This post originally appeared on Pieria in July 2014. Roger Farmer has a blogpost in which he shows that labour markets don’t clear. Specifically, employment varies with the business cycle, whereas the labour force participation rate and hours worked only show long-term secular trends. During cyclical downturns, therefore, we must conclude that there is more labour available than there are jobs. New Keynesians say that the reason for this is sticky wages. If only nominal wages could fall enough,the market would clear and there would be no cyclical increase in unemployment. Therefore there should be labour market deregulation so that wages can flex with the business cycle. Roger Farmer questions this: he argues that the market simply does not clear at any wage. I disagree. I think the

Topics:

Frances Coppola considers the following as important: labour, Pieria, wages, welfare, work

This could be interesting, too:

Jim Stanford writes Interrogating the ‘Vibecession’

Merijn T. Knibbe writes The political economy of estimating productivity.

Sandwichman writes Alienated labour and disposable time

Angry Bear writes Wage Growth Is Declining Across Sectors, but Not at the Same Rate

This post originally appeared on Pieria in July 2014.

Roger Farmer has a blogpost in which he shows that labour markets don’t clear. Specifically, employment varies with the business cycle, whereas the labour force participation rate and hours worked only show long-term secular trends. During cyclical downturns, therefore, we must conclude that there is more labour available than there are jobs.

New Keynesians say that the reason for this is sticky wages. If only nominal wages could fall enough,the market would clear and there would be no cyclical increase in unemployment. Therefore there should be labour market deregulation so that wages can flex with the business cycle. Roger Farmer questions this: he argues that the market simply does not clear at any wage.

I disagree. I think the market does clear – when wages fall to starvation level. Humans need a minimum income to sustain life, but employers have no responsibility for ensuring that the remuneration of employees meets that minimum subsistence level. Therefore, in an economic downturn, the market-clearing price of labour can fall to below the minimum needed to sustain life. When wages are at starvation level, hours worked, labour force participation rate and workforce size all decline as people become weak, ill and eventually die – or, if they can, leave for somewhere more prosperous. Reducing the size of the workforce means that the market will eventually clear and wages start to rise again – for those who have survived.

This is the fundamental flaw in the “sticky wages” argument. In an economic downturn, the labour market cannot clear without incurring unacceptable social costs. Malnutrition, starvation, disease and death are the consequences of freely falling wages in an economic downturn. The reason why labour markets don’t clear is that we don’t want them to. Of course, if for some reason we think allowing people to starve to death (or emigrate) is acceptable, then the labour market will eventually clear - as it did in 19th-century Ireland. It cost the lives of an estimated one million people.

It all starts with unemployment benefits. Because we don’t like people to starve in cyclical downturns, governments in developed countries have created financial safety nets for the unemployed. Now, extreme free-market aficionados criticise these for causing unemployment: they believe that if unemployment benefits were cut or eliminated, the unemployed would be forced to find work. And they have a point. When there are unemployment benefits, people will prefer unemployment to accepting work at below unemployment benefit level. Unemployment benefits therefore act as a wage floor, preventing wages from falling below subsistence level. The result is that the labour market fails to clear and we have stubborn unemployment.

Of course, this assumes that people can choose to receive unemployment benefits rather than accept work at very low wages. But this is unpopular with the working people whose taxes pay the unemployment benefits. Working people don’t like seeing the unemployed being (as they see it) paid not to work: it seems unfair that they should work hard for their money while others get “something for nothing”. Some governments respond to this by introducing some form of workfare, where people “earn” their unemployment benefits by doing some kind of community service or unpaid “work experience”. Others impose sanctions such as loss of benefits for refusing work. And others cut unemployment benefits in an attempt to “make work pay”. The effect of this is to reduce or remove the wage floor. Without other government intervention, sanctions and/or workfare cause wages to fall to the market-clearing price.

But

when wages fall below subsistence level there is pressure on government to top

them up: hard-working people really don’t like not earning enough to live on.

So the next stage of intervention is the introduction of in-work benefits to

support wages. These place further downwards pressure on wages, since employers

have an incentive to pay below subsistence level knowing that government will

top up wages, and employees will accept below-subsistence wages for the same

reason. When unemployment

benefits cannot act as a wage floor AND there are in-work benefits topping up

wages to subsistence level, the

market-clearing price of labour is zero or below (an unpaid internship with

no expenses is in effect a negative-wage job). This may be even lower

than the market-clearing price would have been without the combination of

in-work benefits with workfare or sanctions for the unemployed.

The tendency of wages to fall when there are in-work

benefits and unemployment benefits are stigmatized makes a minimum

wage necessary to prevent government becoming the de facto employer

of large parts of the workforce. But like any wage floor, this also prevents

the labour market clearing.

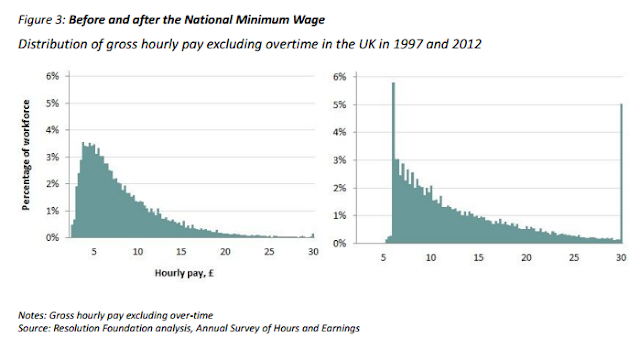

There is no doubt that a minimum wage distorts the labour market. These charts from the Resolution Foundation show the effect on the UK labour market of the minimum wage introduced in 1997:

(the spike at 30 on

the 2012 chart is not significant – it is caused by compressing the “tail” into

a single point to avoid having to extend the x axis).

There are two things to note here. First is the obvious spike at the minimum wage itself, which is much larger than we would expect from the truncation of the lower distribution. Second is the flattening of the curve. These two features are related. As the Resolution Foundation explains, the minimum wage has become the “going rate” in many sectors. It is acting as a wage ceiling as well as a wage floor. The Resolution Foundation’s report goes on to examine ways in which a surrogate wage distribution could be created to reduce or eliminate clustering at the minimum wage. Intervention in markets causes distortions which require more intervention…..In the medical profession they call this the “spiral of intervention”. The same thing happens in policymaking.

The spiral of intervention is not without costs. The Resolution Foundation’s second chart is unfortunately from 2012, which was during a period of poor economic performance for the UK. But it does suggest that the market-clearing price of labour is far below the minimum wage. I suspect that this is the case even in normal times – and it is because of the distorting effect of the UK’s combination of unemployment-benefits-with-sanctions and in-work benefits.

So wage subsidies in economic downturns are reasonable countercyclical policy, supporting people so that they can live even when the market-clearing price of labour has fallen way below subsistence level. But use of wage subsidies in normal times to support living standards because wages are persistently below socially acceptable levels is a different matter. It is systematic intervention in labour markets for political, social and moral reasons. And it raises serious questions about the nature of “private” enterprise. If labour costs in “private” enterprises have to be heavily subsidised in order to maintain an acceptable level of employment and living standards, can they really be said to be private?

Related reading:

A Very British Disease

Productivity and Employment: A Cautionary Tale

The changing nature of work

Bifurcation in the labour market

Economic equivalence: job guarantee and basic income

Image is of the Famine Memorial in Dublin.