Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) has been in the news again, and for good reasons. I actually had a post with the same title back in February of 2012, hence the again in the title. But now, with the irruption of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in the political scene ,and with the discussion of a Green New Deal (discussed here 7 years ago) and the feasibility of higher taxes (here, also long ago, among the many on the topic) taking the center of the political debate, MMT has become trendy. The rise of democratic socialist ideas, since Bernie's 2016 campaign, has brought the fiscal feasibility or responsibility, in the more conservative terminology, of such progressive plans into the center of economic policy debates. Also, the fact that Stephanie Kelton a prominent MMTer is an advisor to Bernie,

Topics:

Matias Vernengo considers the following as important: bernie sanders, Galbraith, Hannsgen, Henwood, Kelton, Krugman, MMT, Ocasio-Cortez, Summers, Wray

This could be interesting, too:

Matias Vernengo writes Serrano, Summa and Marins on Inflation, and Monetary Policy

Matias Vernengo writes The second coming of Trumponomics

Matias Vernengo writes Paul Davidson (1930-2024) and Post Keynesian Economics

Matias Vernengo writes The Economist and the American Economy

I have discussed Modern Monetary Theory in this blog for years (going back to April 2011, when I first found use of the term, to the most recent earlier this year after Olivier Blanchard American Economic Association presidential address last January), and have known the main MMTers going back to at least the mid-1990s, when I was at the New School and working as research assistant to Wynne Godley at the Levy Institute. I guess, I can be seen, to use the term employed by Doug Henwood in his recent Jacobin piece, as a fellow traveller (like Jamie Galbraith), even though I've been critical of some aspects, in particular when applied to developing countries (more on both Henwood and MMT issues in developing countries below).

There are many critiques, which deal with both theoretical issues, mostly concerned with the Functional Finance aspects of MMT, and with the policy and political effects of MMT advising to the left of center Democratic presidential candidates. Note that I will not try to define MMT precisely, since it is a hybrid of economic theories and policy proposals. I would assume that at core it is composed by the ideas of Chartalist and Endogenous Monetary views, Functional Finance, and an Employer of Last Resort (ELR) program as suggested by Greg Hannsgen in his recent presentation at the Eastern Economic Association (EEA), in sessions we co-organized (with the presence of Randy Wray presenting Stephanie Kelton's slides and Josh Mason; Stephanie was with Bernie at the rally in Brooklyn).

My comments will be, for the most part, directed at issues that fall within the Functional Finance part of MMT, and mostly about developed economies like the US (although, I'll have something to say about developing countries like Argentina or Brazil). I might add that Randy suggested that Functional Finance was a late addition to MMT, since this ideas were not known by MMTers in the mid-1990s or so. I think that the original source for the Functional Finance story was Ed Nell, who organized a conference at the New School back in 1997, I think, with Bob Eisner, and many other Old Keynesians. I had read Abba Lerner and Evsey Domar foundational papers in Ed's classes, and I think his influence on MMTers in this area is reasonable to assume.

Let me start with Paul Krugman's critiques of MMT, which have been clear and perhaps the most widely read (but there are many, including critiques by Tom Palley and Sergio Cesaratto here in the blog). So Krugman, in one of his most recent posts, starts by showing that there are many levels of the fiscal deficits that are compatible with full employment (not sure who thinks that this is wrong; I would add the same is true about the rate of interest, and that there is no natural or neutral rate of interest, a point that Keynes made back in the 1930s, and that is coherent with the capital debates, and, hopefully, it will be clear why this is relevant below). Then he argues more problematically, in my view, that crowding out is a serious concern, in his words: "The question then becomes one of tradeoffs: would the things the government could buy with a higher deficit be worth the lost private investment due to a higher interest rate?" But he knows well that the crowding out effect is empirically (if not theoretically) irrelevant, since investment is not particularly responsive to interest rates (he knows it's all about the accelerator); then he moves to the issue of the natural rate itself.

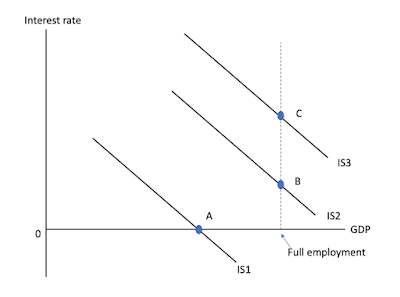

He seems to think two things (he can certainly correct me if I'm wrong). One, that MMT requires that you use monetary policy in order to achieve full employment. Two, that if you are in a situation of like the zero-lower bound, then the central bank cannot bring you back to full employment. That is, her assume that, using his own graph, the economy would be in position A.

So it's unclear what the fuss is all about. If it is because the Fed could, in the MMT story (not sure Functional Finance authors would say that), print money to finance the deficits and bring the economy back to full employment, then the concern might be that it would be inflationary, in a Monetarist sense that printing money might be the cause of inflation. But that does not seem to be his preoccupation (I dealt with the issue of monetization of debt back in May 2011 in a reply to Krugman, who was back then, not surprisingly, criticizing MMT). His concern seems to be that the rate of interest would not go up. But of course, there could be a flat interest rate close to zero, a horizontal monetary policy (MP) line, and the expansion of the IS could be achieved bringing the economy to full employment (right below the C and B points with a zero interest rate).

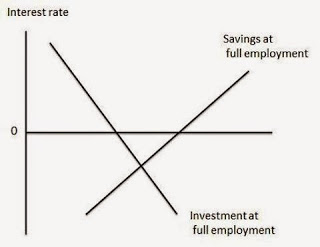

But that doesn't seem to be the issue either. My guess is that he thinks that the problems is more like the one below, from an older post by him, in which the natural rate of interest is negative (my discussion of that here), and the Fed cannot lead the economy to full employment.

So his point is that the Fed cannot make it because it cannot bring the economy to the natural rate of interest, the one that is compatible with full employment and stable prices. He then goes on to criticize Stephanie on her critique of the natural rate, and tells us that: "So what purpose does claiming that the natural rate is a meaningless concept serve? It looks to me like sophistry – word games intended to confuse what should be a simple issue."

I'm not sure what Stephanie said about the natural rate, but I think it is well-established that the natural rate concept is problematic (note that on this some MMTers have said things I would disagree; e.g. Forstater and Mosler suggest here that the natural rate of interest is zero; my discussion of that here). So I think the position that Krugman attributes to her is correct. Paul Samuelson would agree, as he did when he admitted that the capital debates had shown that neoclassical parables cannot hold (on the capital debates read this old post). So let me explain it briefly. There is no sophistry, just pure logic.

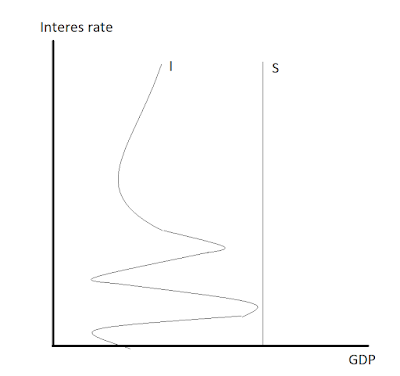

The capital debates show that with factor price reversals, when one good can be said to be capital-intensive at one level of the wage-profit ratio, and labor intensive at another level of the same ratio, there is no monotonic inverse relation between investment and the rate of interest. The investment schedule could look like the one below (my graph), with portions that have a negative slope and some in reverse, and if savings (determined by the level of income as in Keynes' principle of effective demand, rather than a Ramsey inter-temporal model) is given as in the graph below, then there might be no natural rate of interest. Keynes was explicit about that in the General Theory. That means that the monetary authority can set the rate of interest, what Keynes referred to as the normal rate, that was conventional, and that fiscal policy can be used to bring the economy to full employment. Btw, I think that overall Krugman and Kelton agree on that. Krugman says he's defending the theory, not the policy proposals, since he thinks they agree on that.

I'll comment briefly on two additional critiques of MMT, the one by Larry Summers, the ex-Treasury Secretary and advisor to the Clintons and Obama, and the one by Doug Henwood, an influential Marxist (see my discussion of his comments, and others, on Marx for the New York Times here), and writer of a very good book on Wall Street. I am sorry to say that both have too many arguments of authority and ad hominem attacks on some MMT authors, which I'm not interested in discussing. But there are a few substantive issues. One is the danger of inflation (that I'm glad Krugman seemed less keen on) and the others are on MMT and developing countries, and the political relevance and practicality of MMT proposals (here most critics have in mind the Bernie/Ocasio agenda of Medicare for all, cheap or free college tuition in public institutions, a jobs guarantee, and a Green New Deal).

I'll start with Henwood. His major issue is inflation, I would say. He says: "That brings us to the next problem: inflation. When the printing presses run freely, it’s not only reactionaries who think that runs the risk of spiraling prices. As I was researching this piece, many people to whom I described MMT, from Democrats to Marxists, brought it up as a worry. MMTers are coy about the topic — they never say how much is too much, and they profess great confidence in their ability to control it." Let me start by saying that inflation has not been a problem in 40 years, while wage stagnation is a central one. But if one is concerned about it, at least one should get the correct analytical tools to discuss it.

He tells us that: "The standard view of the Weimer inflation is that the German economy, severely damaged by World War I and forced to make huge reparations payments to the victors, wasn’t up to the task — it just didn’t have the productive capacity, and its citizens were both unwilling and unable to pay the necessary taxes. So instead the government just printed money and spent it, not only to pay its own bills, but to support bank lending to the private sector." First, that's NOT the standard view of the hyperinflation in Germany. You can read here the standard story, and I cite even a conservative historian like Niall Ferguson admitting that the monetarist story embraced by Henwood is NOT the dominant view among historians. The notion that the economy was at full capacity (didn't have productive capacity) and that printing money caused inflation is what Cagan thought about it. A more refined and somewhat structural story is the dominant view actually. In my view, it is clear that debt in foreign currency (not domestic), and, hence, the external problems of the current account, that forced depreciation, together with wage resistance are at the core of the hyper., German and many others.