Sterling is falling. Predictably, the financial press describe its slide as a "pounding" and gleefully tell us that sterling is the worst-performing currency after the Argentinian peso.But some people are cheering. Falling sterling is good for exports, isn't it? So if the pound keeps falling, the UK's large trade deficit will start to shrink, reducing the UK's dependence on external financing and hence its vulnerability to a "sudden stop".Sadly, it's not that simple. Falling sterling is not an unalloyed good for exporters. The real effect is considerably more nuanced, and over the longer term, not necessarily positive.As an exporter myself, I am certainly enjoying the pound's fall. These days, most of my income is in US dollars. This is how GBRUSD has performed this year: Since my income is in dollars but my outgoings are in sterling, I've had a pretty substantial pay rise.But my chickens will come home to roost shortly. The price of petrol is about to rise by 5p a litre because of sterling's fall. That is a real cost which I cannot avoid, since my singing teaching requires use of a car. My income is still rising, but my profits will be diminished by rising costs. When the fall in sterling affects other business costs too, such as air fares, train fares, hotels and subsistence, I might be looking at a rather substantial rise in my costs.

Topics:

Frances Coppola considers the following as important: Brexit, currency, trade

This could be interesting, too:

Frances Coppola writes Trade lunacy is back

Angry Bear writes Policies Shifted Trade from China?

Frances Coppola writes The entire crypto ecosystem is a ponzi

Frances Coppola writes There’s no such thing as a safe stablecoin

But some people are cheering. Falling sterling is good for exports, isn't it? So if the pound keeps falling, the UK's large trade deficit will start to shrink, reducing the UK's dependence on external financing and hence its vulnerability to a "sudden stop".

Sadly, it's not that simple. Falling sterling is not an unalloyed good for exporters. The real effect is considerably more nuanced, and over the longer term, not necessarily positive.

As an exporter myself, I am certainly enjoying the pound's fall. These days, most of my income is in US dollars. This is how GBRUSD has performed this year:

Since my income is in dollars but my outgoings are in sterling, I've had a pretty substantial pay rise.

But my chickens will come home to roost shortly. The price of petrol is about to rise by 5p a litre because of sterling's fall. That is a real cost which I cannot avoid, since my singing teaching requires use of a car. My income is still rising, but my profits will be diminished by rising costs. When the fall in sterling affects other business costs too, such as air fares, train fares, hotels and subsistence, I might be looking at a rather substantial rise in my costs.

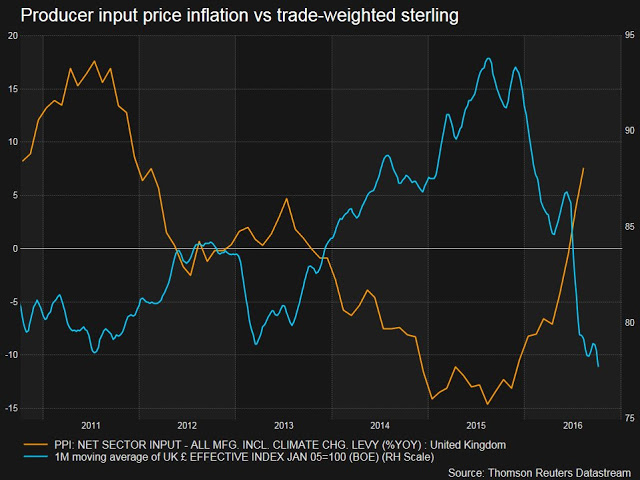

Business costs are already rising for exporters whose business inputs are raw materials and intermediate goods. And all of us face higher energy and transport costs, because the UK is dependent on imports of oil and natural gas, and those are priced in dollars and euros.

This chart from Reuters shows that producer price inflation is already rising fast:

The net gain for exporters is still positive, but energy price rises have yet to bite. Exactly how much of the income improvement due to currency effects will be wiped out by rising input costs remains to be seen. For some exporters - especially in the UK's fragile manufacturing sector - it could even be a wash.

And that is before we get to the effect of inflation on labour costs. I face rising prices for food, clothes and other consumer goods. As a sole trader, my profits are my income, so I will shortly face a reduction in my disposable income as inflation eats into my profits. But businesses with employees are likely to face demands for wage increases. The businesses most affected will be those that have skill shortages, powerful unions and/or need seasonal labour that could now be hard to come by, because the weak pound makes temporary migration from overseas less attractive.

The fact is that the UK is an import-dependent economy, and sterling's fall makes imports more expensive. For businesses, this means higher costs. For households, this means lower living standards, at least in the short term. As Paul Krugman says, sterling's depreciation makes Britain poorer.

Over the longer term, we might find that higher import prices encourage the growth of domestic industries producing goods and services that can substitute for expensive imports. But there are two obstacles to this.

The first is the UK's dependence on imports for energy. High energy prices due to sterling's weakness will put downward pressure on domestic demand, simply because people will prioritise heating, lighting and fuel over consumables. We've seen this before: high oil prices in 2010-13 were a major reason for the failure of the UK's recovery after the financial crisis. There is no reason to suppose that this time would be different.

The same energy price constraint bites on domestic businesses, which would face higher costs than their overseas competitors. Given this, would they really be able to undercut importers by enough to generate widespread substitution effects - especially if, after a hard Brexit, the Government decided to cut import tariffs unilaterally, as some have suggested?

We need substantial investment in replacement energy sources as North Sea Oil dries up. The UK has neglected this investment over many years now, and it is about to pay the price for this folly. Replacement energy sources take quite some time to come on stream, and during that time the UK will face higher energy prices and associated inflation, to the detriment of households, businesses and the economy as a whole.

The second obstacle is inward investment. The UK has historically been a favourite destination for foreign investors, attracting more capital investment than anywhere else in Europe. This is no doubt due to its dominant financial sector, deep and liquid capital markets, and enormous supply of investment assets. Being a favoured investment destination is of course, something of a double-edged sword: the UK's yawning current account deficit is to a considerable extent due to its attractiveness to foreign capital (the capital account is the mirror image of the current account, so a capital account surplus is matched by a current account deficit). But if the UK is to develop new domestic and export businesses, it will need inward investment.

Some people seem to think that the current starry performance of the FTSE 100 indicates that inward investment into the UK is holding up. Sadly, this is not true. The falling currency is a clear sign that investment is leaving the UK, as are rising yields on gilts. At present, all the signs are that investors are becoming exceedingly wary of investing in the UK.

All of this leads me to conclude that those who think a falling pound will somehow bring about radical rebalancing of the economy away from financial services and towards revitalisation of manufacturing are taking far too simplistic a view. The UK economy is highly financialised and largely consists of service industries. Manufacturing is still about 14% of the economy, but the heavy manufacturing of the past is gone: UK manufacturing now is specialised, highly skilled and makes extensive use of imports. Even were foreign investment to hold up, it would take a very long time for the UK to expand manufacturing to the level of say Germany. It's worth remembering that a 25% devaluation in 2008-9 made little significant difference to manufacturing production or goods exports. As I said above, why would this time be different?

Sterling's fall should be regarded as at most a short-term monetary stimulus to the economy. The UK now has the loosest monetary policy in the G7 (eat your heart out, Kuroda-san!). This is in large measure the reason for the apparent calm in the UK economy, along with buoyant consumer confidence (which is no surprise, since the great British public apparently believe that leaving the EU and restricting immigration will make them more prosperous). It creates a breathing space in which the Government can devise a sensible approach to leaving the EU. But if it is to foster lasting change, it must be partnered with a radical fiscal response involving substantial infrastructure investment, a properly funded business bank and a realistic industrial strategy. Without these, sterling's fall will simply herald the dawning of a poorer, meaner future for Britain.

Related reading:

Brexit is making Britons poorer and meaner - The Economist

UK's trade-weighted currency index slumps to historic new low on hard Brexit fears - The Independent

Brexit and Britain's Dutch disease - FT Alphaville