This article first appeared in the Indian journal Economic and Political Weekly on 13 November, 2021. Fermi Paradox In a recent article, Yıldızoğlu (2021) reminded us of the Fermi Paradox, which can be summarised as: Although the probability of the existence of other forms of life in the universe is sufficiently high, why have we not met any? Enrico Fermi, the Italian–American physicist and the creator of the world’s first nuclear reactor, was probably not the first person who asked: “but where is everybody?” However, the paradox he formulated led astronomers, astrophysicists, planetary scientists, and others to offer more than a dozen explanations. One of these explanations is reminiscent of our civilisation: Intelligent life self-destructs. Through weapons of mass destruction, planetary

Topics:

Ahmet Öncü & T.Sabri Öncü considers the following as important: Article, Ecological crisis, Financial Architecture, International & World, Long Read, private debt, public debt

This could be interesting, too:

Jeremy Smith writes UK workers’ pay over 6 years – just about keeping up with inflation (but one sector does much better…)

T. Sabri Öncü writes Argentina’s Economic Shock Therapy: Assessing the Impact of Milei’s Austerity Policies and the Road Ahead

T. Sabri Öncü writes The Poverty of Neo-liberal Economics: Lessons from Türkiye’s ‘Unorthodox’ Central Banking Experiment

Ann Pettifor writes Global Economic Governance: What’s “Growth” Got to Do with It?

This article first appeared in the Indian journal Economic and Political Weekly on 13 November, 2021.

Fermi Paradox

In a recent article, Yıldızoğlu (2021) reminded us of the Fermi Paradox, which can be summarised as: Although the probability of the existence of other forms of life in the universe is sufficiently high, why have we not met any?

Enrico Fermi, the Italian–American physicist and the creator of the world’s first nuclear reactor, was probably not the first person who asked: “but where is everybody?” However, the paradox he formulated led astronomers, astrophysicists, planetary scientists, and others to offer more than a dozen explanations.

One of these explanations is reminiscent of our civilisation: Intelligent life self-destructs. Through weapons of mass destruction, planetary pollution, or manufactured lethal diseases, intelligent species commit suicide and become extinct. And, to these, we add economic and social collapses under extreme debt burden as another cause for self-destruction.[1]

Climate Crisis

“Climate change is the defining crisis of our time and it is happening even more quickly than we feared,” states the United Nations (UN),[2] and adds:

No corner of the globe is immune from the devastating consequences of climate change. Rising temperatures are fuelling environmental degradation, natural disasters, weather extremes, food and water insecurity, economic disruption, conflict, and terrorism. Sea levels are rising, the Arctic is melting, coral reefs are dying, oceans are acidifying, and forests are burning.

The world recognized climate change as a problem for the first time at the 1979 World Climate Conference, now referred to as the First World Climate Conference (FWCC), held in Geneva. The declaration the FWCC issued called the governments to foresee and prevent potential human-made changes in climate that might be adverse to the well-being of humanity. Further, the FWCC endorsed the establishment of a World Climate Programme under the joint responsibility of the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), and the International Council of Scientific Unions (ICSU).[3]

After many intergovernmental conferences in the succeeding decade, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), established in 1988 by the UNEP and WMO, released its first assessment report in 1990. This report confirmed the scientific evidence for climate change and provided the basis for negotiations on the climate change convention. Then, sponsored by the WMO, UNEP and other international organisations, came the 1990 Second World Climate Conference (SWCC), which featured negotiations and ministerial-level discussions among 137 states and the European Community. Although the final declaration of the SWCC, adopted after hard bargaining, did not specify any international targets for reducing emissions, it supported several principles later included in the Climate Change Convention.[4]

After the December 1990 UN General Assembly approval of the treaty negotiations, the 150 countries strong Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee for a Framework Convention on Climate Change (INC/FCCC) had drafted the Convention, adopted in New York in May 1992. Shortly after, in June 1992, at the Rio de Janeiro Earth Summit, 154 states and the European Community signed the FCCC and the Convention entered into full force on 21 March 1994. From March 1994 until its dissolution in February 1995, the INC had done the preliminary work, and the Conference of the Parties (COP) became the ultimate authority of the Convention.[5] Since the first Conference of the Parties, now called COP01, in Berlin, 28 March-7 April 1995, there had been 25 such conferences. The 26th, COP26, is still going on as we write this article.

In closing this section, we mention that the most notable COPs before COP26 were COP03 in Kyoto, 1-10 December 1997, COP15 in Copenhagen, 7-18 December 2009, and COP21 in Paris, 30 November-12 December 2015. These three conferences were the ones where the parties made commitments to reduce emissions, financial and otherwise. What is sad is that despite all the promises in these conferences, almost nothing significant has gotten accomplished so far. And a majority of the observers do not expect much from the ongoing COP26, either. Indeed, Project Syndicate even called COP26 “the great COP out.” [6]

Global Debt

Since we have written about the global debt overhang extensively in our earlier articles, such as Öncü (2016, 2017, 2019) and Öncü and Öncü (2020a, 2020b), we fast forward to the 14 September 2021 Global Debt Monitor of the International Institute of Finance (IIF). We note that the IIF database currently covers 61 countries ̶ 29 Mature Market (developed) and 32 Emerging Market (high-income developing). Since the IIF database does not cover middle-income and low-income developing countries at all, the below global statistics are global in the sense of these 61 countries only.

As the IIF (2021) reports, global debt reached a fresh all-time high of $296 trillion in the second quarter of 2021, that is, Q2 2021, increasing by about $36 trillion since the Covid-19 pandemic economic sudden stop that hit the world in Q1 2020. And these figures do not include middle-income and low-income developing countries, so the actual global debt must be way above $296 trillion. Only the annual interest payments on this debt would exceed the estimated $4 trillion to $5 trillion per year climate investments to achieve net zero emissions by the mid-century the parties agreed at the 2015 COP21 in Paris, by far.[7][8] No wonder the IIF (2019) warned on 14 November 2019 that high debt burdens could curb efforts to tackle climate risk. The global debt was only $250 trillion then, in Q2 2019.

Figure 1: Global Sectoral Indebtedness

Source: IIF Global Debt Monitor

Figure 1 shows how global sectoral indebtedness changed from Q4 2019 to Q2 2021. It is evident from the figure that, despite the dominant free-market ideology that requires austerity, the pandemic-triggered economic sudden stop in Q1 2020 forced the governments to borrow and spend to stimulate the economy, as their debt stock increased by about 21% from Q4 2019 to Q2 2021. Compare this 21% increase with about 12% increase in the households and non-financial corporates indebtedness and about 9% increase in the financial sector indebtedness. But we should not conclude from these aggregate figures that this ability to borrow and spend to stimulate the economy has been an evenly distributed ability across all governments. As the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), Trade and Development Report (TDR) 2021 documents, with few exceptions, the developing countries have not enjoyed the policy independence enjoyed by the developed economies and economies issuing global currencies (UNCTAD 2021).

However, the global debt-to-GDP (Gross Domestic Product or Income) ratio fell by nine percentage points from its peak of 362% in Q1 2021 to 353% in Q2 2021, apparently because of global recovery in Q2 2021. Despite this drop, the improvement has been uneven across countries, as the IIF (2021) reports. Further, the recovery has not been strong enough to bring debt ratios below pre-pandemic levels except for five of the 61 countries in their database, according to the IIF. Given the analysis in UNCTAD (2021), these observations of the IIF are not surprising.

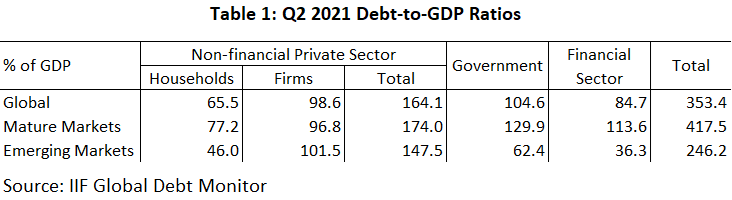

To elaborate upon this, we summarise the Q2 2021 sectoral debt-to-GDP percentages for the IIF database countries in Table 1. Before discussing Table 1, we should mention that inclusion of China, the second-largest economy in the world, in the Emerging Markets (high-income developing countries) rather than Mature Markets (developed countries) category distorts the statistics. With this in mind, let us now look at Table 1.

It is evident from the table that even the high-income developing countries are not capable of escaping austerity imposed on all developing countries by the developed countries. While the high-income developing countries government debt-to GDP ratio in Q2 2021 is only 62.4%, it is 129.9% for the developed countries. Apparently, the developed country governments are not subject to the strict austerity requirements the developing country governments are subject to, for otherwise, such a discrepancy could not have existed.

Looking at the financial sector, we see that the financial sector in developed countries is more indebted (113.6% of the GDP) than in high-income developing countries (36.3% of the GDP). This difference is natural. Banks dominate the financial sector in the latter countries, and banks do not borrow much for the credit they extend and other assets they buy. They fund these assets mainly by creating deposits, liabilities not classified as debt.

However, irrespective of the distortion by China, it is the non-financial private sector that is still more indebted than other sectors in both developed and high-income developing countries. The difference is that while the non-financial firms sector is almost equally indebted in both, the household sector in developed countries is substantially more indebted than the household sector in the high-income developing countries. Furthermore, as the UNCTAD TDR 2021 documents, while in developed and high-income developing countries, the non-financial private sector is more over-indebted, in middle-income and low-income developing countries, the public sector is more over-indebted (UNCTAD 2021). That is, the high debt burdens that could curb efforts to tackle climate risk the IIF (2019) warned are neither only private nor only public, but both.

To sum up, although the public debt in developed countries has increased substantially after the pandemic, the over-indebtedness of the non-financial private sector in both developed and high-income developing countries is still their main issue. At 164% of the GDP, this non-financial private sector debt is unsustainably high by any historical standard. Many of these debts will become unserviceable or unpayable if the already shaky global economy deteriorates, forcing governments in developed and high-income developing countries to rescue. And their already high debt burden will get even higher. Combine this with the already high government debt burden in middle-income and low-income developing countries. These will severely constrain governments’ ability to spend on climate change-related projects for many years to come, and our hopes to make the necessary investments and innovations to address the now existential climate crisis on time will diminish (Öncü 2020). Do we not need a Global Debt Jubilee? Yes, but for the Fermi Paradox?

COP26 and GFANZ

The Glasgow Finance Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ) was launched in April and chaired by the UN Special Envoy on Climate Action and Finance, Mark Carney, a former governor of the Bank of England and the Finance Adviser of the United Kingdom Prime Minister for COP26. Now consisting of more than 450 banks, insurers and investment managers from 45 countries, the GFANZ defines itself as a global coalition of leading financial institutions committed to accelerating the decarbonisation of the economy.[9] It includes such familiar names as BlackRock, Vanguard, State Street, Bank of America, HSBC, Goldman Sachs, and the like. The total assets of the GFANG members is about $130 trillion, with $63 trillion coming from banks, $57 trillion from investment managers and $10 trillion from asset owners such as pension funds (Walker and Hodgson 2021).

In the 11 October 2021 press release of their Call to Action from the Group of 20 (G20) countries for greater and faster climate action, the GFANZ wrote:[10]

GFANZ’s Call to Action recognises the critical role financial services firms must play to support the transition to a green economy, which requires annual clean energy investment to more than triple by 2030 to around $4 trillion. However, if the world is to achieve an orderly transition to Net Zero – and so avoid the massive human, social, economic loss and financial instability associated with failing to meet the objectives of the Paris Agreement – more governments must follow through on the commitments of the Paris Agreement and ensure a Just Transition to a net zero global economy.

Although Carney (2021), now joined by Michael Bloomberg as the co-chair, wrote in his Financial Times article on 29 October 2021 that $100 trillion was “the minimum amount of external finance needed for the sustainable energy drive over the next three decades if it is to be effective,” he did not make any commitment in the name of the GFANZ. Similarly, what Walker and Hodgson (2021) wrote in the Financial Times was:

The Mark Carney-led coalition of international financial companies signed up to tackle climate change has up to $130tn of private capital committed to hitting net zero emissions targets by 2050.

Apart from the fact that this $130 trillion is not the capital but the total assets of the GFANZ, it is not clear from this statement that the GFANZ actually committed this amount, either.

Nevertheless, the public interpretation of the above was that the GFANZ committed $130 trillion of capital for net-zero by 2050. Luckily, the Lex team of the Financial Times intervened and clarified that $130 trillion is not ready funds but the total assets managed by member financial institutions of the GFANZ.[11] The Lex team also wrote:

The reality is that carbon transition will require huge state intervention and investment.

So we still do not know who will fund that $4 trillion to $5 trillion annual climate investments over the next 30 years and how as we write this article. And it looks unlikely that we will learn who and how any time soon.

Covid-19 and SDRs

In the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic, many had called upon the IMF to allocate about $1 trillion worth Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) to help developing countries address the Covid-19 crisis and its economic outcomes. On 12 April 2020, even the Financial Times editorial board argued that despite that only 47% would go to developing countries, the IMF should make a one trillion SDR (about $1.3 trillion) allocation as a matter of moral duty.[12] That the economically strong countries get the lion’s share results from that once agreed, the allocation gets distributed to member countries in proportion to their quota shares at the IMF. And the economically strong countries have larger quota shares.

The main problem with the SDR allocation is that it requires the Board of Governors approval by an 85 per cent majority of the total voting power of the members in the SDR Department of the IMF, and the United States (US) has a 16.5% voting power. Unfortunately, on 15 April 2020, the Trump Administration Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin opposed the allocation, arguing that about 70% of the SDR allocation would go to the G20, most of which did not need additional SDRs to respond to the crisis.[13] That is, Mnuchin blocked the SDR allocation.

But, after the Biden Administration replaced the Trump Administration in January 2021, the US position has changed. With the support of the Biden Administration Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, the Board of Governors of the IMF approved a general allocation of about SDR 456 billion, equivalent to about $650 billion, on 2 August 2021, effective 23 August 2021. Although this allocation is the largest in the history of the IMF, in light of the financing needs we discussed in earlier sections, it is minuscule to address the climate change and over-indebtedness problems the world faces.

Since the IMF creates the SDRs at the stroke of a pen at no cost to anyone, what constrain the size of the allocations are not economic but political reasons. One of the notable political reasons is that countries issuing global reserve currencies perceive the SDR as a threat, fearing that the SDR may rob the global reserve currency status off of theirs. Another notable political reason is that some countries have concerns about low-income countries cashing out the added SDRs to pay off the official bilateral or private foreign debt that could shield the foreign creditors from an expected wave of defaults.[14] We should mention that China is the largest official bilateral lender. Of course, there are other political reasons, but our proposal addresses these two.

Our Proposal to the IMF

According to the IMF,

[t]he SDR is neither a currency nor a claim on the IMF. Rather, it is a potential claim on the freely usable currencies of IMF members. SDRs can be exchanged for these currencies.[15]

When the IMF makes a new SDR allocation to one of its member countries, it makes two entries on its SDR Department’s balance sheet: SDR Allocations to the member country on the assets side and SDR Holdings of the member country on the liabilities side. That is, SDR Allocations are assets, and SDR Holdings are liabilities of the SDR Department. For the member country, the opposite is the case: SDR Holdings are assets, and SDR allocations are liabilities of the member country.

The interest rates the IMF charges on SDR Allocations and pays on SDR Holdings are the same interest rate called SDRi, defined on the SDR Interest Rate Calculation webpage of the IMF.[16] Therefore, as long as the member country SDR Holdings are equal to its SDR Allocations, neither the IMF nor the member country makes any interest payments as they net out.

Also note that if one of the member countries lends some SDR Holdings to another member country at the interest rate SDRi, provided the borrowing member country does not exchange the borrowed SDR Holdings for any of the freely usable currencies of IMF members, neither the IMF nor the lending member country nor the borrowing country makes any interest payments as these interest payments also net out.

It is clear that if the above is what all happens, then the SDR is no threat to any of the global reserve currencies. But, then, what can be the purpose of the SDRs?

To answer this question, let us look at the Statistical Treatment of SDR Allocation: Frequently Asked Questions document of the IMF.[17] As this document explains, domestic arrangements for holding SDRs and the accounting treatment differ across the IMF member countries according to differences in legal and institutional frameworks. In some IMF member countries, the central government performs some or all of the central bank functions. The SDR accounting in such countries is rather complicated. To simplify the matters, we focus only on those member countries, which constitute the majority, where this does not happen.

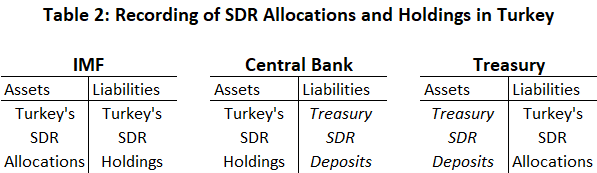

In the majority of these member countries, the central bank records the SDR Holdings and SDR Allocations on its balance sheet as assets and liabilities, respectively. And in the majority of the remaining member countries, a government agency such as the Treasury does the same. However, there are other member countries where neither happens. One such example is the Republic of Turkey. Table 2 shows the Republic of Turkey’s accounting treatment of the SDRs.

In Turkey, while the Central Bank records the SDR Holdings as assets, the Treasury records the SDR Allocations as liabilities on their respective balance sheets. And in return, the Central Bank creates SDR deposits for the Treasury that are liabilities of the Central Bank and assets of the Treasury. The point is that, although the Republic of Turkey has never done this, there are no legally binding constraints on the Treasury that prevent it from moving these SDR deposits to its Turkish lira account at the Central Bank from which it makes its payments. The Central Bank can do this transfer at the prevailing SDR to the Turkish lira exchange rate. Then the Turkish government can do whatever it likes with these deposits, except that it cannot pay official bilateral and private foreign creditors unless it buys hard currencies, which would depreciate the Turkish lira.

What we propose to the IMF is a new SDR allocation with the following conditions:

(i) All IMF member countries agree to record SDR holdings on the central bank and SDR allocations on the treasury balance sheets, respectively. (ii) All IMF member countries agree not to exchange the newly created SDRs for other freely usable currencies of IMF members directly. (iii) All IMF member country central governments agree to convert the SDR deposits their central banks created for them to their domestic currencies to spend on climate investments, domestic debt forgiveness and other collectively decided social projects.

We believe that a new SDR allocation along the above lines or similar would alleviate the political resistance.

To conclude

We do not expect the IMF can create all of the $130 to $150 trillion necessary for climate investments over the next 30 years through $4 trillion to $5 trillion annual SDR allocations. But every bit will help. There is no doubt that carbon transition will require large government intervention and spending, and the IMF can help the governments of the developing countries finance some of this spending as we described above. For, otherwise, the Fermi Paradox holds!

Ahmet Öncü ([email protected]) is a Professor of Sociology at Bahçeşehir University in İstanbul, Turkey. T. Sabri Öncü ([email protected]) is an independent economist also in İstanbul, Turkey.

References

Carney, Mark (2021): “Mark Carney: the world of finance will be judged on the $100tn climate challenge,” The Financial Times, 29 October.

https://www.ft.com/content/d9e4ebb9-f212-406a-90d5-73b4276539e6

IIF (2019): “High debt may exacerbate climate risk,” Global Debt Monitor, 14 November.

IIF (2021): “Reassessing the Pandemic Impact,” Global Debt Monitor, 14 September.

Öncü, T Sabri (2016): “It’s the Private Debt, Stupid!” Economic & Political Weekly, Vol 51, No 46, pp 10-11.

Öncü, T Sabri (2017): “Bad Bank Proposal for India: A Partial Jubilee Financed by Zero Coupon Perpetual Bonds,” Economic & Political Weekly, Vol 52, No 10, pp 12–15.

Öncü, T Sabri (2019): “Non-financial Private Debt Overhang,” Economic & Political Weekly, Vol 54, No 45, pp 10-11.

Öncü, T Sabri (2020): “Triggering a Global Financial Crisis: Covid-19 as the Last Straw,” Economic & Political Weekly, Vol 55, No 11, pp 10-12.

Öncü, Ahmet and T. Sabri Öncü (2020a): “Debt, Wealth and Climate: Globally Coordinated Climate Authorities for Financing Green,” Economic & Political Weekly, Vol 55, No 16, pp 20-23.

Öncü, Ahmet and T. Sabri Öncü (2020b): “A Consortium Proposal to the SDR Basket Countries,” Economic & Political Weekly, Vol 55, No 46, pp 10-12.

UNCTAD (2021): “From recovery to resilience: the development dimension,” Trade and Development Report, 28 October.

Walker, Owen and Camilla Hodgson (2021): “Carney-led finance coalition has up to $130tn funding committed to hitting net zero,” The Financial Times, 3 November. https://www.ft.com/content/8f7323c8-3197-4a69-9fcd-1965f3df40a7

Yıldızoğlu, Ergin (2021): “Fermi Paradoks ve İklim Krizi (Fermi Paradox and Climate Crisis),” Cumhuriyet, 28 October.https://www.cumhuriyet.com.tr/yazarlar/ergin-yildizoglu/fermi-paradoks-ve-iklim-krizi-1880193

Footnotes

[1] https://www.space.com/37157-possible-reasons-we-havent-found-aliens.html

[2] https://www.un.org/en/un75/climate-crisis-race-we-can-win

[3] https://unfccc.int/cop3/fccc/climate/fact17.htm

[4] ibid

[5] ibid

[6] https://www.project-syndicate.org/bigpicture/the-great-cop-out

[7] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-renewables-idUKKBN2221P3

[8] https://www.sifma.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Climate-Finance-Markets-and-the-Real-Economy.pdf

[10] https://assets.bbhub.io/company/sites/63/2021/10/GFANZ-press-release-call-to-action.pdf

[11] https://www.ft.com/content/87690ee9-c9b1-44b6-881b-368139560295?shareType=nongift

[12] https://www.ft.com/content/2691bfa2-799e-11ea-af44-daa3def9ae03

[13] home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm982

[14] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-g20-usa-idUSKBN2AP1U0

[15] https://www.imf.org/en/About/Factsheets/Sheets/2016/08/01/14/51/Special-Drawing-Right-SDR

[16] https://www.imf.org/external/np/fin/data/sdr_ir.aspx

[17] https://www.imf.org/external/np/exr/faq/pdf/sdrfaqsta.pdf