In August 2014, I wrote this post arguing that harsh austerity during the Depression caused Hitler's rise to power. At the time, my argument seemed controversial, at least in Germany. There, it is not the austerity of 1930-32 that is blamed, but the debt-driven hyperinflation of a decade earlier. Germans remain terrified of both inflation and debt to this day.I am certainly not the only person to identify a causative link between austerity and Hitler. Here is Paul Krugman slapping down Eduardo Porter in 2015, for example: Yes, there was a hyperinflation in 1923, which may have helped radicalize German politics. But the proximate factor in Hitler's rise to power was the great deflation of the 1930s, brought on by a disastrous attempt to stay on gold. Disastrously staying on gold might

Topics:

Frances Coppola considers the following as important: austerity, fiscal policy, Germany, history, Monetary Policy, politics

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Skidelsky writes Lord Skidelsky to ask His Majesty’s Government what is their policy with regard to the Ukraine war following the new policy of the government of the United States of America.

Joel Eissenberg writes No Invading Allies Act

Ken Melvin writes A Developed Taste

Bill Haskell writes The North American Automobile Industry Waits for Trump and the Gov. to Act

In August 2014, I wrote this post arguing that harsh austerity during the Depression caused Hitler's rise to power. At the time, my argument seemed controversial, at least in Germany. There, it is not the austerity of 1930-32 that is blamed, but the debt-driven hyperinflation of a decade earlier. Germans remain terrified of both inflation and debt to this day.

I am certainly not the only person to identify a causative link between austerity and Hitler. Here is Paul Krugman slapping down Eduardo Porter in 2015, for example:

Yes, there was a hyperinflation in 1923, which may have helped radicalize German politics. But the proximate factor in Hitler's rise to power was the great deflation of the 1930s, brought on by a disastrous attempt to stay on gold.Disastrously staying on gold might of course have been due to the recent experience of hyperinflation. In 2014, when Bulgaria was unable to pay insured depositors for six months after a bank failure, the central bank refused to relax the Euro peg so that the necessary money could be created. When I asked why, my Bulgarian friends reminded me that Bulgaria had suffered hyperinflation in 1996. "If the central bank printed money, there would be riots in the streets," they said. The scars of hyperinflation can take a very long time to heal.

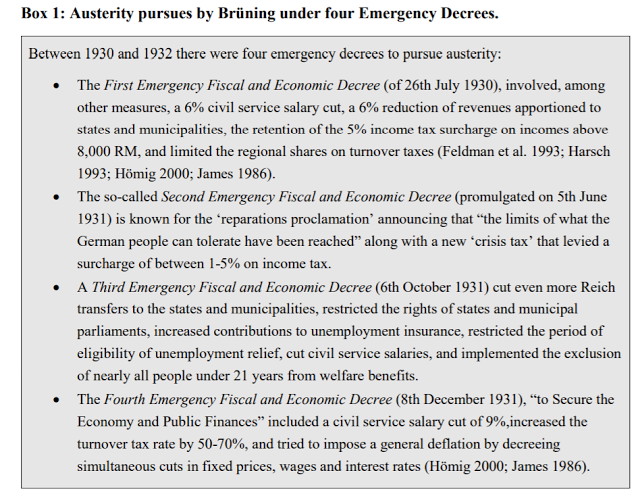

But Chancellor Brüning's austerity policies went far beyond keeping interest rates high to stay on the gold standard and stem capital flight. A series of draconian fiscal budgets imposed severe spending cuts and tax rises:

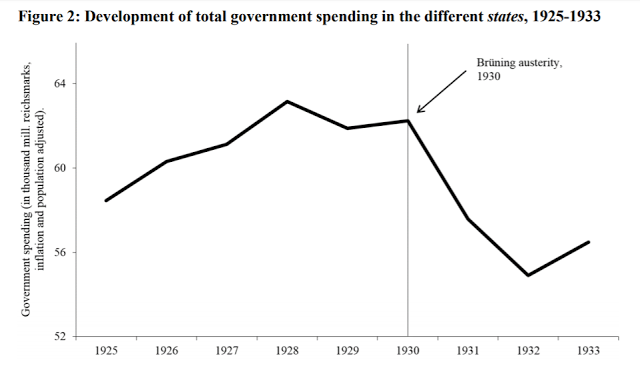

The degree of fiscal consolidation achieved by these decrees, and the speed of the adjustment, was remarkable: But there was an ulterior motive for this harsh austerity programme. Embedded in the "Second Emergency Fiscal and Economic Decree" of 5th June 1931 is a "reparations proclamation" that announced that "the limits of what the German people can tolerate have been reached". Brüning, it seems, wanted to engender desperate hardship among the German population in order to persuade the Allied powers to cancel the WWI reparations. And he succeeded. The reparations were suspended in 1931 and cancelled in the Lausanne conference of June-July 1932. Hitler became Chancellor in January 1933. Contrary to popular opinion, therefore, neither the 1923 hyperinflation nor the WWI reparations were the direct cause of Hitler's rise to power.

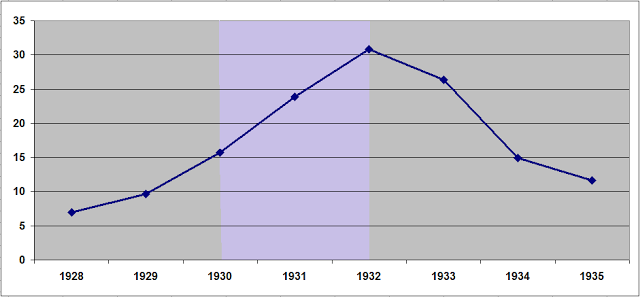

So what was? Well, unemployment was shockingly high, touching 30% in 1932:

chart from Willi Albers, 'Handwörterbuch der Wirtschaftswissenschaft, Band 9, 1982, ISBN 3-525-10260-7, p. 85, CC BY 1.0, via Wikipedia

Maybe the German people, sick of unemployment and poverty, voted for Hitler because he promised relief from austerity?

According to a new research paper (pdf, gated) that's exactly what happened:

With dashed hopes and a loss of faith in the Weimar Republic, fury and despair were channelled into the ranks of populists and demagogues, with the Nazi party campaigning against austerity and offering promises for a new era of prosperity.But wait. It wasn't the poor and the unemployed who voted for Hitler:

In fact, much of the growth in support for the Nazi party came from the middle classes, who were fearful of the Communists. The Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands (KPD) had achieved 16.9% of the vote by November 1932 (about 100 seats out of 584 in the Reichstag). The Nazis also received support from elites. During the 1920s, those with the highest incomes lost income more quickly than those at the bottom (Adena et al. 2015; Piketty 2014; Satyanath et al. 2017; Schreiner 1932). It was not that Hitler did not try to appeal to the unemployed masses, but rather that the Communist Party was perceived as the party that traditionally represented workers’ interests. Ultimately, Hitler’s attempts to attract the unemployed were ineffective (King et al. 2008; Petzina 1977).The Nazis were a party of the middle and upper classes.

This was a surprise to me. I thought that unemployment was the principal reason why people turned to the Nazis. But the researchers found that unemployment growth was negatively correlated with support for the Nazis. In other words, Nazi support grew when unemployment was falling.

It seems that the real driver was the sharp fiscal consolidation imposed by Chancellor Brüning. Draconian spending cuts, tax rises and deliberately deflationary policies in a severely depressed economy had dramatic political effects (my emphasis):

We find that austerity measures are correlated with the rise of the Nazi party in interwar Germany, offering econometric support for the argument that austerity created polarization and radicalisation of the German electorate. Each 1 standard deviation increase in fiscal consolidation was associated with between 2 and 5 percentage point increase in votes to the Nazis or up to one quarter or one half of one standard deviation of the dependent variable.Yes, I know - correlation isn't causation, and all that. But it clearly isn't possible for causation to be the other way round, and although there could be other drivers, the hurt caused by austerity is a rational explanation for rising Nazi votes. "Austerity caused the rise of Hitler" is a reasonable working hypothesis.

But we know that fiscal consolidation tends to affect the poor the most. So why did it cause better-off Germans to vote for extremists?

Better-off they may have been, compared to the poor and the unemployed, but they didn't see it that way. They resented government policies that cut their wages, raised their taxes and reduced their pensions and benefits when they were already suffering because of the economic depression. And they also resented those who were poorer than them, because the really poor received some government support, while they got nothing:

.....austerity measures contributed to votes for the Nazi party among middle- and upper-classes who, despite the depth of the Depression (i.e., after controlling for the level of output and employment) still had something to lose and may have resented government austerity in the face of Depression (a pocket book motive) and while other segments of society received benefits from relief or automatic stabilizers.They were what Theresa May dubbed the "Just About Managing", and I have called the "in-betweeners". They bore the full brunt of tax rises, spending cuts, the deliberate wage-price deflation imposed by Brüning, the extremely tight monetary policy needed to maintain the gold standard and the effects of the Depression itself. They weren't wealthy enough to weather the storm unscathed, but they were too well-off to receive any support. And the public services on which they relied were being cut to the bone. They saw no future for themselves or those they loved. They became angry and desperate - and desperate people are cannon fodder for extremists.

Perceptive as ever, John Maynard Keynes warned in 1932 (emphasis in original):

....many people in Germany have nothing to look forward to – nothing except a ‘change’, something wholly vague and wholly undefined, but a change.Now where have we heard something very like this recently?

The Nazi party certainly offered a change. It campaigned on an anti-austerity manifesto, promising generous pensions, infrastructure investment (notably roads) and restoration of welfare benefits. The Communist party had a similar manifesto, of course, but the German middle classes were frightened of the Communists. So they fled to the Nazis in droves. By the time Brüning was replaced with a less austerity-minded Von Papen in 1932, it was already too late to save the Weimar republic - and the lives of 60 million people.

Of course, the researchers warn that there may also be other reasons why better-off Germans turned to the Nazis, including anti-semitism. Humans are complex creatures: there is seldom one single reason for the rise of a populist movement. But the terrible folly of imposing austerity in a deeply depressed economy seems clear.

And therein lies the warning for today. Austerity policies in a depressed economy cause political crisis:

....even when the particular history of a country precludes a populist extreme-right option, austerity policies are likely to produce an intense rejection of the established political parties, with the subsequent dramatic alteration of the political order.In the UK, years of foolish, harmful and wholly unnecessary austerity policies - about which I and many others repeatedly warned - have already plunged the country into deep political crisis. Brexit is no accident: a straight line can be traced from the financial crisis, through the years of stagnation and austerity, to the rise of UKIP and ultimately to the Brexit vote. A deep fault line has opened up, fracturing the political system and undermining the UK's system of representative parliamentary democracy.Today's politics is driven not by Left versus Right, but by Leave versus Remain, or as David Goodhart would have it, the "somewheres" versus the "anywheres". And the damage to the social fabric of the UK is already evident. Families are split, friends lost, relationships broken. Where will this end? I do not know.

The US, too, is in political crisis. There, the fracture is more external than internal. The world's hegemon is threatening to abandon globalisation and adopt 1930s-style protectionist trade practices. The consequences for world trade, and indeed for world peace, could be serious indeed.

The EU has yet to suffer its political crisis. But it will come. The researchers observe that the EU appears to be repeating the mistakes of the 1930s. And they warn:

The case of Weimar Germany explored in this article provides a timely example that imposing much austerity and too many punitive conditions can not only be self-defeating, but can also unleash a series of unintended political consequences, with truly unpredictable and potentially tragic results.Learn from your history, Europe, before it is too late. Unless there is radical loosening of the fiscal straitjacket into which too many countries have been tied, your political crisis, when it comes, will be terrible indeed.

Related reading:

The Worst Political Storm In Years

Austerity and the rise of populism

Anti-nationalism

When the world turns dark

What have we learned from history?

Study: austerity helped the Nazis to come to power - Vox

The chilling irony of German austerity - The Week

Image is from The Week.