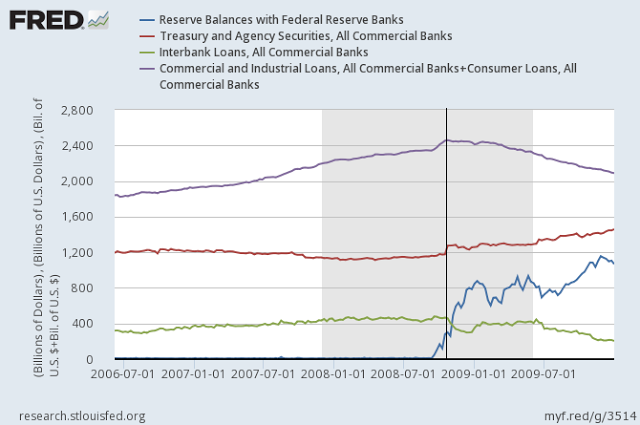

Courtesy of Dr. George Selgin comes this chart from FRED: Dr. Selgin has added a vertical line to indicate when the Fed imposed interest on excess reserves. I don't propose to discuss that here, since I have engaged in an interesting and spirited discussion with Dr. Selgin and others about it on both Forbes and Twitter. I am more interested in what else this chart shows. It is truly fascinating.The first thing to note is the fast rise in bank reserves from the latter part of 2008 onwards (blue line). This is due to emergency liquidity support and distressed asset purchases in the immediate aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, and of course to QE.Unsurprisingly, there was a sharp fall in interbank lending at the time of the crisis. It recovered somewhat early in 2009, but then interbank lending fell again during the main phase of QE1. This is not surprising, since QE1 gave banks more than enough reserves to settle deposit withdrawals. They had no need to borrow from each other.Also during this time there was a considerable decline in bank lending, and a rise in purchases of safe assets (Treasury and Agency securities). Banks appear to have been substituting safe assets for risky ones. Reserves are, of course, safe assets.

Topics:

Frances Coppola considers the following as important: bank lending, banks, Interest rates, QE, safe assets

This could be interesting, too:

Merijn T. Knibbe writes Monetary developments in the Euro Area, september 2024. Quiet.

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Central bank independence — a convenient illusion

Merijn T. Knibbe writes How to deal with inflation?

Matias Vernengo writes Brief note on public debt and interest rates in Brazil

Dr. Selgin has added a vertical line to indicate when the Fed imposed interest on excess reserves. I don't propose to discuss that here, since I have engaged in an interesting and spirited discussion with Dr. Selgin and others about it on both Forbes and Twitter. I am more interested in what else this chart shows. It is truly fascinating.

The first thing to note is the fast rise in bank reserves from the latter part of 2008 onwards (blue line). This is due to emergency liquidity support and distressed asset purchases in the immediate aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, and of course to QE.

Unsurprisingly, there was a sharp fall in interbank lending at the time of the crisis. It recovered somewhat early in 2009, but then interbank lending fell again during the main phase of QE1. This is not surprising, since QE1 gave banks more than enough reserves to settle deposit withdrawals. They had no need to borrow from each other.

Also during this time there was a considerable decline in bank lending, and a rise in purchases of safe assets (Treasury and Agency securities). Banks appear to have been substituting safe assets for risky ones. Reserves are, of course, safe assets. But it looks as if large though the reserves increase was, it wasn't enough to meet the needs of damaged, distressed and risk-averse banks - or substitute for the loss of private sector "safe assets" when the market valuations of private label RMBS and their derivatives collapsed.

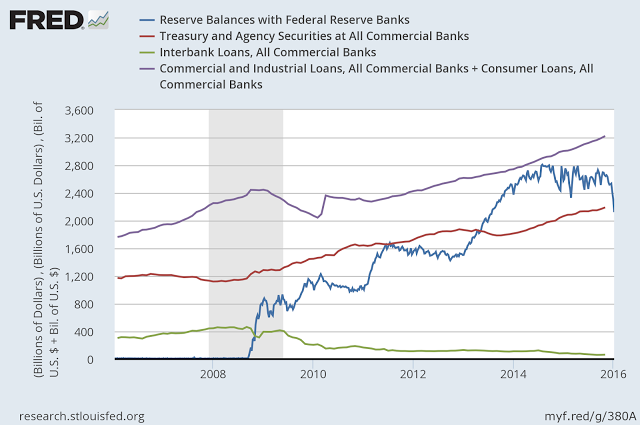

This is interesting enough in itself. But this chart ends in 2009. It only shows the acute phase of the crisis and ensuing recession. I wondered what happened next. So I've created another version of Dr. Selgin's chart, covering the 10 years from January 2006 to January 2016:

This chart is even more interesting than Dr. Selgin's.

Firstly, the three phases of QE can be clearly seen (sharp rises on blue line). Large though the rise in bank reserves was after the financial crisis, it is dwarfed by subsequent rises, particularly QE3.

It also seems that despite the Fed's reinvestment policy, bank reserves decline slightly when QE ends. The sharp drop in reserves at the beginning of 2016 is due to the interest rate rise in December 2015, and in particular, due to overnight repo operations (ONRRP) enabling certain non-banks to deposit funds at the Fed. When non-banks deposit funds at the Fed instead of commercial banks, the effect is a reserve drain.

And the interbank market is all but dead. There is little doubt that this is due to the fact that QE gave bank far more reserves than they actually need to settle deposit withdrawals. If banks don't need to borrow reserves, they can't lend them either: thus, when banks are awash with reserves, the natural level for the Fed Funds Rate is zero, regardless of the state of the economy. The December rise in the Fed Funds Rate was important for what it signalled, not for its economic effects. The principal instrument of monetary policy is now the interest-on-excess-reserves (IOER) rate (or deposit facility rate, if you are an ECB-watcher), which the Fed backs up with ONRRP operations. This will remain the case as long as there are excess reserves in the banking system - which may be for a very long time. Welcome to the new normal.

Should the Fed have raised the IOER rate in December? Well, it had few alternatives. Since the interbank market is dead, it is not possible to raise the Fed Funds Rate by means of open market operations. Raising the IOER rate has the effect of drawing the Fed Funds Rate upwards. The only alternatives are unwinding QE or raising reserve requirements to near 100%. Unwinding QE would be a very sharp monetary tightening, but even more importantly, dumping all those securities on the bond markets would have dramatic and highly destabilising effects. The Fed has wisely ruled this out. The alternative would be raising reserve requirements to near 100%, thus creating artificial shortages of reserves. Do we want to go down the full-reserve-banking route? Some would like this. But the effects on commercial lending need to be considered carefully. At present, the Fed is not opting for this alternative.

In the present circumstances, and absent a major change of policy direction regarding bank regulation, saying that IOER should not have been raised is tantamount to saying that the Fed's December Fed Funds Rate rise was a mistake.

So banks don't lend to each other any more, much. But they do lend to non-banks. Despite QE, IOER and ever-tightening macroprudential regulation, bank lending to households and corporations has been rising steadily since 2012. Unlike Europe, the US fixed its banks quickly. It is clear that excess reserves do not prevent banks lending, and although there is something of a shortage of counterfactual evidence, it seems unlikely that paying IOER at a few basis points has much effect on bank lending either.

But the really interesting feature of this chart is the red line. Bank purchases of Treasury and Agency securities have risen steadily since the financial crisis. The only time this tailed off was during QE3. The combination of large quantities of reserves with higher levels of Treasury and Agency securities suggests that banks have massively de-risked their balance sheets, no doubt under regulatory pressure to shore up capital and liquidity buffers.

We have stopped short of full reserve banking, but banks are far better reserved and have much higher levels of capital than they did before the crisis. The price for this, of course, is increased dependence of banks on the sovereign. Substantial parts of bank balance sheets are now made up of sovereign liabilities, both reserves and securities. For the US, which is the world's premier sovereign reserve currency issuer, this is unlikely to be a problem. But in the Eurozone, bank dependence on sovereign liabilities is a problem - one to which as yet there seems no solution.

The increasing proportion of sovereign liabilities on bank balance sheets - and the intrusive regulation that forces them to adopt such a risk-averse balance sheet management strategy - raises serious questions about the direction of policy. How can we pretend that banks are private sector agents, and demand that any losses are borne only by other private sector agents, when so much of their asset base is made up of public sector liabilities and so many of their activities are subject to public sector regulation?

Far from making banks truly responsible for their own safety, we are creeping ever closer to de facto nationalisation.

Related reading:

Floors and ceilings

The liquidity trap heralds fundamental change

Not all sovereign currency issuers are equal (Rethinking government debt)

The Fed's Brave New Interest Rate World - Forbes

It Was The Financial Crisis That Stopped Banks Lending, Not Interest On Reserves - Forbes

The Fed's IOER Policy Is Not Paying Banks Not To Lend - Forbes

Regulation, regulation, regulation - Pieria

Interest On Reserves (i) - George Selgin

Interest On Reserves (ii) - George Selgin