Many today are examining the impact that inflation has on asset prices. One of the best papers on the topic is by Harvey et al and it is well worth a look. What I am going to write here does not refute these sorts of analyses, but I think it raises issues that at least serve to lower our confidence in the findings. The issues that I want to explore are as much methodological as they are empirical, but these two aspects can be approached simultaneously. When analysing equity returns, the tendency is to examine what has happened in the past and extrapolate this into the future. There is nothing inherently wrong with this approach and it certainly gives us one window into the dynamics of asset markets, but sometimes it can prove misleading. This especially so when it comes to a

Topics:

Philip Pilkington considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

Many today are examining the impact that inflation has on asset prices. One of the best papers on the topic is by Harvey et al and it is well worth a look. What I am going to write here does not refute these sorts of analyses, but I think it raises issues that at least serve to lower our confidence in the findings.

The issues that I want to explore are as much methodological as they are empirical, but these two aspects can be approached simultaneously.

When analysing equity returns, the tendency is to examine what has happened in the past and extrapolate this into the future. There is nothing inherently wrong with this approach and it certainly gives us one window into the dynamics of asset markets, but sometimes it can prove misleading. This especially so when it comes to a very historically contigent phenomenon like inflation.

Take the well-known correlation between energy stock returns and CPI. Analysts often take this correlation to mean that energy stocks are an inflation hedge. In assuming this they are implicitly saying something like: “Inflation is a cause of relative energy stock outperformance.” As evidence of this, they show the correlation between these two phenomena in the historical data.

But now consider this: that series is dominated by a single inflation, the inflation of the 1970s. Yet this inflation itself was in large part caused by a run-up in energy prices as the OPEC countries hiked the oil price in response to the Yom-Kippur war in 1973. The more realistic causal account then runs something like this: OPEC raised oil prices for geopolitical reasons; this gave a boost to energy stocks; it also gave rise to inflation.

The correlation between inflation and energy stocks is thus spurious. It is driven by a third variable: the OPEC price hike. All this correlation tells us is that energy stocks will do well when energy prices are hiked. Not exactly a genius-level insight.

To get a better sense of the causal dynamics we should step back. In theory, how should inflation impact stocks? Presumeably it should impact them through its effects on real earnings. If inflation hits and real earnings remain buoyant then – not to put too fine a point on it – who cares? If stock prices fall during an inflation and earnings remain buoyant investors should see that as a buying opportunity and so inflations are merely a behavioural driver of bargain basement buying periods for smart investors. So, in order for inflation to have a true negative impact on equities it should be hitting the company’s bottom-line – otherwise it is just noise.

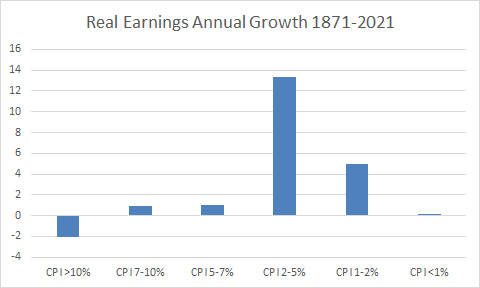

Here is real earnings annual growth for the S&P sorted into various inflation buckets using Shiller’s data.

Now we are starting to get a sense of how inflation actually impacts companies’ bottom lines. It appears that, at least historically, high and very low inflation regimes have overlapped with periods of low real earnings growth.

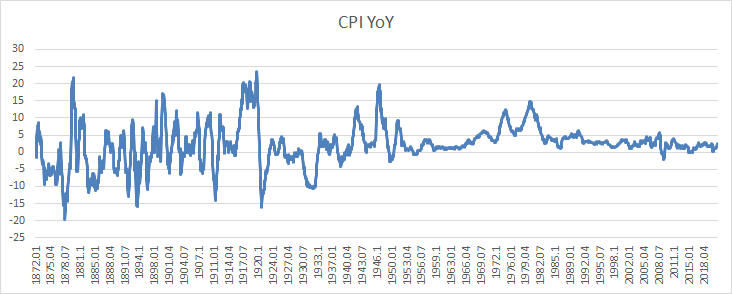

Let us pause here for a moment to firm this up because in this data there are two very different inflationary regimes as can be seen below.

Up until around 1925 CPI was incredibly unstable. This was the period of flex-prices in the US. After this, prices became much stickier. So, let’s also seperate out the more sticky price regime we live in today to make sure we’re not being fooled by structural breaks in the data.

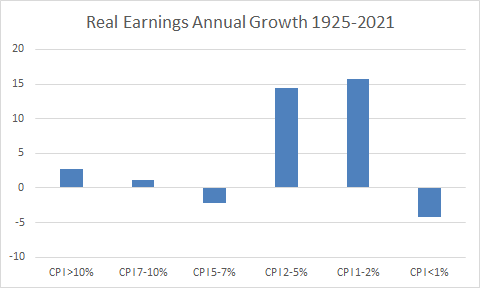

The post-1925 era is a little different to the full sample. Very low inflation/deflation is now the worst possible regime for real earnings growth historically. CPI of 1-2% is now the sweet spot, but the full sample sweet spot of 2-5% is still pretty rosy.

At this point it would be tempting to tell a tidy story about inflation and real earnings growth. But remember that spurious correlation from earlier? Let’s tread carefully.

One simple test to see whether the various levels of inflation are causing the low real earnings growth is to run non-linear regressions. If the inflation is causing the low real earnings growth we should see that relationship clearly in a regression. Since the historical data suggests that high inflation (over 5%) and low inflation (under 1%) overlaps with low real earnings growth, we should be able to fit a second-order polynomial to the data and it should look like an upside-down smile. Crucially, however, this second-order polynomial should produce a high correlation coefficient. Here is the model fitted to the data – both full sample and post-1925.

The shape of the fitted curve looks good but the correlation, well, it sucks.

This implies – implies, not proves – that there is no hard and fast relationship between inflation and real earnings growth. Thus all the historical data tells us is that, in the data sample that we have, real earnings growth were lower in both low and high inflation periods. But it seems likely that something else could have been causing the low real earnings growth.

Take the example of low inflation growth for simplicity. Why would periods of low real earnings growth overlap with periods of low inflation – especially in the fixed-price regime post-1925? A little thinking and the answer becomes obvious: these are recessionary or depressionary periods. It is not the disinflation causing the low real earnings growth, it is probably the recession/depression.

Okay, so what should we learn from all this? Others will tell you what to invest in based on previous events. I will tell you to take these analsyses with a large pinch of salt. In reality, because inflation is such an historical and contingent phenomenon, at best we will need a much, much more sophisticated analysis to determine the actual effects of inflation on equities and on equities market. We will need to control for other factors, most notably fluctuations in GDP and we would probably do better focusing on the point at which inflation may impact the bottom-line of companies – not on simple correlations with asset returns.

A negative finding, yes. But a necessary one to stomach before moving forward if we are to approach this seriously.