Reversing extreme wealth concentration means going after property income. Originally Published at Wealth Economics Economists and pundits have been cheered of late by the labor-share increase during the first couple of years of the Covid era. And even, for a moment, lower-income workers were making progress vs higher-income folks. This is good news. In the long view, though, these happy developments are just a minor blip in the half-century decline post-Reagan, which drove off a cliff from the Dot-Bomb through the Global Financial Crisis. These measures are meaningful, but they don’t put across the sheer volume and magnitude of the disparity, and the shift. And they don’t impart the end result: extreme and increasingly concentrated

Topics:

Steve Roth considers the following as important: Labor Income, property income, US EConomics, US/Global Economics, wealth

This could be interesting, too:

NewDealdemocrat writes JOLTS revisions from Yesterday’s Report

Bill Haskell writes The North American Automobile Industry Waits for Trump and the Gov. to Act

Bill Haskell writes Families Struggle Paying for Child Care While Working

Joel Eissenberg writes Time for Senate Dems to stand up against Trump/Musk

Reversing extreme wealth concentration means going after property income.

Originally Published at Wealth Economics

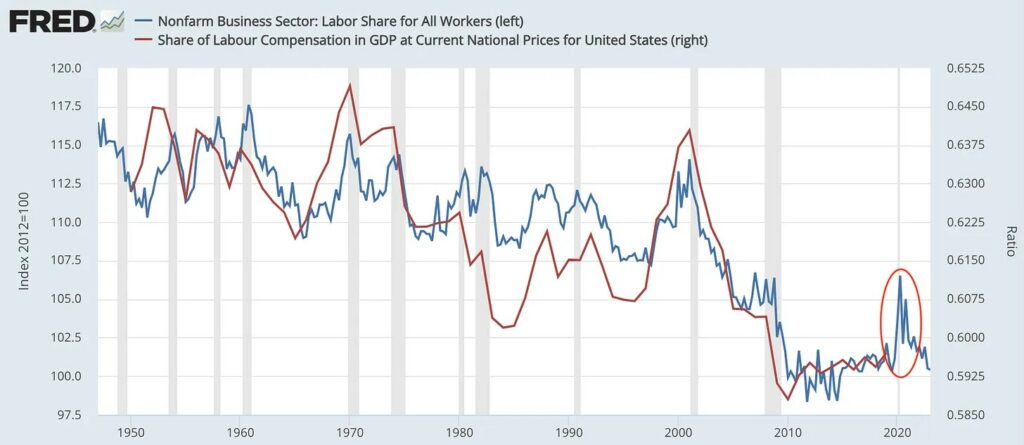

Economists and pundits have been cheered of late by the labor-share increase during the first couple of years of the Covid era. And even, for a moment, lower-income workers were making progress vs higher-income folks. This is good news. In the long view, though, these happy developments are just a minor blip in the half-century decline post-Reagan, which drove off a cliff from the Dot-Bomb through the Global Financial Crisis.

These measures are meaningful, but they don’t put across the sheer volume and magnitude of the disparity, and the shift. And they don’t impart the end result: extreme and increasingly concentrated wealth, with all its pernicious effects.

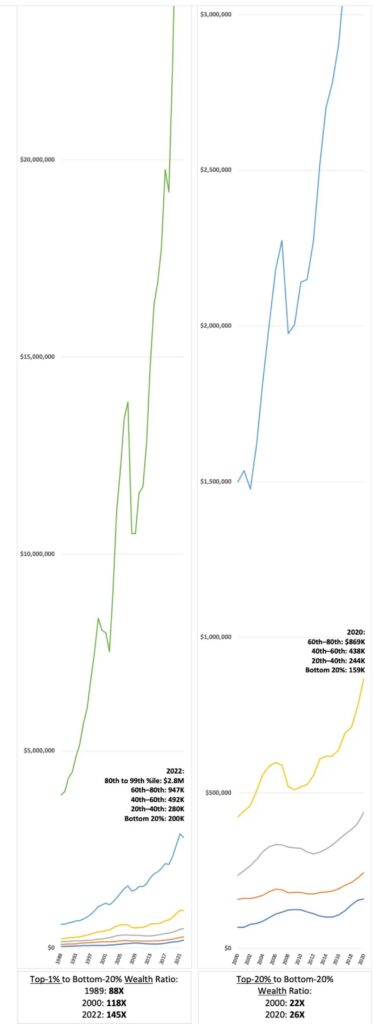

The most eye-popping results are for the top 1%, in the first graph spanning 34 years. It needs to be very tall just to make the lower-quintile lines visible. An average top-1% household has 145 times as much wealth as a bottom-20% household. That’s almost doubled from the 1989 ratio. (Note that top-percentile wealth barely stumbled in the dot-bomb. The epochal GFC collapse was tougher; top-1% wealth took a whole six years to bounce back.)

The second graph rolls top-1% wealth into the top 20%, and runs from 2000-2020, so it’s comparable to the next three graphs. The top quintile still made impressive wealth gains in that picture, increasing the top vs bottom ratio from 22X to 26X.

But where did all that top-end wealth come from? From “income,” natch.

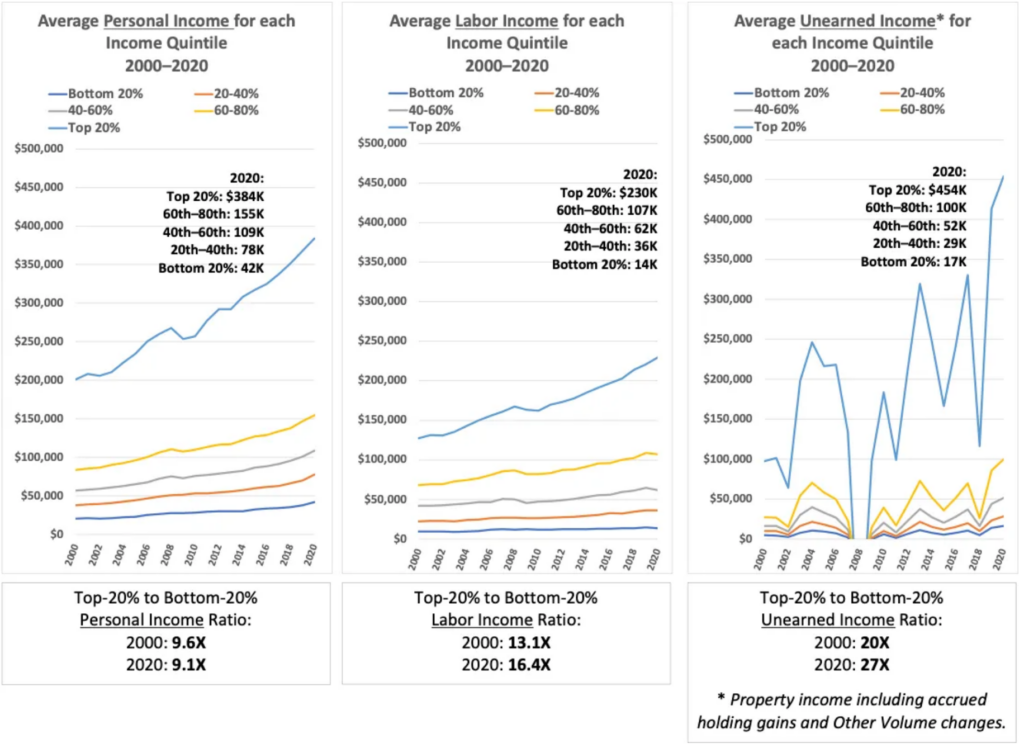

These graphs obviously show much smaller numbers. They’re annual flows, not accumulated stocks. But the ratios at the bottom are meaningfully comparable.

The first thing to notice is how small top labor income is, comparatively. That income is pretty concentrated with its 16.4X ratio, and that ratio has increased quite a lot, but the sheer (small) magnitude can’t explain much of the extreme wealth concentration we’ve seen.

Personal income (earned income + “primary” property income + net transfers) seems to show a slight ratio improvement over 21 years, from 9.6X to 9.1X. But that’s an artifact of big 2020 covid transfer payments juicing up personal income. The 2019 ratio was 9.7X. Personal-income distribution is much more “equal” than other measures (largely due to transfers), and it hasn’t changed much over two decades.

Unearned income does much more to explain where all the top-quintile wealth came from. It’s a large flow, and it skews heavily to the top quintile — a 27X ratio, much increased from 2020’s 20X.

This measure of total property income includes additional property income that’s absent and ignored in “primary” property income, hence in personal income: accrued holding gains, plus other changes in volume.1 This total measure is volatile, but over six decades, accumulated holding gains have only seen one significant drawdown, in 2008.

The point here is that, welcome as they are, changes to earned labor income are a very weak lever for shifting the massive concentration of wealth. If progressives want to reverse that concentration of wealth — and power — the focus will have to be on seizing the unearned property income. And the wealth.

Notes:

1 Add the additional property income to personal income, and you’ve got total or comprehensive income, which fully explains wealth accumulation. Absent that, the arithmetic doesn’t add up. Not even close. Holding gains alone comprise 39% of total property income. Unless you’re predicting the Mother Of All asset-market meltdowns, and you think the asset drawdown will be permanent, those holding gains are very, very real wealth indeed.