There are many myths about the Phillips Curve and the so-called Monetarist Counter-Revolution of the 1960s and 1970s. Forder's book is a good read on some of these issues. Jeremy Rudd's recent paper is also a must read, and has now been accepted for publication in the Review of Keynesian Economics (ROKE).It debunks the myth about the importance of inflationary expectations for explaining the Great Inflation of the 1970s, and casts doubts about the Monetarist Counter Revolution, the Rational Expectations one, and that would include the more recent New Keynesian developments that include a lot from both. Rudd's paper suggests that there is a simpler explanation for the acceleration of inflation back then, and the Great Moderation since the 1990s. In his words:"Another way of stating this

Topics:

Matias Vernengo considers the following as important: Forder, Phillips Curve, Review of Keynesian Economics, ROKE, Rudd

This could be interesting, too:

Matias Vernengo writes Paul Davidson (1930-2024) and Post Keynesian Economics

Robert Waldmann writes What are we To Do With the Phillips Curve ?

Matias Vernengo writes Paul Davidson (1930-2024)

NewDealdemocrat writes Immigration and the housing market freeze are making the “last mile” of disinflation harder, not the Phillips Curve

There are many myths about the Phillips Curve and the so-called Monetarist Counter-Revolution of the 1960s and 1970s. Forder's book is a good read on some of these issues. Jeremy Rudd's recent paper is also a must read, and has now been accepted for publication in the Review of Keynesian Economics (ROKE).

It debunks the myth about the importance of inflationary expectations for explaining the Great Inflation of the 1970s, and casts doubts about the Monetarist Counter Revolution, the Rational Expectations one, and that would include the more recent New Keynesian developments that include a lot from both. Rudd's paper suggests that there is a simpler explanation for the acceleration of inflation back then, and the Great Moderation since the 1990s. In his words:

"Another way of stating this point is that an important feature of inflation dynamics after the mid- 1990s appears to be the lack of a strong wage–price spiral (or of any significant year-to-year feedback between wage growth and inflation)... An observation about the actual nature of the 'wage bargaining process' is helpful at this point."

Old Keynesian stories about cost-push versus demand-pull inflation come back to mind. He suggests essentially that worker's wage bargaining power has been weakened, and that reflects in less impact of labor costs on actual inflation. Again, in his words:

"We can make a reasonable case that reactions of labor costs to actual inflation were an important feature of the inflation process in the 1970s. In particular, without this channel’s being present, it is nearly impossible to explain why movements in food prices left a durable imprint on core inflation—unlike energy, which can plausibly be viewed as a broader input to industry, changes in agricultural prices shouldn’t act like a cost shock to firms outside the food sector."

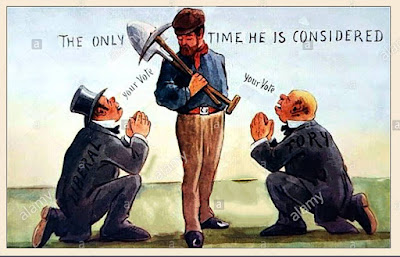

This suggests a preoccupation of the profession with more concrete, objective causes of inflation dynamics, and that bargaining power of the labor class matters. Martin Sandbu has suggested a few months ago in his Financial Times column that:

"To be precise, we may be witnessing the manifestation of two outmoded ideas: that the relative power of economic classes alters macroeconomic outcomes; and that macroeconomic policy tilts that relative power."

Sandbu also noted that in this recession it is Michal Kalecki, not Keynes, the old and forgotten master that we should bring back from the dead. While I do think that Kalecki should always be remembered and was and continues to be relevant, it is less clear that the wage bargaining position of the working class will recover anytime soon. Sure, if Dems manage to pass the more robust social spending bill, with the extra US$ 3.5 trillion, things would look a bite better. Hope springs eternal.