Scenes from the blockbuster January jobs report 2: revisions do not resolve discrepancies in the reports – by New Deal democrat Yesterday I wrote that the blockbuster January jobs report was essentially the result of two factors: (1) a very low number of potential applicants in the jobs pool with an unemployment rate well under 4% meant that employers were reluctant to let go of workers, which especially impacted the numbers, which particular showed up as (2) the seasonal adjustments expected about 2,000,000 people to be laid off in January, but only 1,600,000 were, as some employers elected to keep Holiday hires on the payroll; also, you can’t fire the people in January that you didn’t hire for seasonal help in October through December.

Topics:

NewDealdemocrat considers the following as important: Hot Topics, January Jobs Report, New Deal Democrat, politics, US EConomics

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Skidelsky writes Lord Skidelsky to ask His Majesty’s Government what is their policy with regard to the Ukraine war following the new policy of the government of the United States of America.

NewDealdemocrat writes JOLTS revisions from Yesterday’s Report

Joel Eissenberg writes No Invading Allies Act

Ken Melvin writes A Developed Taste

Scenes from the blockbuster January jobs report 2: revisions do not resolve discrepancies in the reports

– by New Deal democrat

Yesterday I wrote that the blockbuster January jobs report was essentially the result of two factors: (1) a very low number of potential applicants in the jobs pool with an unemployment rate well under 4% meant that employers were reluctant to let go of workers, which especially impacted the numbers, which particular showed up as (2) the seasonal adjustments expected about 2,000,000 people to be laid off in January, but only 1,600,000 were, as some employers elected to keep Holiday hires on the payroll; also, you can’t fire the people in January that you didn’t hire for seasonal help in October through December.

Today let me deal with the second big reveal in the January report: the 2021 and 2022 revisions, and their effect on the big discordance between the Household and Establishment survey number that began last April.

There were revisions to both the Household and the Employment surveys.

The Household revisions are easy to understand. Every year there is an adjustment for population growth. But instead of spreading that out over the 12 previous months, the Household survey adds it all at once to the January number.

As a result, officially in January per the Household survey, 894,000 more people were employed. But 810,000 of that was caused by the addition of 954,000 to the 2022 population estimate. Only the remaining 84,000 of that was the change from December to January.

One way to reasonably estimate what the Household survey would have looked like in 2022 is to spread out those 810,000 job gains over the past 12 months, which amount to 67,500/month. The below graph does exactly that, adding 67,500 to each Household survey number in 2022, and compares it with the revised Establishment numbers:

Note that adding 67,500 to the January Household number would give us 151,500, about 400,000 below the Establishment number. But more importantly, note that there is still a very large disconnect between the Household numbers, which added 1,810,000 jobs since last March, for an average of 181,000 per month, vs. the Establishment survey’s reported gains of 3,649,000, or 365,000 per month.

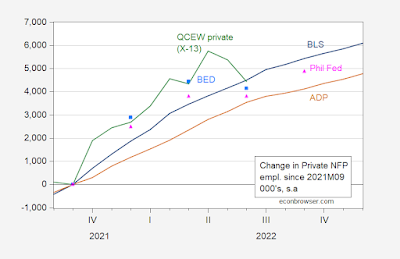

Secondly, in the last several months there has been debate about whether the Household survey has been picking up weakness that was entirely missing in the Establishment survey. Evidence for this was indicated by an estimate from the Philadelphia Fed, based on the QCEW report for Q2 of last year that only 11,000 private sector jobs had been added during that entire 3 month period. This is important because the QCEW is the gold standard for employment reports, consisting of the actual total from 95% of all businesses via unemployment insurance payments. Subsequently the Census Bureau itself updated its “Business Dynamics Survey” through Q2 of last year, which seasonally adjusts about 70% of the QCEW numbers, and reported an outright *loss* of -287,000 jobs in the private sector during that period.

To best show this, here is a graph from Prof. Menzie Shinn of Econbrowser, comparing the unrevised Establishment survey reports, with the Household reports, the QCEW gains normalized to the same number in 2021 and applying his estimate of seasonal adjustments, the Philadelphia Fed estimates, and the Business Dynamics Survey result:

Note that Prof. Shinn’s method of seasonally adjusting renewers a very different result from both the Philadelphia Fed and the Census Bureau itself in the BDS.

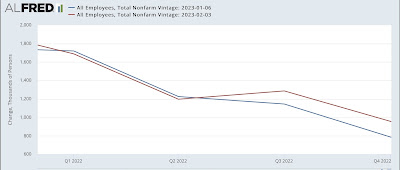

So at first blush it is very surprising that the 2022 benchmark revisions to the Establishment survey *added* 457,000 jobs to the previous results, and while Q2 2022 numbers were revised downward by -59,000, still showed 1,047,000 jobs gained during that Quarter, as shown in the graph below:

So, did people mistake the message of the Q2 QCEW? As Dean Baker wrote, apparently not:

“The QCEW relies on unemployment insurance filings, which give a virtual census of payroll employment. The establishment survey is benchmarked to QCEW annually, but the benchmark takes place with the January data, using the QCEW data from the prior year’s first quarter. The QCEW data from March 2022 were just included in the establishment survey, increasing employment growth in the year from March 2021 to March 2022 by 568,000.”

In other words, while the strong QCEW data from Q1 2022 was included in the benchmark revisions, the weak data from Q2 was not.

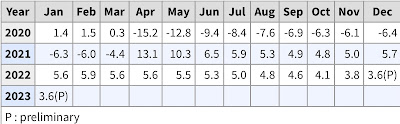

This shows up dramatically if we compare the YoY% changes in payrolls growth as measured by the QCEW census, vs. the same metric from the Establishment survey. This is the best way to measure because the one drawback of the QCEW is that, even though it is comprehensive, it is not seasonally adjusted. But that doesn’t affect YoY comparisons.

Here is the YoY% change monthly in the QCEW survey through its most recent report for Q2 2022:

And here is the same thing for private nonfarm payrolls:

Comparing the YoY QCEW report through Q1 2022 with private payrolls, the former was up 7.2m jobs and 5.1%, and the latter up 6.9m and 5.6%. While the % change is still off, the total number is close, and on par with variances in the past. The median monthly difference between the two measures is 0.3%, and the mean is 0.5%.

For Q2, YoY the QCEW was up 5.7m and 4.0%, while private payrolls after revisions were up 6.3m and 5.3%. This is a very large difference. The median difference is 0.8%, and the mean is 0.9%.

My expectation is that the difference will be resolved in favor of the much more comprehensive final QCEW figures once they are in. Additionally, we’ll get preliminary figures for the Q3 2022 QCEW numbers later this month, and this will tell us if the divergence continued.

In short, even with the revisions there is a large difference between big Establishment gains in the last 9 months of 2022 vs. tepid ones in the Household report. And the divergence between the Establishment sample and the comprehensive QCEW and BDS jobs census figures for Q2 was not taken into account in the January revisions, and remains.