Trickle-down, with the emphasis on “trickle” Since the turn of the Millennium, a torrent of corporate tax cuts has resulted in a trickle of investment growth. This morning Dean Baker objects to: the argument … that reducing corporate taxes will lead to more investment and thereby greater wage growth in the future. The data from the last seventy years show there is no relationship between aggregate profits and investment. As can be seen, there is no evidence that higher corporate profits are associated with an increase in investment. In fact, the peak investment share of GDP was reached in the early 1980s when the after-tax profit share was near its post war low. Investment hit a second peak in 2000, even as the profit share was falling through the second

Topics:

NewDealdemocrat considers the following as important: Featured Stories, Taxes/regulation, US/Global Economics

This could be interesting, too:

Ken Melvin writes A Developed Taste

Joel Eissenberg writes How Tesla makes money

Angry Bear writes True pricing: effects on competition

Angry Bear writes The paradox of economic competition

Trickle-down, with the emphasis on “trickle”

Since the turn of the Millennium, a torrent of corporate tax cuts has resulted in a trickle of investment growth.

This morning Dean Baker objects to:

the argument … that reducing corporate taxes will lead to more investment and thereby greater wage growth in the future. The data from the last seventy years show there is no relationship between aggregate profits and investment.

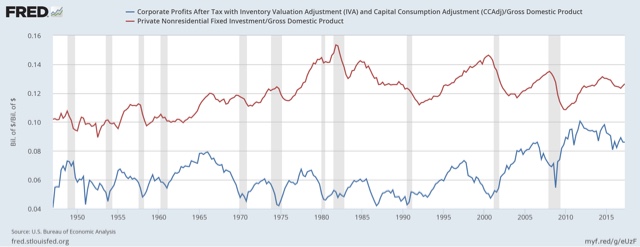

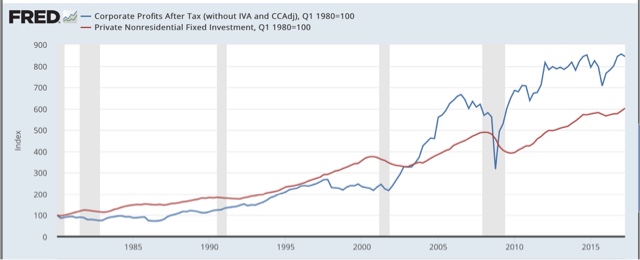

As can be seen, there is no evidence that higher corporate profits are associated with an increase in investment. In fact, the peak investment share of GDP was reached in the early 1980s when the after-tax profit share was near its post war low. Investment hit a second peak in 2000, even as the profit share was falling through the second half of the decade. The profit share rose sharply in the 2000s, even as the investment share stagnated. In short, you need a pretty good imagination to look at this data and think that increasing after-tax profits will somehow cause firms to invest more

I was a little puzzled why Dean didn’t differently scale the two series so it would be easier to see any leading/lagging relationship. Further, since corporate profits are a long leading indicator, and nonresidential fixed investment is more of a coincident indicator, I was pretty sure that there would be a correlation.

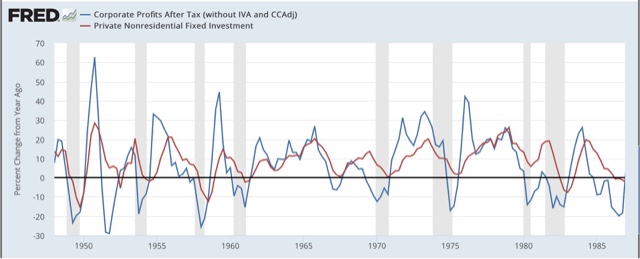

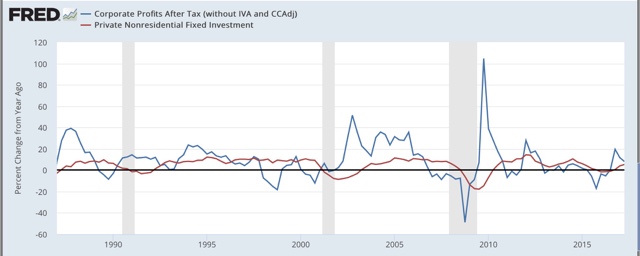

To take a better look, I compared the YoY% changes in each, so that they would scale more equally. Here’s what that looks like divided into 1948-86, and 1986-present:

Sure enough, there is a leading/lagging relationship between the two. That doesn’t mean that an increase in corporate profits *causes* more investment, it just means there is a correlation with a lag.

But also notice that, in the post-WW2 era, the two series move in similar scales: a 40% increase in profits tends to lead to something close to a 40% increase in investment. From the 1980s to the present, a 40% increase in profits leads to a much smaller increase in investment on the order of 10%.

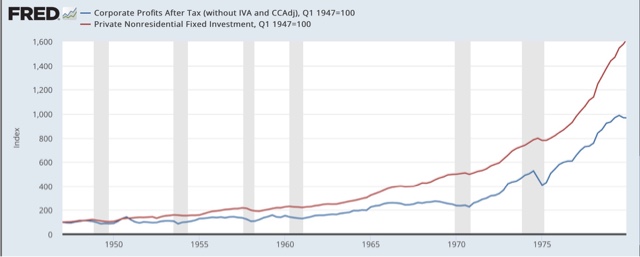

In other words, even if we take the strong case, and assume there is a causative relationship, when we scale the two series more equally, we see that there is a big difference between the post-WW2 era, and the era that began with Ronald Reagan’s presidency:

Simply put, particularly since the turn of the Millennium, a torrential increase in corporate profits only leads to a teaspoonful of investment.

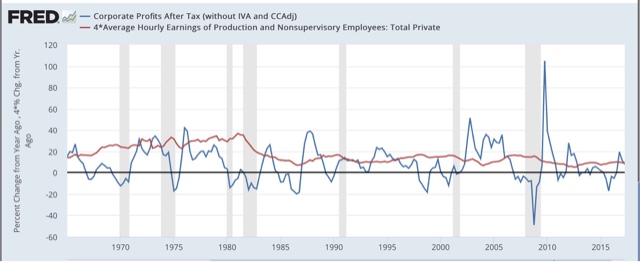

The same is true of wage growth. Since wage growth is pro-cyclical, it tends to peak at the end of expansions, well after corporate profits peak. So there is a leading/lagging relationship on a *cyclical* basis. But *secularly,* corporate profits have increased while wage growth has gradually deflated:

At this stage of the economic expansion, under counter-cyclical policy, if anything we should be trying to run a fiscal surplus. As we have seen above, a corporate tax cut now will do next to nothing for ordinary Americans, and will recklessly blow out the budget at the exact wrong time.

Bottom line: we don’t need even more profits for corporations. We need to increase the share of wage growth relative to corporate profit growth.