Some people have been saying that sterling's fall has nothing to do with the Brexit vote. Sterling was already falling before the vote, they say, because of the UK's wide and growing current account deficit. So I thought I would fact check this.Here is the UK's current account deficit since 1987, courtesy of ONS: Well, ok, it has rarely been anywhere near balance in the current century, and it has been trending downwards since 2011.Now let's look at sterling. Here is sterling's trade-weighted exchange rate since 1992, courtesy of the Bank of England (via this House of Commons briefing paper): Umm. The correlation between the current account deficit and the trade-weighted value of sterling appears to be negative. Sterling has been rising since 2011 - until this year.This is actually reasonable. The trade-weighted value of a currency reflects the external performance of the economy. And for a long time now, current account deficits have not been regarded as important for countries with floating exchange rates and independent central banks. So sterling has risen because the UK has been doing well compared to other countries - notably the depressed EU.Breaking down the current account into its component parts shows why the current account and the value of sterling have been negatively correlated.

Topics:

Frances Coppola considers the following as important: Brexit, currency, trade

This could be interesting, too:

Frances Coppola writes Trade lunacy is back

Angry Bear writes Policies Shifted Trade from China?

Frances Coppola writes The entire crypto ecosystem is a ponzi

Frances Coppola writes There’s no such thing as a safe stablecoin

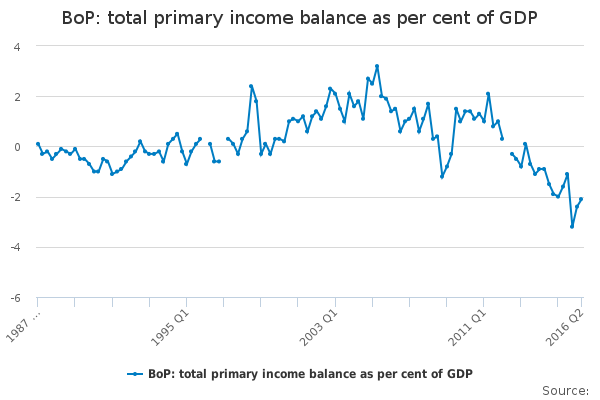

Here is the UK's current account deficit since 1987, courtesy of ONS:

Well, ok, it has rarely been anywhere near balance in the current century, and it has been trending downwards since 2011.

Now let's look at sterling. Here is sterling's trade-weighted exchange rate since 1992, courtesy of the Bank of England (via this House of Commons briefing paper):

Umm. The correlation between the current account deficit and the trade-weighted value of sterling appears to be negative. Sterling has been rising since 2011 - until this year.

This is actually reasonable. The trade-weighted value of a currency reflects the external performance of the economy. And for a long time now, current account deficits have not been regarded as important for countries with floating exchange rates and independent central banks. So sterling has risen because the UK has been doing well compared to other countries - notably the depressed EU.

Breaking down the current account into its component parts shows why the current account and the value of sterling have been negatively correlated. Broadly speaking, the current account is made up of the goods and services trade balance, plus net investment income. The second of these is the income that UK investors earn from their investments abroad minus the income that foreign investors earn on their investments in the UK.

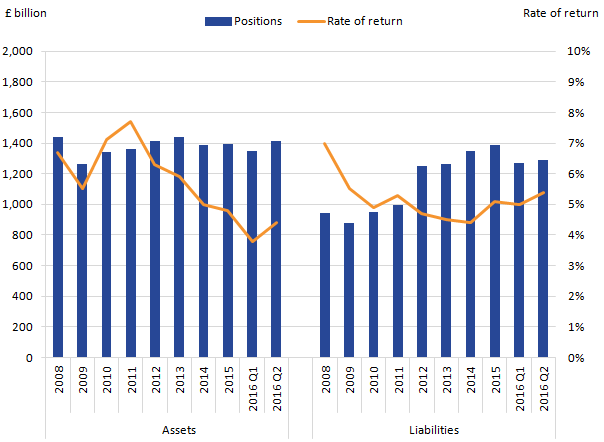

This is what has happened to net investment income (this chart from ONS also includes other financial income, but net investment income is by far the largest component for the UK):

- rising FDI into the UK from 2011 onwards

- higher rates of return on foreign holdings of UK assets than on UK holdings of foreign assets

ONS shows that the trade balance (goods and services) has been pretty stable, though negative, for the whole of this century:

We do see some positive correlation between the trade deficit and the value of sterling, though we can't tell from these charts whether sterling responds to the trade deficit or vice versa - or whether both are responding to something else. But this relationship is dwarfed by the negative correlation of the net investment income balance and the external value of sterling. Basically, people like investing in the UK.

Or they used to. This is what has happened to sterling recently:

This chart could be interpreted as showing a downward trend since the mid-2014 peak. But in fact it is showing reversion to previous levels from the mid-2014 peak, followed by three abrupt falls, one at the beginning of 2016, a larger one in June and a third that has not yet bottomed out. The first of these was due to the market turbulence and worries about bank profitability at the beginning of 2016. But the other two are unquestionably due to the Brexit vote.

The fall of sterling from the beginning of 2016 is even more obvious in the sterling-euro exchange rate:

Sterling rose immediately prior to the EU referendum because of opinion polls suggesting that Remain would win. As the referendum result was announced, it fell sharply against both the US dollar and the euro. Although it stabilised in the summer, it has not recovered from this fall.

A second fall was recently triggered by comments by the Prime Minister, Theresa May, at the Conservative party conference, and the growing likelihood that Britain will leave the EU in the most economically damaging manner possible - a "hard Brexit". Financial markets are particularly concerned at the prospective loss of "passporting rights" to the EU. The UK's position as the world's premier financial centre is under serious threat - and this is reflected in the falling exchange rate of sterling.

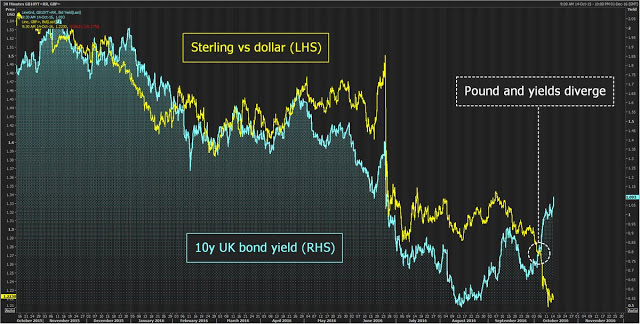

And not just in the sterling exchange rate. Gilts are affected too, as this Reuters chart shows:

After the Brexit vote, gilt yields fell as output forecasts for the UK were slashed and a Bank of England interest rate was priced in. Remember we live in strange times: cutting interest rates is now a negative indicator for an economy, whereas in the inflationary 1970s and 1980s (and indeed in countries such as Russia where inflation has been very high in recent years) it was a positive one.

So used are we to the weirdness of low interest rates that we have forgotten how normal risk pricing works. But we are now being reminded. As it became ever clearer that the UK government was contemplating a hard Brexit, gilt yields started to rise. Now, sterling is falling as well. This is what capital flight looks like in a country that issues its own currency.

Last time we saw capital flight in an advanced economy was the Greek crisis last summer. Everyone remembers Greek bond yields spiking and Target2 imbalances growing as investors and depositors fled from the prospect of Grexit. But there was no currency component to that (well, there was, but you wouldn't find any charts showing the sharply falling implied exchange rate between euros in Greek banks and euros everywhere else). Now, we have capital flight from another advanced country - and this time it is reflected not only in rising yields but in a falling exchange rate. The UK has become a risky place for investors.

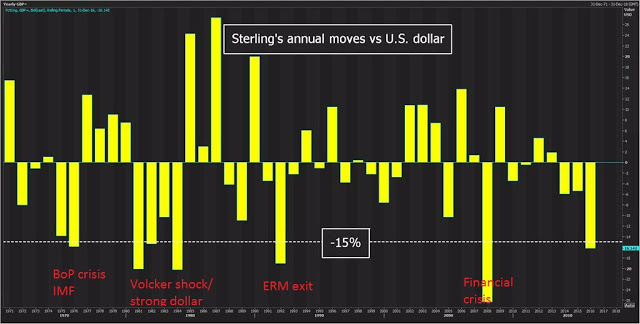

Of course, this might only be a short-term effect. The UK government and the EU authorities are both considering their options at the moment, and once the form that Brexit will take becomes clear and the path defined, both sterling and gilts may well bounce back. Sterling has had larger falls than this, and always bounced back:

But there is, of course, the elephant in the room. All of the sterling shocks in this chart occurred during Britain's membership of what started as the EEC and later became the EU. Indeed, the UK has been a member of the European Union project for the whole of its recent experiment with fully floating exchange rates, which started in 1979 with the lifting of exchange controls. To what extent has EU membership helped to stabilise sterling's exchange rate - and does it now face a more turbulent future? We do not know.

Recently, some have expressed concern about the UK's dependence on external investors - what Mark Carney, quoting Tennessee Williams, called "the kindness of strangers". This is because the UK has both a current account deficit and a fiscal deficit: if both deficits are dependent on external financing, a "sudden stop" can force a very sharp fiscal adjustment and a rapid, highly damaging fall in GDP. There is an outside chance that the current combination of falling currency and rising gilt yields could be the start of a "sudden stop". However, the Bank of England's staff blog recently looked at the financing of the UK's twin deficits and concluded that the fiscal deficit, at any rate, was largely domestically financed so was not in any immediate danger. The current account deficit of course could be subject to a wrenching adjustment if investors fled, although FDI generally tends to be fairly stable. But the two deficits are largely separately financed, so there is little danger of the sort of toxic feedback loop that can ultimately lead to economic collapse and debt default.

What does seem likely is that the net interest income deficit will close, not because returns for UK investors in foreign assets improve but because returns for foreign investors in the UK will now fall due to lower interest rates, QE and a poorer growth outlook. FDI, too, seems likely to decline, though perhaps gradually. No doubt those who are obsessed with current accounts will cheer as the net interest income deficit shrinks, but I wouldn't regard this form of rebalancing as positive, personally. I'd much rather see net investment income turn positive due to higher returns to UK investors from improved growth in Europe.

And what about that trade deficit in goods and services? Well, that might shrink too. Exports will be flattered a bit by the lower exchange rate, and higher inflation will force UK households and businesses to cut back spending, reducing imports. But in the longer term, the outlook for the trade balance depends on what sort of trade deals the UK can cut.

And that brings me back to where I started. Those who thought the fall in sterling was due to a widening current account deficit have the causation wrong. The current fall in sterling is entirely due to Brexit. And the current account deficit is likely to close because of the effect of Brexit on trade and investment. Brexit will determine the behaviour of every UK metric for the foreseeable future.

Related reading:

Short-run effects of the Brexit shock

The currency effects of Brexit