Lack of inflation in September consistent with weak demand; real wages increase, but will the pandemic derail the gains? Consumer prices were unchanged in October, both on a seasonally adjusted and unadjusted basis: But while the lack of inflation is good news in isolation, the last two months can also be viewed as a sign of economic weakness – lack of demand – from a recession. Digging a little deeper, for the past 40 years, recessions had typically happened when CPI less energy costs (red) had risen to close to or over 3%/year. We are nowhere near that now (last 15 years shown in graph): Again, note that the YoY% change in inflation has decelerated since the outset of the pandemic, potentially another sign of weakness. On the bright side,

Topics:

NewDealdemocrat considers the following as important: US EConomics, US/Global Economics

This could be interesting, too:

NewDealdemocrat writes JOLTS revisions from Yesterday’s Report

Bill Haskell writes The North American Automobile Industry Waits for Trump and the Gov. to Act

Bill Haskell writes Families Struggle Paying for Child Care While Working

Joel Eissenberg writes Time for Senate Dems to stand up against Trump/Musk

Lack of inflation in September consistent with weak demand; real wages increase, but will the pandemic derail the gains?

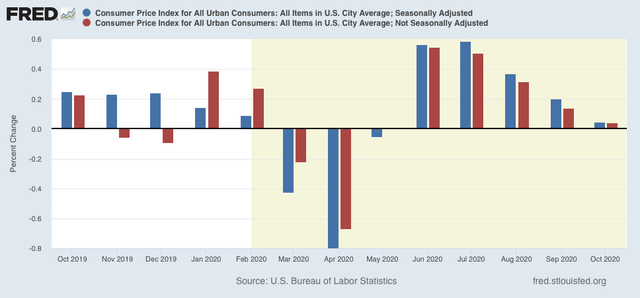

Consumer prices were unchanged in October, both on a seasonally adjusted and unadjusted basis:

But while the lack of inflation is good news in isolation, the last two months can also be viewed as a sign of economic weakness – lack of demand – from a recession.

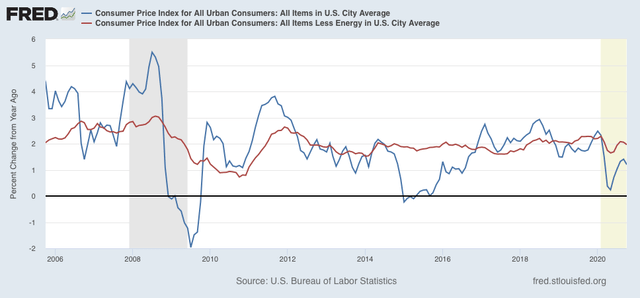

Digging a little deeper, for the past 40 years, recessions had typically happened when CPI less energy costs (red) had risen to close to or over 3%/year. We are nowhere near that now (last 15 years shown in graph):

Again, note that the YoY% change in inflation has decelerated since the outset of the pandemic, potentially another sign of weakness.

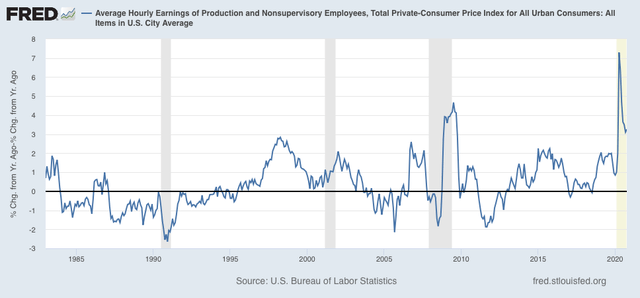

On the bright side, because wages are “stickier” than prices, typically as recessions beat down prices (or at least price increases), in real terms wages rise. That has been the case for the coronavirus recession as well:

It is the “real” buying power of wages among those still securely employed during a recession that is one of the engines that usually restarts growth.

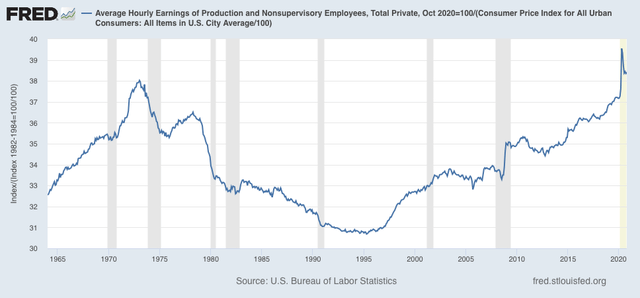

Also as a result, as I’ve noted for the past several months, real hourly wages for non-supervisory workers have finally exceeded their previous 1973 peak, although part of that has been the asymmetric loss of jobs among some of the lower-paid occupations:

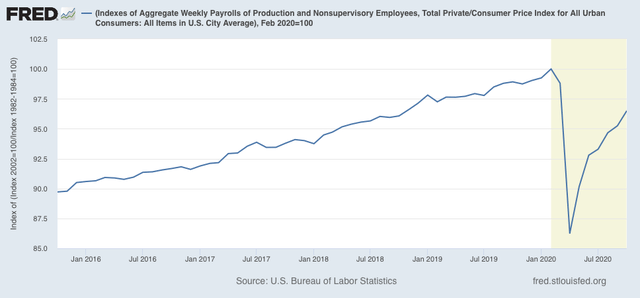

Finally, one of the most telling metrics of the overall health of the middle/working class is that of real aggregate wages. After declining -13.8% from February through April, they have now recovered to a point -3.5% below their peak, approximately at the same level as they were in autumn 2018:

If the rate of gains over the past 4 months were to continue – a *very* open question – aggregate real wages would exceed their February level in about 6 months.

Of course, this data like almost all other economic data remains at the mercy of the course of the pandemic – which is basically out of control in much of the US. It is also very much subject to the public policy that has been stalled in Washington for the past half a year and is going to continue to be stalled until at least January 20.