Here are some things I think I am thinking about: 1) Are we on the verge of a recession? My theory about the COVID recession is that it wasn’t really a recession in the traditional boom/bust sense. It was more like a natural disaster or an exogenous shock to the economy because of the way the government shutdown so much of the economy. It was a self imposed recession as opposed to some naturally developing boom/bust. Then the government responded with unprecedented stimulus, the economy snapped back very quickly and that took the boom part of the cycle to its inevitable speculative peak. If you use annualized data the 2010-2021 boom looks like one big long cycle with a huge blow off at the end. That set the stage for a very fragile economic environment. Booms can cause busts when the

Topics:

Cullen Roche considers the following as important: Most Recent Stories

This could be interesting, too:

Cullen Roche writes Understanding the Modern Monetary System – Updated!

Cullen Roche writes We’re Moving!

Cullen Roche writes Has Housing Bottomed?

Cullen Roche writes The Economics of a United States Divorce

Here are some things I think I am thinking about:

1) Are we on the verge of a recession?

My theory about the COVID recession is that it wasn’t really a recession in the traditional boom/bust sense. It was more like a natural disaster or an exogenous shock to the economy because of the way the government shutdown so much of the economy. It was a self imposed recession as opposed to some naturally developing boom/bust. Then the government responded with unprecedented stimulus, the economy snapped back very quickly and that took the boom part of the cycle to its inevitable speculative peak. If you use annualized data the 2010-2021 boom looks like one big long cycle with a huge blow off at the end.

That set the stage for a very fragile economic environment. Booms can cause busts when the booms are based on fragile underlying currents. You could argue that a lot of things that were going  on in 2021 were unsustainable speculative undercurrents. While Russia attacking Ukraine is also an exogenous shock the economy is likely to respond in a much more “natural” manner to this. But what will that response look like? No one really knows, but some broader indicators don’t bode well.

on in 2021 were unsustainable speculative undercurrents. While Russia attacking Ukraine is also an exogenous shock the economy is likely to respond in a much more “natural” manner to this. But what will that response look like? No one really knows, but some broader indicators don’t bode well.

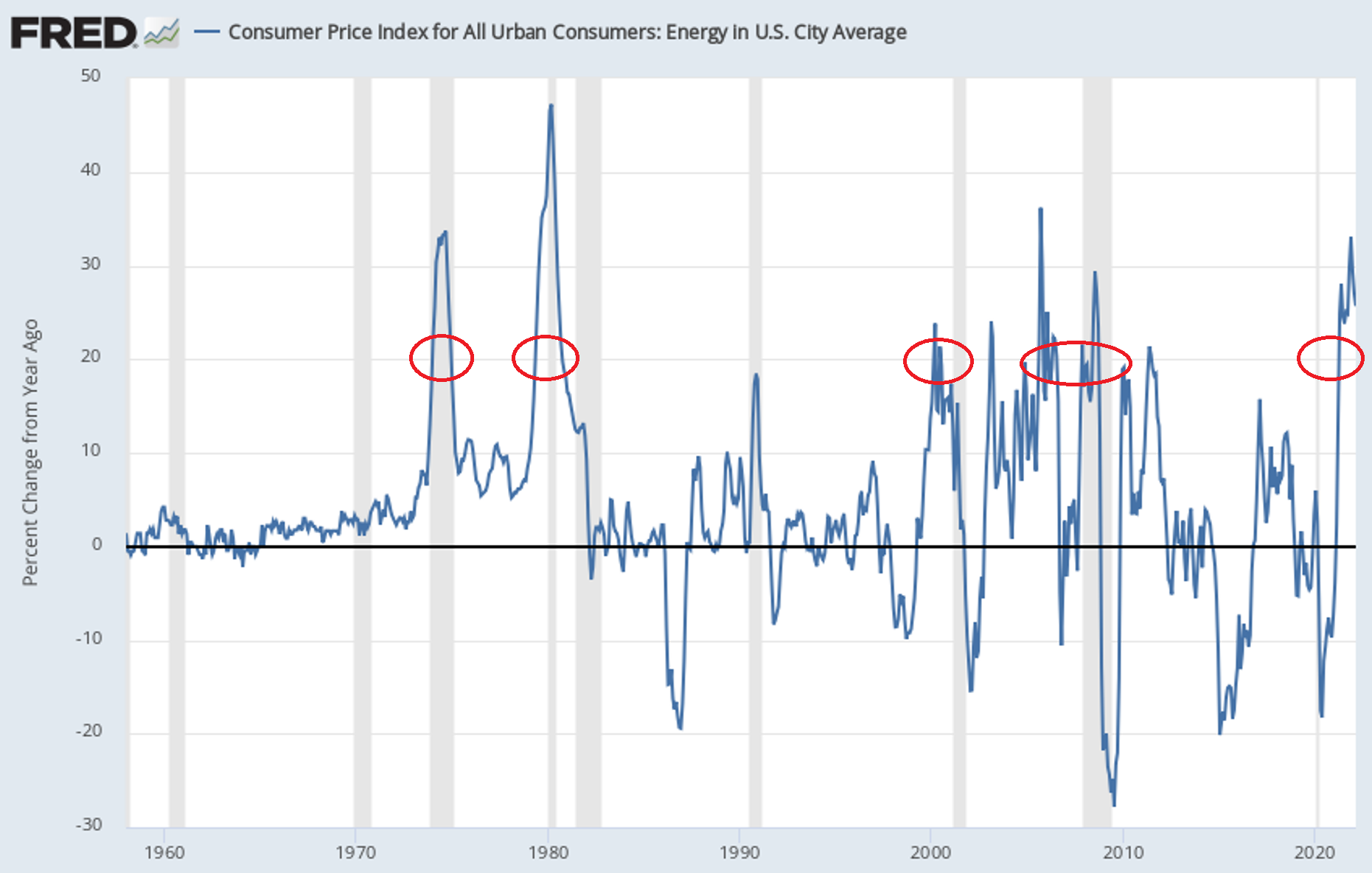

Two indications that are worrisome are energy price surges and the flattening yield curve. And both are pointing to a high probability of a recession. Energy prices are interesting mainly because the Fed likes to strip out energy prices to get a smoother understanding of inflation. This makes sense, but it also exposes the Fed to the risk of misunderstanding when energy prices are creating major economic imbalances. If you subscribe to the boom/bust theory of recessions then the current surge in energy prices are causing a shock and could resolve in a sort of plucking effect in the way that “the cure for high prices is high prices”. That is, high commodity prices shock consumers and cause them to tighten up thereby resulting in a decline in prices.

You could argue that the Fed’s interpretation of something like this is exactly wrong in that they will tend to see high energy prices as a need to tighten, but by the time they get the data to confirm their rate hikes the damage has already been done. The time to raise rates is BEFORE the price surge, not after it. As I said back in 2020, I expected inflation to surge following the huge stimulus and that the Fed would be chasing its own tail to raise rates. Well, they’re chasing their tail again here and now they’re on the verge of inverting the yield curve and tightening financial conditions at a time when energy prices are already tightening the economy.

None of this is good and I am about as uncomfortable about recession risk as I can remember being in a long time.

2) Spinning the inflation narrative.

The White House put out a press release last week claiming that inflation was due to Putin. Sigh. Why do people have such a hard time being objective about things and being transparent about cause/effect? We ran $7T deficits for 2+ years and locked down the economy. Yes, there were supply constraints. And yes, the Putin commodity price surge is going to cause continued high inflation. But we should also admit that big fiscal deficits caused inflation in the past. It was a calculated risk during a terrible pandemic. But instead of recognizing this we seem to be trying to claim that government spending didn’t contribute to this.

This is a dangerous narrative in my view. Look, I am by no means against countercyclical government spending. But we should be willing to admit that it can be overdone and was overdone. This is how we learn from the past and avoid making the same mistake in the future. Accountability is a super power. Unfortunately, too many politicians are missing that super power.

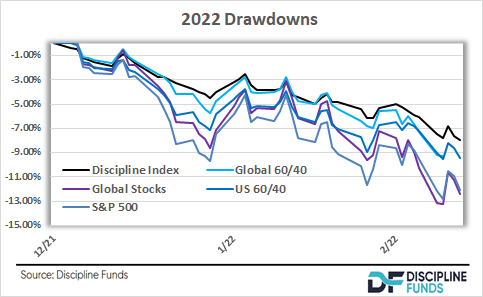

3) Is 60/40 Finally Dead?

Global 60/40 is down -9.1% in 2022 while US 60/40 is down -9.4%. It has a lot of people asking if 60/40 is dead? There is a good deal of hyperbole in these discussions. After all, saying a  stock/bond portfolio is “dead” implies that both stocks and bonds will perform terribly in perpetuity. Which is just wrong. I have no doubt that global corporations will continue to make innovative products and earn profits in the long-run. And the arithmetic on bonds is about as easy as it gets – an investment grade bond portfolio will earn about 3% per year if you hold that portfolio for 5+ years. Stocks and bonds aren’t dead by any means. But they don’t look as vibrant as they have in the past.

stock/bond portfolio is “dead” implies that both stocks and bonds will perform terribly in perpetuity. Which is just wrong. I have no doubt that global corporations will continue to make innovative products and earn profits in the long-run. And the arithmetic on bonds is about as easy as it gets – an investment grade bond portfolio will earn about 3% per year if you hold that portfolio for 5+ years. Stocks and bonds aren’t dead by any means. But they don’t look as vibrant as they have in the past.

In my view it’s better to understand that 60/40 isn’t always the same even though its allocation always looks the same. For instance, a 60/40 in 1980 had a vastly different return profile than a 60/40 in 2020 because the bonds in 2020 cannot produce nearly the same risk adjusted returns in the next 40 years that they have in the past 40 years. And history confirms this. A 60/40 from 1940-1980, when rates were near 0% and rose to 10%+, was a vastly worse risk adjusted returning portfolio than the portfolio from 1980-2020. But even in the 1940-1980 period the 60/40 still generated 8.5% per year. Not bad at all. The problem is, this portfolio generated lower returns than the 1980-2020 portfolio AND did so with greater volatility.

So, I think the key point here is understanding that 60/40 isn’t necessarily dead, but is likely to generate worse risk adjusted returns going forward.