In my previous post, I laid out some issues with the methodology being used to explore the relationship between inflation and asset prices. One issue that I raised was with respect to the observation that inflation below 1% seemed to lead to lower stock market earnings. In the previous post I pointed out that this was likely misleading: it was unlikely that the low price growth itself was giving rise to such poor earnings; it was far more likely that this was mainly being driven by recessions that in turn caused low price growth. In this short post, I hope to be able to show this. Here we will be using a different sample due to our needing quarterly real GDP figures to do the calculations. Here is the full sample of real earnings growth categorised by inflation bucket.

Topics:

Philip Pilkington considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

In my previous post, I laid out some issues with the methodology being used to explore the relationship between inflation and asset prices.

One issue that I raised was with respect to the observation that inflation below 1% seemed to lead to lower stock market earnings. In the previous post I pointed out that this was likely misleading: it was unlikely that the low price growth itself was giving rise to such poor earnings; it was far more likely that this was mainly being driven by recessions that in turn caused low price growth.

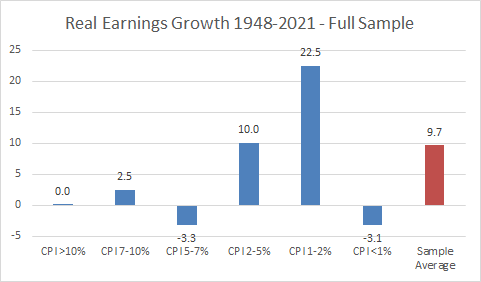

In this short post, I hope to be able to show this. Here we will be using a different sample due to our needing quarterly real GDP figures to do the calculations. Here is the full sample of real earnings growth categorised by inflation bucket.

Here we see much the same pattern we saw in the post-1925 sample. It shows that historically high inflation (above 5%) and low inflation (below 1%) have been associated with low real earnings growth. Now let’s strip out recessions. (For the sake of simplicity I will not use NBER recessions but rather any quarter that saw negative real GDP annual growth numbers).

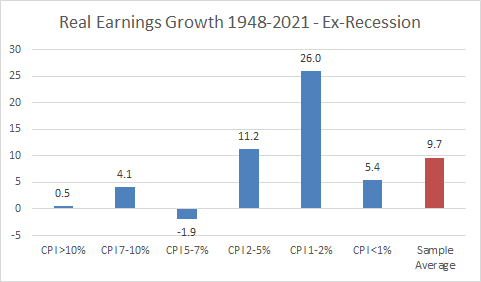

As predicted, the negative real earnings growth in very low inflation regimes disappears. True, the real earnings growth in these low inflation regimes is lacklustre, but it is not negative.

In addition to this, real earnings growth in high inflation regimes has also improved on a relative basis. This means that at least some of the impact that see on real earnings during inflations is actually due to the recessions that take place in those inflations.

This is a fairly easy exercise. It was fairly obvious when given any thought whatsoever that the poor earnings growth in very low inflation regimes was probably driven by recessions. The really interest question is this: is there a variable that is not inflation that might be driving the low returns in the inflationary period we have in the sample?