From Lars Syll The NAIRU story has always had a very clear policy implication — attempts to promote full employment are doomed to fail since governments and central banks can’t push unemployment below the critical NAIRU threshold without causing harmful runaway inflation. Although a lot of mainstream economists and politicians have a touching faith in the NAIRU fairy tale, it doesn’t hold water when scrutinized. One of the main problems with NAIRU is that it is essentially a timeless long-run equilibrium attractor to which actual unemployment (allegedly) has to adjust. If that equilibrium is itself changing — and in ways that depend on the process of getting to the equilibrium — well, then we can’t really be sure what that equilibrium will be without contextualizing unemployment in

Topics:

Lars Pålsson Syll considers the following as important: Economics, economy, Finance, inflation, Uncategorized, Unemployment

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Schuldenbremse bye bye

Lars Pålsson Syll writes What’s wrong with economics — a primer

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

from Lars Syll

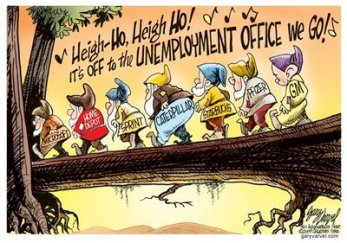

The NAIRU story has always had a very clear policy implication — attempts to promote full employment are doomed to fail since governments and central banks can’t push unemployment below the critical NAIRU threshold without causing harmful runaway inflation.

Although a lot of mainstream economists and politicians have a touching faith in the NAIRU fairy tale, it doesn’t hold water when scrutinized.

Although a lot of mainstream economists and politicians have a touching faith in the NAIRU fairy tale, it doesn’t hold water when scrutinized.

One of the main problems with NAIRU is that it is essentially a timeless long-run equilibrium attractor to which actual unemployment (allegedly) has to adjust. If that equilibrium is itself changing — and in ways that depend on the process of getting to the equilibrium — well, then we can’t really be sure what that equilibrium will be without contextualizing unemployment in real historical time. And when we do, we will see how seriously wrong we go if we omit demand from the analysis. Demand policy has long-run effects and matters also for structural unemployment — and governments and central banks can’t just look the other way and legitimize their passivity re unemployment by referring to NAIRU.

NAIRU does not hold water simply because it does not exist — and to base economic policy on such a weak theoretical and empirical construct is nothing short of writing out a prescription for self-inflicted economic havoc.

NAIRU wisdom holds that a rise in the (real) interest rate will only affect inflation, not structural unemployment. We argue instead that higher interest rates slow down technological progress – directly by depressing demand growth and indirectly by creating additional unemployment and depressing wage growth.

As a result, productivity growth will fall, and the NAIRU must increase. In other words, macroeconomic policy has permanent effects on structural unemployment and growth – the NAIRU as a constant “natural” rate of unemployment does not exist.

This means we cannot absolve central bankers from charges that their anti-inflation policies contribute to higher unemployment. They have already done so. Our estimates suggest that overly restrictive macro policies in the OECD countries have actually and unnecessarily thrown millions of workers into unemployment by a policy-induced decline in productivity and output growth. This self-inflicted damage must rest on the conscience of the economics profession.