remain strong. However, the coronavirus poses evolving risks to economic activity. In light of these risks and in support of achieving its maximum employment and price stability goals, the

Topics:

Frances Coppola considers the following as important:

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Vienneau writes Austrian Capital Theory And Triple-Switching In The Corn-Tractor Model

Mike Norman writes The Accursed Tariffs — NeilW

Mike Norman writes IRS has agreed to share migrants’ tax information with ICE

Mike Norman writes Trump’s “Liberation Day”: Another PR Gag, or Global Reorientation Turning Point? — Simplicius

Coronavirus is scaring the world. Last weeks' stock market crash was the worst since 2008. And yields on safe assets, especially U.S. Treasuries, are crashing as investors dump anything they see as remotely risky. I suppose if you fear sudden death, you want your assets to be safe - though I sometimes wonder if investors understand that you can't take them with you.

Anyway, central banks are of course responding to the market panic. The Fed has just announced a 50 basis points cut in interest rates. Here's the FOMC's mercifully brief statement in full (my emphasis):

The fundamentals of the U.S. economy remain strong. However, the coronavirus poses evolving risks to economic activity. In light of these risks and in support of achieving its maximum employment and price stability goals, the Federal Open Market Committee decided today to lower the target range for the federal funds rate by 1/2 percentage point, to 1 to 1‑1/4 percent. The Committee is closely monitoring developments and their implications for the economic outlook and will use its tools and act as appropriate to support the economy.So no resumption of QE, as yet. But we should remember that the Fed is currently providing copious liquidity to the dollar repo market. Today, it bought $7,499 billion of Treasury bills. This appears extremely generous, to say the least - but the offer was three times oversubscribed. Clearly, the market would like more liquidity. Much more. There's a whopping panic going on, which is driving investors into safe assets and cash. If it continues, the Fed might step up purchases. That's what it means by "will use its tools and act as appropriate to support the economy."

The Fed's decision follows on from the Bank of Japan's announcement, which also promises lots of support for panicking investors:

Global financial and capital markets have been unstable recently with growing uncertainties about the outlook for economic activity due to the spread of the novel coronavirus. The Bank of Japan will closely monitor future developments, and will strive to provide ample liquidity and ensure stability in financial markets through appropriate market operations and asset purchases.Also today, the People's Bank of China, which has been dealing with market panic for a while now, has gone into some detail about its recent actions:

First, the PBC has enhanced operations of open market reverse repos, and managed to guide the rates of reverse repos, the bid rates of medium-term lending facility (MLF) and the loan prime rate (LPR) lowered by 10 basis points successively, which drove down the overall market interest rates. The measures have played a crucial role in maintaining market liquidity and the stability of the financial markets after they reopened following the Spring Festival. So far, such short-term liquidity has largely been withdrawn, and the liquidity of the banking system remains reasonably adequate.

Second, the PBC has set up RMB300 billion of special low-cost central bank lending to major national banks and certain local incorporated banks in 10 key provinces (municipalities), including Hubei, to support enterprises directly involved in the combat against the epidemic in a targeted manner.And Australia's central bank cut interest rates by 25 basis points, citing a slowing economy as well as the adverse impact of coronavirus:

The global outbreak of the coronavirus is expected to delay progress in Australia towards full employment and the inflation target. The Board therefore judged that it was appropriate to ease monetary policy further to provide additional support to employment and economic activity. It will continue to monitor developments closely and to assess the implications of the coronavirus for the economy. The Board is prepared to ease monetary policy further to support the Australian economy.The Bank of England, describing its responsibility as being to "help UK businesses and households manage through an economic shock that could prove large but will ultimately be temporary," said it would "take all necessary steps to support the UK economy and financial system, consistent with its statutory responsibilities." Mark Carney, the outgoing Governor, hinted to MPs that the Bank could cut interest rates at the next meeting, and that capital requirements for banks might be adjusted to protect against inadvertent credit tightening for companies suffering from disrupted cash flows.

Meanwhile, the Indian central bank, also "standing ready" to do whatever it takes to keep the show on the road, is looking for coordinated global action:

Globally, financial markets have been experiencing considerable volatility, with the spread of the coronavirus triggering risk-off sentiments and flights to safe haven. Spillovers to financial markets in India have largely been contained. Growing hopes of coordinated policy action to mitigate a broader fallout to economic activity has boosted market sentiment today. The Reserve Bank of India is monitoring global and domestic developments closely and continuously and stands ready to take appropriate actions to ensure orderly functioning of financial markets, maintain market confidence and preserve financial stability.They might even get it. Fed's chief Jay Powell seems rather keen on coordinated action too.

And what about the ECB? The Eurozone economy is in pretty bad shape. Inflation is stubbornly below target, growth is pathetic, and the global trade slowdown threatens the export-led growth model of its core economies, particularly the mighty Germany. Surely, if any central bank were going to take decisive action to ward off an economic slump, it would be the ECB?

Nope. They are worrying about inflation:

The coronavirus outbreak is a fast developing situation, which creates risks for the economic outlook and the functioning of financial markets. The ECB is closely monitoring developments and their implications for the economy, medium-term inflation and the transmission of our monetary policy. We stand ready to take appropriate and targeted measures, as necessary and commensurate with the underlying risks.Seriously, guys?

To be fair, the ECB is already doing QE, and its deposit rates are negative. But the difference between the expansionary tone of other central banks and the ECB's dour comments is notable. Something tells me the ECB doesn't really want to do any more. Christine Lagarde, the new ECB President, has made her preference for coordinated fiscal loosening abundantly clear. Sitting on her hands over coronavirus just might be her strategy for forcing the austere governments of Germany and the Netherlands to remove their hair shirts and apply some emollient.

The ECB has reason to be cautious. A serious question needs to be answered about what role central banks should play in this crisis. We have become used to relying on central banks to prop up the economy when it is hit by a shock such as a financial crisis. But this is not the same sort of shock. A financial crisis is an endogenous shock which disrupts both supply and circulation of money in the economy, triggering sharp falls in spending and investment: damage to the supply side is secondary to, and consequent on, this collapse of aggregate demand. Central banks are well equipped to deal with this sort of shock, though in the last decade they have not always used their tools effectively. But the effect of the coronavirus is to lay workers low, force firms to close, and disrupt supply chains. It is thus an exogenous shock principally affecting the productive capacity of the economy. I hate to be a Cassandra, but injecting large amounts of money into an economy when production is falling sharply due to factors beyond the central bank's control is a recipe for high inflation.

Nonetheless, there are actions that central banks can usefully do to limit the damage to the economy from this sort of shock. Supporting businesses suffering from supply disruption, for example. "We don’t want viable businesses to go out of business because of the very necessary steps that need to be taken to protect and serve the British public,” Mark Carney told MPs. He went on to draw a nice distinction between temporary disruption to the supply side and permanent impairment of it.

Distinguishing between temporary and permanent changes is crucial for central banks. Central banks can offset temporary disruption to financial flows due to supply-side shocks. But they can't by themselves prevent such a shock doing permanent damage, or repair the damage once it has occurred. That responsibility falls to governments.

Unfortunately, governments don't seem to want this responsibility. President Trump, for example, seems only too keen to pass the buck to the Fed. And he's not the only one. You would think that governments would respond with "shock and awe" to the threat of a global pandemic. But so far, their responses have been distinctly underwhelming. At FT Alphaville, an exasperated Claire Jones depicted the Group of Seven's announcement yesterday as a bun with no burger. She had a point. There was absolutely no substance to it:

We, G7 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors, are closely monitoring the spread of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and its impact on markets and economic conditions.

Given the potential impacts of COVID-19 on global growth, we reaffirm our commitment to use all appropriate policy tools to achieve strong, sustainable growth and safeguard against downside risks. Alongside strengthening efforts to expand health services, G7 finance ministers are ready to take actions, including fiscal measures where appropriate, to aid in the response to the virus and support the economy during this phase. G7 central banks will continue to fulfill their mandates, thus supporting price stability and economic growth while maintaining the resilience of the financial system.

We welcome that the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and other international financial institutions stand ready to help member countries address the human tragedy and economic challenge posed by COVID-19 through the use of their available instruments to the fullest extent possible.

G7 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors stand ready to cooperate further on timely and effective measures.”Pathetic.

The problem is that since the financial crisis, the boundary between monetary and fiscal policy has become so blurred that the limits of central bank responsibility are no longer clear. Instead of saying "maybe they shouldn't be doing this", some people are intent on finding central banks new tools so that they can offset any sort of shock without governments having to get involved. Others are so exasperated with what they see as the failure of central banks that they want to hand everything over to fiscal authorities. Failure to establish clear roles for central banks and fiscal authorities in the aftermath of the financial crisis, and ever-increasing reliance on central banks to keep economies afloat under all circumstances, is now coming back to haunt us.

Cutting interest rates and injecting liquidity into markets may prevent a supply-side shock morphing into a financial crisis, and easing credit conditions may help to limit bankruptcies and job losses. But it won't help the people who will suffer from coronavirus. And although helicopter money would help raise output when the crisis over, at this stage it is the wrong medicine. What people need right now is high quality free healthcare when they are ill, generous income support when they are unable to work due to self-isolation or job loss, and maintenance of essential food and other supplies. And non-financial firms need government guarantees and cash flow support. It is not the role of central banks to provide these emergency services to the population. It is the job of governments.

So although the ECB can and should do more to support the ailing Eurozone economy, Christine Lagarde's stance on fiscal policy is right. Governments need to stop expecting central banks to do the heavy lifting. They must don their hard hats and steel toecaps, and prepare to get their hands - and their budgets - very dirty indeed.

Related reading:

Dissecting the Eurozone's (lack of) inflation

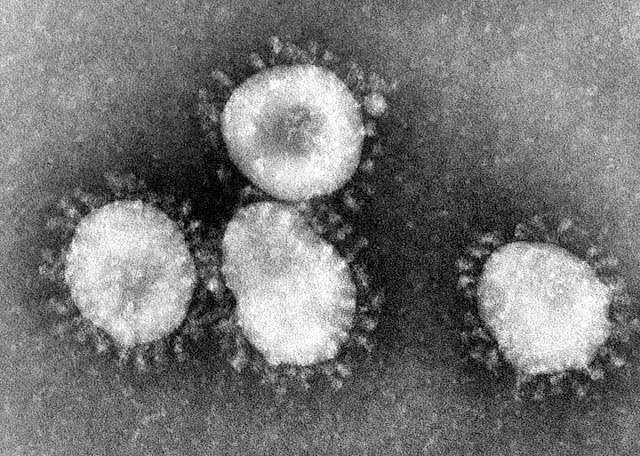

Electron microscope image of coronaviruses from Wikipedia.