The ever-optimistic OBR has some encouraging forecasts for interest rates and global government bond yields: Well, ok, they were rather more encouraging in November than they are now. The uplift was supposed to start ANY DAY NOW, but there has been an interruption to normal service. Leaves on the line, perhaps. Or the wrong sort of snow.The trouble is, the OBR has a long record of hockey-stick forecasting. Not that it is unique in having a noticeable bias to the upside: If ever there were evidence that economic forecasting owes more to magic than science, it is this pair of charts. Markets expected that interest rates would start rising in 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014......it is now 2016 and markets are beginning to wonder if they will ever rise. There is a feeble uplift pencilled in for 2018, and the ghost of a suggestion that there could even be a rate cut this year. The runes have failed, not once but repeatedly. Sack the shamans.Why the runes have failed is not at all clear. The UK's disastrous productivity record and the ongoing weakness in policy rates (and by extension, bond yields) appear correlated, but that does not mean that one causes the other - indeed as productivity is a residual, it seems unlikely that it has any causative effect. Rather, I think both should be seen as responding to an underlying problem.

Topics:

Frances Coppola considers the following as important: Debt, demand, helicopter drop, markets, negative rates, QE, sovereign debt

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Skidelsky writes Britain’s Illusory Fiscal Black Hole

Michael Hudson writes Gold as the Peace Currency

Angry Bear writes The Rising Burden of Government Debt

Angry Bear writes US Debt, Problems, and Fixes

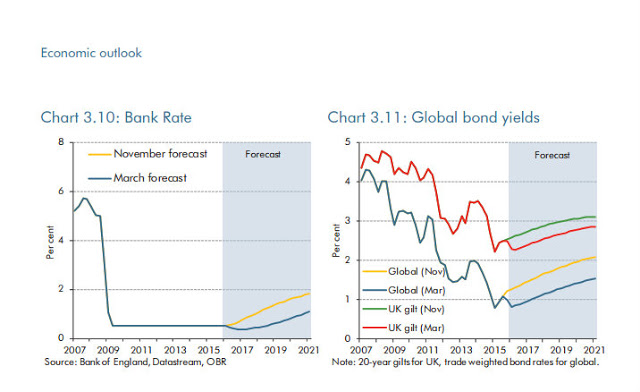

Well, ok, they were rather more encouraging in November than they are now. The uplift was supposed to start ANY DAY NOW, but there has been an interruption to normal service. Leaves on the line, perhaps. Or the wrong sort of snow.

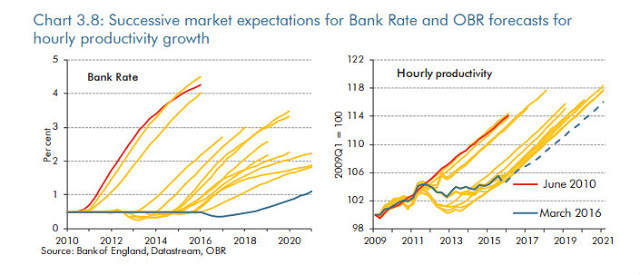

The trouble is, the OBR has a long record of hockey-stick forecasting. Not that it is unique in having a noticeable bias to the upside:

If ever there were evidence that economic forecasting owes more to magic than science, it is this pair of charts. Markets expected that interest rates would start rising in 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014......it is now 2016 and markets are beginning to wonder if they will ever rise. There is a feeble uplift pencilled in for 2018, and the ghost of a suggestion that there could even be a rate cut this year. The runes have failed, not once but repeatedly. Sack the shamans.Why the runes have failed is not at all clear. The UK's disastrous productivity record and the ongoing weakness in policy rates (and by extension, bond yields) appear correlated, but that does not mean that one causes the other - indeed as productivity is a residual, it seems unlikely that it has any causative effect. Rather, I think both should be seen as responding to an underlying problem. But what is the problem?

Over at Morgan Stanley, Matthew Hornbach has an idea what might be going on. He's talking about the US, but of course persistent downwards adjustment to interest rate, bond yield and output forecasts is not purely a UK phenomenon: the entire Western world is suffering from limp outturns. In a research note (h/t Jamie McGeever of Reuters), Hornbach speaks about his Japanese experience, and how it relates to Morgan Stanley's forecasts for US bond yields:

If Hornbach is right, the "widowmaker" is no longer solely Japanese. Shorting the bonds of any Western country with an activist central bank and a poor economic outlook is a mug's game. The OBR's forecasts for global bond yields are, once again, over-optimistic. There is little reason to assume that the downwards trend of bond yields will reverse any time soon, and considerable reason to think that yields will go substantially more negative.We see 10-year Treasury yields ending 2016 at 1.75%, near current levels. But we see even lower yields catching investors off guard in the middle quarters of the year. The lessons I learned in Japan leave me comfortable with this outlook. Years of staring at low JGB yields certainly immunized me from the sticker shock associated with low Treasury yields. And I know that investors tried to short JGBs mostly without success for years.

Hornbach has, of course, been reading Koo. Not everyone agrees with Koo's prescription for solving Japanese-style stagnation: but there is now broad agreement about his diagnosis. With few exceptions, the Western world is in a balance sheet recession, in which demand for credit becomes inelastic with regard to price. Even deeply negative rates don't significantly increase credit demand.

Negative rate aficionados find this incomprehensible. Why wouldn't people borrow if they were paid to do so? But when balance sheets are highly leveraged, people will not take on more debt EVEN IF interest rates turn negative, because they believe that interest rates will eventually rise and they will then have problems refinancing the debt at affordable rates. Deeply negative rates as a temporary shock to kickstart credit demand founder on the rock of Ricardian equivalence. (Miles Kimball, this is my response to your question!)

This enables us to identify what the "underlying problem" is. The desire of the private sector to avoid taking on debt at any price is a significant squeeze on aggregate demand, which reveals itself as stubbornly low inflation and poor growth. It inevitably puts downwards pressure on sovereign bond yields:

So what to do about this? Well, spend some money, really:As our economists have suggested before, the world is dealing with demand deficiency. The decline in government bond yields globally suggests simply that the deficiency is growing.

If the private sector is not willing or able to borrow and spend enough to generate a sustainable inflation impulse, despite the increasingly lower costs to do so, then the public sector should step in to prevent deflation.

Whether this "borrowing and spending" takes the form of fiscal stimulus or central bank intervention is irrelevant. Somehow, more money has to get into the economy.Ultimately, that is the message from government bond markets today. The public sector, to the extent it can control its own money supply, needs to borrow and spend because the private sector is not spending enough. The situation has gotten so extreme that investors are willing to pay certain governments to do just that. In Japan, with a negative yield on 10-year JGBs, investors are paying the government to borrow out to a 10-year term and spend. If the public sector ignores these types of messages on a global scale and private demand globally remains deficient, those same investors will accept still lower yields on government bonds outside of Japan – our base case for the rest of 2016.

Maybe it is time we stopped our ears to the siren voices that lure us on to the rocks of economic stagnation by singing about the virtues of fiscal consolidation, and started listening to the song of the bond markets. Bond vigilantes are chimeras: the bond markets want more of the debt of Western countries with activist central banks, not less.

Fiscal consolidation is the wrong medicine in a balance sheet recession. It removes from the economy money needed by the private sector to repair balance sheets: central bank monetary stimulus is weakened by fiscal consolidation, because the government siphons the water out of the tub nearly as fast as the central bank puts it in. And monetary stimulus which primarily benefits the rich, such as QE, is inadequate anyway. As Nouriel Roubini says, money needs to get into the hands of people who will spend it, not save it:

Break out those helicopters.Second, QE could evolve into “helicopter drop” of money or direct monetary financing by central banks of larger fiscal deficits. Indeed, the recent market buzz has been about the benefits of permanent monetization of public deficits and debt. Moreover, while QE has benefited holders of financial assets by boosting the prices of stocks, bonds, and real estate, it has also fueled rising inequality. A helicopter drop (through tax cuts or transfers financed by newly printed money) would put money directly into the hands of households, boosting consumption.

Related reading:

All QE is "people's QE", just not the right people - The Exchange, FT

Rethinking government debt

Helicopters are easy to fly - Simon Wren-Lewis