Eugenics has a bad reputation. Even the word "eugenics" is repugnant to many people, associated as it is with atrocities - forced sterilization programmes in America, for example, and of course the horrors of Nazi Germany. We like to see eugenics as discredited pseudo-science that has been consigned to the dust of history. Never again will we treat people as expendable simply because of their inherited characteristics. But ideas that we discard because of their horrible consequences have a way of returning, dressed up in respectable clothing. Eugenic ideas have existed - and been acted upon - since ancient times. The idea of eliminating those who are, or will be, a burden on society because of disability raises hackles now, but in ancient Rome it was regarded as a public duty. The

Topics:

Frances Coppola considers the following as important: Education, eugenics, inequality

This could be interesting, too:

Jeremy Smith writes UK workers’ pay over 6 years – just about keeping up with inflation (but one sector does much better…)

Joel Eissenberg writes The Trump/Vance Administration seeks academic mediocrity

Bill Haskell writes Study Shows Workers Fleeing States With Abortion Bans

Angry Bear writes The Impact of Debt Interest Payments

Eugenics has a bad reputation. Even the word "eugenics" is repugnant to many people, associated as it is with atrocities - forced sterilization programmes in America, for example, and of course the horrors of Nazi Germany. We like to see eugenics as discredited pseudo-science that has been consigned to the dust of history. Never again will we treat people as expendable simply because of their inherited characteristics.

But ideas that we discard because of their horrible consequences have a way of returning, dressed up in respectable clothing. Eugenic ideas have existed - and been acted upon - since ancient times. The idea of eliminating those who are, or will be, a burden on society because of disability raises hackles now, but in ancient Rome it was regarded as a public duty. The Biblical ban on marriage between close relatives effectively prevented birth defects due to consanguineity - but among the Pharaoahs of ancient Egypt, marriage between very close relatives was common, possibly to preserve the bloodline. The young Pharaoah Tutankhamen's health was compromised by his incestuous origin. We don't think of restricting or encouraging marriage between relatives as eugenics, but that's what it is.

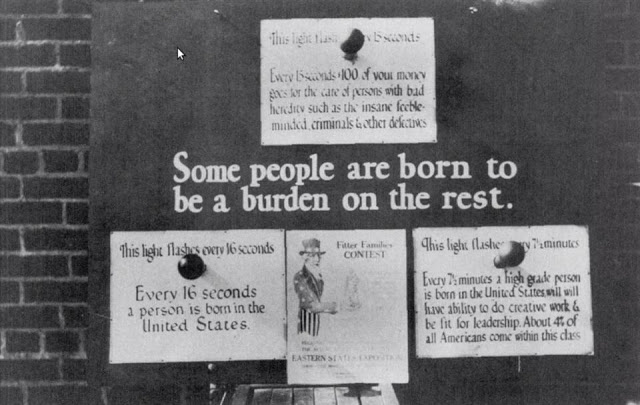

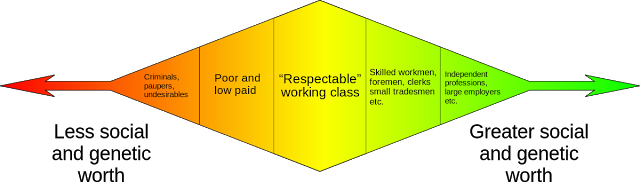

19th century eugenicists such as Francis Galton distinguished between "positive" and "negative" eugenics. Convinced that intellect as well as physical characteristics were inherited, and that income and social position were absolutely indicative of intelligence (or its absence), Galton thought that selective breeding could raise the general intelligence level of the population and avoid what he called "regression to the mean" - the tendency of children of highly intelligent people to be less intelligent than their parents. He thought that positive eugenics (encouraging those with desirable characteristics to intermarry) should apply to the upper classes, while negative eugenics (discouraging or preventing breeding) should be applied to "criminals, paupers and undesirables":

We might now object to such blatant association of class with intelligence - though as we shall see, some people still think such an association exists. But even if we buried eugenics at the cross-roads with a stake through its heart, it would still rise again in another form. Everyone wants to improve society, after all.

Furthermore, as Alvin Roth has shown, repugnance can inhibit beneficial developments. As eugenics rises from the ashes once again, therefore, we need to conquer our distaste, and examine it, unflinchingly and with clear sight, to determine what relationship if any its new forms bear to the horrors of the old, and whether they would deliver the good that their proponents claim.

On this basis, I made myself read Toby Young's essay about meritocracy in the Australian online magazine Quadrant, and the shorter article in the Spectator in which he lays out his scheme for the poor to have what he calls "designer babies". I have taken a pdf copy of the Quadrant essay, which you can download here.

Toby Young's view of "merit" is fundamental to his concept of "progressive eugenics", and also fundamentally at odds with his father's view. In his book The Rise of the Meritocracy, 1870–2023: An Essay on Education and Equality, Young's father, the socialist peer Michael Young, foresaw a dystopian future, which he termed "meritocracy". Here is how Toby Young describes his father's thinking (my emphasis):

In spite of being semi-fictional, the book is clearly intended to be prophetic—or, rather, a warning. Like George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four(1949), The Rise of the Meritocracy is a dystopian satire that identifies various aspects of the contemporary world and describes a future they might lead to if left unchallenged. Michael was particularly concerned about the introduction of the 11+ by Britain’s wartime coalition government in 1944, an intelligence test that was used to determine which children should go to grammar schools (the top 15 per cent) and which to secondary moderns and technical schools (the remaining 85 per cent). It wasn’t just the sorting of children into sheep and goats at the age of eleven that my father objected to. As a socialist, he disapproved of equality of opportunity on the grounds that it gave the appearance of fairness to the massive inequalities created by capitalism. He feared that the meritocratic principle would help to legitimise the pyramid-like structure of British society.Now, there is a blatant, and I suspect deliberate, error here. Michael Young did not oppose equality of opportunity. He objected to the inequality of opportunity that the grammar school system created. A privileged few - selected at an early age - would have excellent education, leading to advantages in employment, income and wealth that would be theirs for life and could be passed on to their children in a variety of ways. The remainder would be permanently denied this opportunity. Michael Young was absolutely correct that the grammar school system reinforced the structure of British society. What he did not appreciate was that because it promised social mobility for intelligent children, and everyone wants to believe that their children are intelligent, it would be popular.

I live in an area which has grammar schools. House prices close to grammar schools are higher than anywhere else, because even though they are selective they are oversubscribed and therefore give preference to children who live close by. People who care about their children's education pay for coaching to get their kids through the 11 plus, if they can afford it, and sometimes even if they can't. I paid for coaching to get my son into a grammar school because the alternative was sending him to the worst school in England. Blame me if you will, but the welfare of my son was my primary concern, as it would be for any responsible parent.

When we visited Temple School, it was all too evident that it had suffered decades of neglect. The school buildings were crumbling, the school was pitifully short of resources, staff turnover was shockingly high and the children's behaviour was appalling. The boys' grammar school was the polar opposite - well-resourced, well-staffed, well-disciplined, and delivering excellent results. But both were state schools. Because the grammar school was popular with parents and delivered better exam results, attention (and money) was disproportionately given to it to the detriment of the high school. The boys that went to Temple School were thrown on the scrap heap at the age of 11. I don't know what happened to them. I am just thankful that my son was not one of them.

There is no doubt whatsoever that grammar schools are socially divisive and reinforce income and wealth inequality. I am a product of a grammar school myself, and I sent my son to a grammar school. But I would abolish them tomorrow, if I could.

My stance on grammar schools clearly sets me at odds with Toby Young right from the start. But I said I would examine his views unflinchingly and with clear sight.

In fact, Toby Young's observation that the term "meritocracy" has lost its original pejorative meaning and is now regarded as a "good thing" is an important insight. The debate is no longer about whether we should discriminate in favour of intelligent children, but how to discriminate:

The debate about grammar schools rumbles on in Britain, but their opponents no longer argue that a society in which status is determined by merit is undesirable. Rather, they embrace this principle and claim that a universal comprehensive system will lead to higher levels of social mobility than a system that allows some schools to “cream skim” the most intelligent children at the age of eleven.Remembering those poor boys at Temple School, I find this hijacking of the educational debate by the meritocrats despicable. Surely all children, regardless of their intellectual level, deserve the very best education we can provide?

But Young is a big advocate of discriminating in favour of highly intelligent children:

There is a consensus among most participants in the debate about education reform that the ideal schools are those that manage to eliminate the attainment gap between the children of the rich and the poor. That is, an education system in which children’s exam results don’t vary according to the neighbourhood they’ve grown up in, the income or education of their parents, or the number of books in the family home. Interestingly, there is a reluctance on the part of many liberal educationalists to accept the corollary of this, which is that attainment in these ideal schools would correspond much more strongly with children’s natural abilities. This is partly because it doesn’t sit well with their egalitarian instincts and partly because they reject the idea that intelligence has a genetic basis. But I’m less troubled by this. I want the clever, hard-working children of those in the bottom half of income distribution to move up, and the less able children of those in the top half to move down.At least Young has the honesty to admit that he doesn't give a stuff about less intelligent children. But Young's lack of interest in raising general educational standards raises an important economic question. Why does he think concentrating resources on the very intelligent is more beneficial to society than raising the general educational level? This statement simply begs the question:

Putting aside the issue about whether a meritocratic society is any fairer than the one we live in at present—or fairer than an aristocratic society—it’s hard to argue that it isn’t more efficient. All things being equal, a country’s economy will grow faster, its public services will be run better, its politicians will make smarter decisions, diseases are more likely to be eradicated, if the people at the top possess the most cognitive ability.It is by no means clear that this is the case. Improving the general educational level of the population improves productivity, which boosts GDP and raises living standards for all. And it benefits the very intelligent as much if not more than those of lower IQ, since intelligent people are often better able to take advantage of generally improved educational resources. Providing an excellent education for a privileged few - whether selected on class, wealth or intellect - and a much worse one for the rest is economically wasteful.

Even more importantly, Young's exclusive focus on the intelligent is ethically questionable. If intelligence is largely inherited, as Young believes (I am not going to argue about this here), why should discriminating against someone on the grounds of their IQ be more acceptable than discriminating against them on the grounds of other inherited characteristics, such as colour, gender, disability? Why should intelligence be the single factor that defines the value of an individual to society?

And this brings me neatly to Young's "progressive eugenics". Having decided that intelligence is inherited, and that only intelligent children deserve an excellent education, he then struggles with the inevitable result - a rigidly structured society in which the highly intelligent marry each other and produce intelligent children who benefit from the excellent education their intelligence demands and, in turn, marry each other and produce more intelligent children. Meanwhile, at the other end of the social pyramid, the underclass perpetuates itself - dim people marrying (or not) other dim people and producing dim children. Genetics being what it is, of course, from time to time two dim people will produce a genius, and two intelligent people will produce a dimwit. But the chances of this become smaller and smaller the more rigidly stratified society becomes and the more assortative mating becomes the norm.

Young recognises the essential unfairness of linking socio-economic status with IQ, and the possibility of such a rigidly structured society becoming unstable, though he fails to see that separating out intelligent children for special treatment makes the rigidity and unfairness worse. He does, however, suggest that the risk of instability would justify more redistributive taxation, and briefly considers a basic income to level the economic playing field for the poor to some extent.

But then he dismisses all such fiscal measures in favour of something entirely different:

I’m more interested in the potential of a technology that hasn’t been invented yet: genetically engineered intelligence. As with so many of the ideas explored in this article, this crops up in my father’s book, where it takes the form of “controlled mutations in the genetic constitution of the unborn … induced by radiation so as to raise the level of intelligence”. This technology is still in its infancy in 2033, with successful experiments only carried out on “the lower animals”, but another version of it may be available sooner in the real world—within the next five or ten years, if the scientists are to be believed.

I’m thinking in particular of the work being done by Stephen Hsu, Vice-President for Research and Professor of Theoretical Physics at Michigan State University. He is a founder of BGI’s Cognitive Genomics Lab. BGI, China’s top bio-tech institute, is working to discover the genetic basis for IQ. Hsu and his collaborators are studying the genomes of thousands of highly intelligent people in pursuit of some of the perhaps 10,000 genetic variants affecting IQ. Hsu believes that within ten years machine learning applied to large genomic datasets will make it possible for parents to screen embryos in vitro and select the most intelligent one to implant. Geoffrey Miller, an evolutionary psychologist at New York University, describes how the process would work:

"Any given couple could potentially have several eggs fertilized in the lab with the dad’s sperm and the mom’s eggs. Then you can test multiple embryos and analyze which one’s going to be the smartest. That kid would belong to that couple as if they had it naturally, but it would be the smartest a couple would be able to produce if they had 100 kids. It’s not genetic engineering or adding new genes, it’s the genes that couples already have."On the face of it, this doesn't look like a bad idea. After all, this is technology that the rich would have access to. Why not make it available to the poor as well, so that they can choose to have more intelligent children?

There is an obvious ethical problem with screening for intelligence. We already screen for disability to some extent, of course. This in itself raises ethical questions which I won't address here. But screening for intelligence brings us back to my earlier question about the ethics of discriminating between people on the grounds of intelligence, or rather potential intelligence (since although Young thinks intelligence is mainly inherited, he admits there is a substantial "nurture" component to realised intelligence in adulthood). Is it right to regard people of lower intelligence as inferior to those of higher intelligence? Is it right to deny them the right to life on that basis alone?

Selecting on grounds of intelligence would be a form of "positive eugenics", in that it would increase the general intelligence level of the population. But if it were merely a free choice by parents, I doubt if it would reduce intellectual inequality. Indeed, it could increase it, even if selection were free for the poor. The vast majority of children are conceived naturally, so would not go through in vitro selection. I hate to say this, but the potential parents who would opt for selection are likely to be more intelligent anyway: their aim would be to avoid having a child who is not intelligent enough to qualify for selective education. Those who have never benefited from selective education themselves might not want their children to be more intelligent than them, or they simply might not care about their children's intellectual level. We know that one of the biggest obstacles for intelligent children from disadvantaged backgrounds is the attitude of their family and peers to education: "grammar schools are for toffs", "university is not for people like us", "you must leave school and get a job as soon as you can to bring money into the household". Why would parents who currently can't be bothered to put their clever children through the 11 plus, encourage their studies at home or support them through university, be remotely interested in going through IVF purely to ensure that they have clever children? Sorry, Toby, but it just doesn't stack up.

But Young has bigger ambitions for this programme than simply raising the general intellectual level of the population (my emphasis):

Hsu’s solution is to make it freely available to everyone, but that would only help to prevent it making existing inequalities even worse. After all, if people from all classes used it in exactly the same proportions, all you’d succeed in doing would be to increase the average IQ of each class, thereby preserving the gap between them. Wouldn’t it be better to limit its use to disadvantaged parents with low IQs? That way, it could be used as a tool to reduce inequality.

This technology might actually be more effective than anything else we’ve tried when it comes to tackling the issue of entrenched poverty, with the same old problems—teenage pregnancy, criminality, drug abuse, ill health—being passed down from one generation to the next like so many poisonous heirlooms. In due course, why not conduct a trial in a city like Detroit and see if it works? It has become a cliché to point out that the disadvantages of being brought up in a low-income family are apparent when a child is as young as eighteen months, so it shouldn’t take long to see if increasing the IQs of children from deprived backgrounds makes an impact. It would be inexpensive, too, so wouldn’t involve a massive hike in taxation. “The cost of these procedures would be less than tuition at many private kindergartens,” says Hsu.IVF and genetic screening as a form of social engineering. My initial instinct is repugnance - this is far too close to the racist eugenics of Nazi Germany for my liking. But I must put aside my distaste and examine this idea, too, unflinchingly and with clear sight.

Given what I said before about social attitudes, this would have to be a coercive programme. Potential parents would not only have to be offered free IVF and genetic selection, they would have to want to accept it. There would have to be some kind of strong incentive, probably in the form of money. This could be of the carrot variety ("if you opt for this we will pay you £500"), or the stick variety ("only children conceived through IVF and genetic screening will qualify for child benefit"). We don't know which Young would prefer, but government policy towards the "undesirables" over the last few years has definitely been of the "stick" variety. It would not be hard to devise sanctions programmes for parents who opted for natural conception instead of IVF and screening. *

But what if, despite all the carrots and sticks, the "undesirables" still produced significant numbers of naturally-conceived children who, we presume, would be of lower intelligence? For example, I am struggling to see how this "voluntary" IVF programme, even with incentives, would attract teenage girls. If they cared enough to go through an invasive IVF and genetic screening programme, they would care enough to use effective contraception so as not to get pregnant in the first place. Again, this founders on Young's assumption that the modern-day equivalent of Galton's "undesirables" would be motivated enough - and personally organised enough - to take advantage of his scheme. If they were, they wouldn't be in the underclass.

In fact it is possible that this scheme would simply result in more children being born to the "undesirables", rather than a rebalancing towards fewer children of higher intelligence as Young presumably intends. The IVF children, we assume, would rise up the social ladder. But that would still leave a substantial underclass of children conceived naturally. It is not hard to imagine what might happen next. Coercive abortion of naturally-conceived children, perhaps? Denial of healthcare and education to naturally-conceived children? Compulsory medication of naturally-conceived children to raise their IQ levels? Sterilisation of women who were eligible for IVF and genetic screening but opted to have a naturally-conceived child? I'm appalled. We should not even contemplate going down that path.

So what alternatives might there be? In his Spectator piece, Young suggested that the rich might somehow be prevented from screening for intelligence. How on earth this could be achieved is beyond me. The rich can always get what they want. The people who would be denied access to the scheme would not be the rich, they would be the socio-economic groups just above the "undesirables". They would be unable to afford screening without significant hardship, but would not be poor enough to qualify for free screening. I suppose, if the takeup were sufficient among the "undesirables", it would level the playing field somewhat among lower socio-economic groups. But it would be extremely unpopular. The "in-betweeners" are angry enough already that people only slightly poorer than them get benefits that they don't get. Just imagine how they would respond to a scheme designed to eliminate the one inherent advantage they think they have over the "undesirables", namely that they are brighter.

But even if the scheme worked, compositional effects would negate its effects anyway. Let's assume that the very poor do take up the offer of free IVF and genetic screening in sufficient numbers to make a significant different to the general intelligence level of their children. Let's further assume that the very rich also obtain screening, because they can. And let's make one more assumption, related to my earlier comment about parents who care about their children paying to coach them for the 11 plus. Let's assume that most parents pay for screening, even if they can barely afford it, because they want their children to be intelligent enough to qualify for the best education. The only people who don't have screening are those who are too poor to afford it but aren't the very poorest, and those who don't care about their children's intellectual level. What does this do to the structure of society?

Clearly, we have a new underclass. The "undesirables" eventually disappear as their children move up the social ladder. And their place is taken by those who didn't quite qualify for free screening but couldn't or wouldn't pay for it themselves. They become the new "undesirables". The general intelligence level in the population is a little higher, which could give a boost to GDP and living standards: but inequality, and social disadvantage for those at the bottom of the pile, are as high as ever. Young correctly points out that making the scheme generally available irrespective of means couldn't possibly reduce the intelligence difference between rich and poor. But neither could his limited scheme aimed at the poorest. There is no way this scheme could achieve the rebalancing he intends, unless it were extremely coercive and applied at all levels of society - in which case we would be back to the horrors of old.

And there is one further compositional problem. If the scheme succeeded in significantly narrowing the range of intellectual capacity in the population, it would be much harder to justify selecting the most intelligent for preferential education. Indeed it would be something of a kick in the teeth for those parents who did the "right thing" by opting for screening, and even paying for it themselves, only to find that the ensuing offspring still didn't qualify for better education. They would be damned angry - and with reason. To placate them, grammar schools would probably have to be abolished. Toby Young's scheme would force government to introduce the universal comprehensive system that he so detests.

I have no doubt that Toby Young devised this scheme with the best of intentions. But so did the eugenicists of the past. America's forced sterilization programmes were done "for the public good". Good intentions are no justification for a scheme that is ethically dubious, economically wasteful, and socially destructive. Toby Young's "progressive eugenics" is every bit as repugnant as the discredited eugenics of the early 20th Century.

Related reading:

Are there any limits to what schools can achieve? - Young

Hereditary talent - Francis Galton

The Armadillo Gauge - Adaptive Delivery

The New Ruling Class - Helen Andrews

* Thomas Malthus recommended restriction of welfare benefits for the poor to prevent them breeding back in the early 19th century, of course. There is nothing new under the sun.