Summary:

Guest post by Paddy Carter. Jeremy Corbyn’s People’s QE offers the alluring prospect of spending more without borrowing more. Which is just the ticket, if you want to replace austerity with largesse, and cut the deficit to boot. Sadly, this appealing miracle cure is pure snake oil (although there is, perhaps, a version of the idea which might be helpful, if substantially less miraculous). The basic idea behind People’s QE is to finance public spending by printing money. This is actually something that happens all the time, and it is by understanding how, and why, that we shall see why People’s QE, as sold, is an empty promise. As the real economy grows, the money supply has to keep up. Suppose we wanted zero inflation then, as a first approximation, we would expect the money supply to grow at the same rate as the real economy. If the economy grows at 2 per cent a year and base money (reserves and bank notes) grows at the same rate as the broad money supply (debit accounts etc.) then the newly printed money implied by expanding base money at 2 per cent is government revenue. The word for this is seignorage and for PQE to enable spending without borrowing, it must increase the long-run rate of seignorage. Over the short run, the base money supply ebbs and flows as the Bank of England (BoE) goes about its business.

Topics:

Frances Coppola considers the following as important: Bank of England, Corbyn, fiscal policy, Monetary Policy, QE

This could be interesting, too:

Guest post by Paddy Carter. Jeremy Corbyn’s People’s QE offers the alluring prospect of spending more without borrowing more. Which is just the ticket, if you want to replace austerity with largesse, and cut the deficit to boot. Sadly, this appealing miracle cure is pure snake oil (although there is, perhaps, a version of the idea which might be helpful, if substantially less miraculous). The basic idea behind People’s QE is to finance public spending by printing money. This is actually something that happens all the time, and it is by understanding how, and why, that we shall see why People’s QE, as sold, is an empty promise. As the real economy grows, the money supply has to keep up. Suppose we wanted zero inflation then, as a first approximation, we would expect the money supply to grow at the same rate as the real economy. If the economy grows at 2 per cent a year and base money (reserves and bank notes) grows at the same rate as the broad money supply (debit accounts etc.) then the newly printed money implied by expanding base money at 2 per cent is government revenue. The word for this is seignorage and for PQE to enable spending without borrowing, it must increase the long-run rate of seignorage. Over the short run, the base money supply ebbs and flows as the Bank of England (BoE) goes about its business.

Topics:

Frances Coppola considers the following as important: Bank of England, Corbyn, fiscal policy, Monetary Policy, QE

This could be interesting, too:

Angry Bear writes A Fiscal Policy in a Global Context?

Matias Vernengo writes Very brief note on the Brazilian real and the fiscal package

Angry Bear writes Open Thread January 4 2024 overly “restrictive” monetary policy

Hasan Cömert & T. Sabri Öncü writes Monetary Policy Debates in the Age of Deglobalisation: the Turkish Experiment – III

Guest post by Paddy Carter.

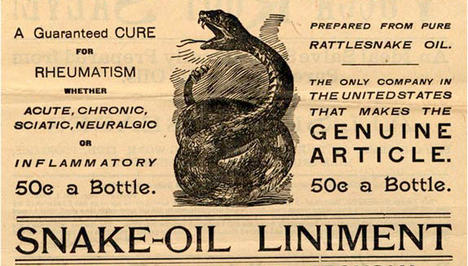

Jeremy Corbyn’s People’s QE offers the alluring prospect of spending more without borrowing more. Which is just the ticket, if you want to replace austerity with largesse, and cut the deficit to boot. Sadly, this appealing miracle cure is pure snake oil (although there is, perhaps, a version of the idea which might be helpful, if substantially less miraculous).

The basic idea behind People’s QE is to finance public spending by printing money. This is actually something that happens all the time, and it is by understanding how, and why, that we shall see why People’s QE, as sold, is an empty promise.

As the real economy grows, the money supply has to keep up. Suppose we wanted zero inflation then, as a first approximation, we would expect the money supply to grow at the same rate as the real economy. If the economy grows at 2 per cent a year and base money (reserves and bank notes) grows at the same rate as the broad money supply (debit accounts etc.) then the newly printed money implied by expanding base money at 2 per cent is government revenue. The word for this is seignorage and for PQE to enable spending without borrowing, it must increase the long-run rate of seignorage.

Over the short run, the base money supply ebbs and flows as the Bank of England (BoE) goes about its business. The BoE does not directly target the money supply, instead it sets the interest rate and lets the money supply do whatever is needed to meet demand at that rate. The process is rather convoluted and involves banks setting targets for the amount of money on reserve over a certain period. There is not a neat relationship between the interest rate and money supply growth, so you cannot say that when the interest rate is low the money supply is expanding, and vice versa. But you would not go far wrong to think that when the interest rate is stimulating the economy, the rate of seignorage grows, and shrinks when monetary policy is tightened (potentially becoming negative).

And here’s why People’s QE (PQE) is snake oil. So long as the BoE is still targeting inflation, it will still be pushing and pulling money in and out of the system, as required to meet demand for money at the interest rate it has set. If the BoE is still targeting inflation, then whatever money PQE puts into the economy on one hand, the BoE is going to be taking out with the other. Or, if the BoE happens not to take the money out, that implies it would have been putting it in, anyway. And that means that over the long run the rate of seignorage, or the extent to which the government is able to spend without borrowing, is not affected by PQE.

But why would the BoE want to remove whatever money PQE puts in? After all, we just put £375bn of freshly printed money into the economy, without causing inflation. Conventional QE is an entirely different animal from PQE. Conventional QE merely swapped one asset (bonds) for another (cash). This did not much affect banks’ ability to lend nor the demand for borrowing, so that cash has merely accumulated on reserve. Conventional QE works by changing - only by a little - the returns on assets so that they become a little less attractive and spending relatively more so. This probably only had a modest impact on the economy. PQE, in contrast, is there to directly finance spending, pay wages, purchase goods. The whole point is to boost aggregate demand. For PQE inflation is a feature, not a bug. Now it’s true that there may be some slack in the economy and some of the things the envisaged PQE-financed National Development Bank would do might raise productive capacity, so there might be some scope to raise demand without inflationary pressure. But step beyond that and either the BoE would neutralise it, or, if prevented from doing so, we’d get inflation. Judging by campaign rhetoric, I think we can expect a Corbyn administration would err on the side of too much spending.

It is not clear exactly how PQE would be implemented. The most important question is whether it would be a countercyclical tool in the hands of the BoE, or something the government uses whenever it wants to finance expenditure. Richard Murphy has suggested the Bank governor would be fired if he tried to block the policy. If, somehow, the flow of money fed into the system is forced above whatever is consistent with the BoE setting its interest rate to hit its inflation target, then we can expect inflation to rise above target. The government could spend without borrowing, if it decided to abandon the current arrangements for inflation targeting. In the extreme, if a Corbyn administration opened the monetary taps every time it thought unemployment was too high and investment too low (i.e. all the time), and neutered the BoE’s ability to offset, then warnings about inflation might start to look warranted.

None of this says we currently have the best possible system. The failure to exploit low interest rates to finance infrastructure investment during the great depression has been particularly egregious. Perhaps a version of PQE could have a role, as a countercyclical tool in the hands of the BoE, in solving that problem and combating deflationary pressure. In theory PQE is entirely unnecessary and governments can finance investment during downturns by borrowing when rates are low. In practice, some short-run seigniorage earmarked for public investments might help the system overcome its reluctance to do so and deliver countercyclical fiscal policy via a monetary backdoor. But that’s not what Corbyn is selling.

_________________________________________________________________________________

Paddy Carter is really a development economist but has been brainwashed by years of teaching undergraduate macroeconomics and absorbing more by osmosis, briefly having had an office down the hall from Tony Yates. A long time ago he was a journalist. His academic research can be found here: https://sites.google.com/site/ paddycarter/