Another brick in the wall .[embedded content] We live in an unequal society where inequality is increasing in many areas, especially regarding income and wealth. The differences in living conditions for different groups, in terms of class, ethnicity, and gender, are unacceptably large. In the world of education, family background still has a significant impact on pupils’ performance, and it becomes even more pronounced as they get older. It cannot be seen as anything other than a colossal failure when a school with compensatory aspirations shows a pattern where parents’ educational backgrounds have an increasing impact as the pupil gets older. Contrary to all the promises of reform pedagogy, it is primarily children from families without academic

Topics:

Lars Pålsson Syll considers the following as important: Education & School

This could be interesting, too:

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Open letter to my students

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Svensk universitetsutbildning — ett skämt!

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Evidensmonstret i svensk skola

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Lärarutbildningarnas haveri

Another brick in the wall

.

We live in an unequal society where inequality is increasing in many areas, especially regarding income and wealth. The differences in living conditions for different groups, in terms of class, ethnicity, and gender, are unacceptably large.

In the world of education, family background still has a significant impact on pupils’ performance, and it becomes even more pronounced as they get older. It cannot be seen as anything other than a colossal failure when a school with compensatory aspirations shows a pattern where parents’ educational backgrounds have an increasing impact as the pupil gets older.

Contrary to all the promises of reform pedagogy, it is primarily children from families without academic traditions who have lost out in the shift in the perception of school that has taken place in the past half-century. Today, with school vouchers, free school choice, and charter schools, the development has only further strengthened the opportunities of highly educated parents to control their children’s schooling and future, contrary to all the compensatory promises. It is difficult to see who, with today’s schools, will be able to make the ‘class journey’ that so many in my generation have made.

Contrary to all the promises of reform pedagogy, it is primarily children from families without academic traditions who have lost out in the shift in the perception of school that has taken place in the past half-century. Today, with school vouchers, free school choice, and charter schools, the development has only further strengthened the opportunities of highly educated parents to control their children’s schooling and future, contrary to all the compensatory promises. It is difficult to see who, with today’s schools, will be able to make the ‘class journey’ that so many in my generation have made.

The school plays a large and important functional role in the reproduction of the labor market and socialization-related discipline in our society.

All of this is well known, but everything has its time and place. What I want to address here is something else. Socialization theory and hermeneutics complement each other. Instead of explaining, I am here more interested in understanding. Instead of the school’s societal functions, I focus here on some cultural and subjective theoretical aspects of the school as an institution. I want to present some sketchy thoughts on a specific question complex. How should the school be related to society at large? What can and should the school do and be?

We now live in a society where identity is something created rather than, as in the past, something inherited. This can be experienced both as a liberation and as a burden. Many young people today experience ambivalence toward the freedom that the detraditionalization of our social lives has brought. This is also expressed to a high degree in school. Much of the orientation problems that young people express are related to the norm and value dissolution that the pervasive transformation of modern social life has led to. In the past, one’s social identity was more clearly defined by an inherited social identity. Today, the image that young people have of life is much more about what they, as individuals, want to do with their lives. Each individual creates their own identity. But this also means that the support to lean on is not there. There is ‘free’ movement under one’s own responsibility and one’s own anxieties and rootlessness.

When yours truly grew up and went to school in the 1960s and 1970s, there was still a fairly clear demarcation line between the school, which took care of our cognitive skills, the family, which took care of the upbringing and emotional needs of the growing generation, and society at large.

What was once new becomes old. The rebellion of reform pedagogy against a fossilized school institution with its outdated norms and teaching styles was new and radical in the 1970s. Today, reality has surpassed it. When everyone already perceives themselves as doing as they please and basing their actions on their own experiences and lives, it is no longer radical to say to students: “Do as you please.” The answer is often, “Can’t we avoid having to do as we please? We already do so much of that in our daily lives and in modern schools. It no longer gives us an emancipatory experience. It’s just more of the same slack and indifferent …”

The innovative power of de-formalization and subjectification has long since exhausted its potential. Therefore, it is hopelessly outdated to demand increased informality, closeness, and subjectivity in today’s schools. To some extent, starting from the pupils’ reality must not be synonymous with fully adopting and embracing it. On the contrary, one must present a counter-image, an alternative. Not identity, but difference.

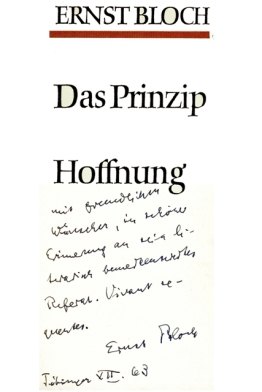

The school should teach for a life other than the one that exists in school. Above all, it should ensure that each pupil’s potential to live a different life from the one they are living today is fully realized. When continuity, stability, and traditions lose their significance and self-legitimizing aura, this becomes even more important. The school must cultivate ‘the principle of hope.’ Without the future-oriented hope of a better world, the school cannot fulfill its task. Therefore, socialization-theoretical explanations regarding the question “how one has become who one is” cannot be the starting point. In the school world, the educational-theoretical question “how one can become what one has the potential to become in the future” must be the guiding starting point.

The school should teach for a life other than the one that exists in school. Above all, it should ensure that each pupil’s potential to live a different life from the one they are living today is fully realized. When continuity, stability, and traditions lose their significance and self-legitimizing aura, this becomes even more important. The school must cultivate ‘the principle of hope.’ Without the future-oriented hope of a better world, the school cannot fulfill its task. Therefore, socialization-theoretical explanations regarding the question “how one has become who one is” cannot be the starting point. In the school world, the educational-theoretical question “how one can become what one has the potential to become in the future” must be the guiding starting point.

Today, when the lifeworld, everyday life, and subjectivity are fully embraced in the school world, more of the same is not needed. Reform pedagogy has been so successful that it is now falling on its own grip. Subjectification has long since reached the saturation point, and saturation has led to negative marginal utility. The euphoria of novelty has turned into the discomfort of over-saturation. It is no longer helpful to invoke phrases from another time — a non-saturated time — where these demands may have seemed emancipatory. Today, the response from pupils is usually only: “We’ve been there. We’ve seen that. We’ve done that. Point to something that goes beyond ourselves and allows us to grow instead!” What was the highest radicalism in the 1970s when yours truly studied at the teacher training college – “start from your own interest in bikes and write the history of technology based on that” – today has only a glimmer of laughter. When everyone already writes their “bike history”, something else is needed.

Distance and separation provide perspective. The school should be an island in a sea of societal routines. Insisting that the school should continue to approach the pupils’ experiential horizons is no longer viable. The school cannot be a reality TV world where people expose their private and intimate lives to satisfy exhibitionistic self-affirmation impulses. Today, we do not need more leveling between the pupils’ lifeworld and the school. On the contrary, we need more respect for the necessary difference between these worlds. Learning in school must acknowledge, as a starting point, the difference between the pupils’ lifeworld and the school itself in order to function as a forward-looking bridge.

School is not society or family. The school should not be an extension of the pupils’ lives outside of school. On the contrary, it should be an alternative. Something else. In its otherness, it should create conditions for the future and not keep pupils’ experiential horizons in the present. The school should not provide self-affirmation for what the students are, but help them become what they can be.

The future is uncertain. And that is precisely why it is so important for the school to relate to the future and not the present. Therefore, the school should also be something different and not a mirror of society. Through its otherness, the school can provide preparedness for a new life and a new world. When we talk about what the school needs to provide students, this must be at the center.

We often ask what kind of students society needs. I think that question is misplaced. The demand must be a rights-based demand that transcends the students’ own experiential horizons and is future-oriented by focusing on their potential, not their contingent present facticity.

The reform pedagogy nurtured the idea that the distance between school and society would disappear and that identity would prevail. It still perceives itself as progressive (often with the same unreflected starting points regarding identity politics in general in our modern multicultural societies). I see it the opposite way. Hold on to the difference and distance between school and society. Like Adorno once spoke of ‘false intimacy,’ I would like to argue that this is about ‘false identity.’ The school should be its own entity with its own rules and norms. We enter with some of our identities for part of our lives. The school should demand and challenge students. It can make them grow and realize their potential. Going along and building false intimacy and identity rather hinders than helps these future-oriented aspirations.

The reform pedagogy nurtured the idea that the distance between school and society would disappear and that identity would prevail. It still perceives itself as progressive (often with the same unreflected starting points regarding identity politics in general in our modern multicultural societies). I see it the opposite way. Hold on to the difference and distance between school and society. Like Adorno once spoke of ‘false intimacy,’ I would like to argue that this is about ‘false identity.’ The school should be its own entity with its own rules and norms. We enter with some of our identities for part of our lives. The school should demand and challenge students. It can make them grow and realize their potential. Going along and building false intimacy and identity rather hinders than helps these future-oriented aspirations.

To learn, one must be able to “take in” differences. This also requires a demand for distancing. Students are not helped by the school merely reflecting and affirming their own life-world. It should broaden and deepen it. Here, theoretical knowledge becomes important as well. Without it, deepening and perspective on one’s own life-world cannot take place. An identity between school and society would cement students in the present instead of preparing for an unknown and uncertain future.

The school should be the fixed point in young people’s lives where they can come and, like teachers, temporarily withdraw from the storms of family and social life. The school should be an island in a world full of intense changes. To be able to learn things, concentration and opportunities for screening are required. In our hyper-mediatized world, perhaps the latter is particularly important. In the constant digital noise that young people surround themselves with around the clock, islands of distance, calmness, and opportunities for reflection, screening of noise, and processing of information into knowledge are needed. Not to permanently withdraw from the troubles and problems of life-world, but to better cope with the constant real transformations that characterize our lives with the strength, skills, and perspectives that a knowledge and citizenship-based school can provide.

Division of labor is a prerequisite for civilization. This also applies to the school in relation to society. The school cannot and should not solve or accommodate all the problems that a constantly changing open world creates. The school cannot compensate for all the risks of the modernization process. Family and parents – as well as society as a whole – have a responsibility that cannot simply be assumed by the school to replace or compensate for. Many social researchers describe family, norms, and social life as being in dissolution everywhere today. That is precisely why it is so important that the school should not primarily function as a compensatory social institution. Then it loses its soul. Then it loses its aura and ability to function as an energizing dream that everything can be different and that the school can contribute to making it different.

We all have several different identities. We all have different aspirations, backgrounds, and dreams. But in school, we should meet as equals. Different, but equal. When we enter through the school gate, we are all equal. Entering school also means that you (temporarily) leave family and society and enter a limited space with its own rules and goals. For part of the day, we enter a world where we collectively create ourselves as citizens and knowledge practitioners.

If you are to learn something new in school, it must be something other than an extension of pupils’ everyday lives. For the school to be able to catalyze and change, it must be something else and not identical to its surroundings. In today’s society, the school must function as something different, an alternative to the eroding market forces that threaten society by reducing citizens to consumers. Knowledge is a necessary condition for being able to resist this development. When the family or society does not stand up, the school must be able to stand up and take care of the genuine emancipatory interests of the growing generation.

A good school — not least in our meritocratic knowledge society — is an important prerequisite for young people to be able to realize their dreams of improving their conditions in the future. It should help students get out of the self-centered identity fixation they are developmentally in. Today’s over-reliance on the school starting from students’ individual, highly private, and subjective lifeworlds does not work very well. Today, this individualization over-reliance creates more problems than it solves.

The school should educate knowledgeable citizens. A school with religious, ethnic, or profit-making motives is not a good school. The school should meet pupils based on what they can become, not based on what they are. The school should provide pupils with a compass in the landscape of the future so that they can learn to navigate in uncertain waters. To fulfill the principle of hope, the school must be an island of good otherness — unrestricted by all kinds of identity politics. The more the school is drawn into the cumulative dynamics of society, the more it loses its necessary status and self-logic.

If the school is to be a realization of each pupil’s potential rather than a time-bound and contingent facticity, it must be able to build bridges to the pupil’s lifeworld while maintaining the distance between school and society.