Who decides what statistical offices measure and how they measure it? And what are the implicit values embedded in these decisions? Recently, the ILO issued a new manual on measuring productivity. Below, I´ll discuss the questions posed. But for starters, it is essential to realize that economists measure monetary productivity, not physical productivity, which leads to problems with ever-changing prices. This will be part of the discussion. The ILO (International Labour Organization) is the only tripartite international organization (governments, labour, and employers). One of its tasks is to assemble statistics on labour and organize the global discussion about the concepts of ´unemployment´ and ´labour´. To give an idea, they assemble statistics on paid labour, forced labour,

Topics:

Merijn T. Knibbe considers the following as important: business, Economics, economy, ILO, labour, news, politics, prices, productivity, Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Schuldenbremse bye bye

Robert Skidelsky writes Lord Skidelsky to ask His Majesty’s Government what is their policy with regard to the Ukraine war following the new policy of the government of the United States of America.

Lars Pålsson Syll writes What’s wrong with economics — a primer

Who decides what statistical offices measure and how they measure it? And what are the implicit values embedded in these decisions? Recently, the ILO issued a new manual on measuring productivity. Below, I´ll discuss the questions posed. But for starters, it is essential to realize that economists measure monetary productivity, not physical productivity, which leads to problems with ever-changing prices. This will be part of the discussion.

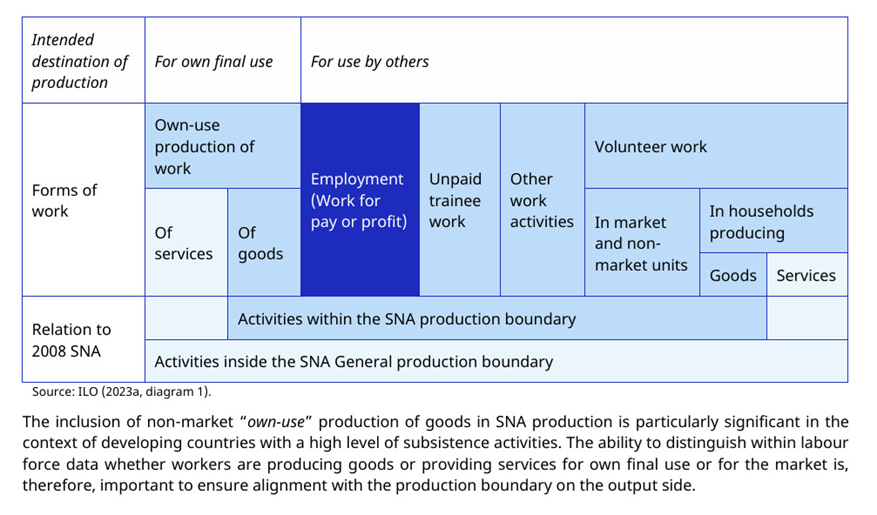

- The ILO (International Labour Organization) is the only tripartite international organization (governments, labour, and employers). One of its tasks is to assemble statistics on labour and organize the global discussion about the concepts of ´unemployment´ and ´labour´. To give an idea, they assemble statistics on paid labour, forced labour, migratory labour, household labour and much more. Their basic framework for doing this is the same framework used for the national accounts (Diagram 1). The upside of this is that it means we have a set of consistent production and labour statistics. The downside: activities outside the national accounts production boundary (light blue in the diagram) are less well measured. This boundary is also used to measure productivity, or ´unit of output per unit of input´. Washing machines increased physical production and productivity in households (but also in the national accounts sector). This increase is not included in productivity statistics. Addendum: part of household production, especially in agriculture, is included in the national accounts production boundary. The most essential household ´activity´ included is the ´production´ of imputed rents of owner-occupied dwellings. Do not underestimate this.

Diagram 1. The production boundary used to measure production and the use of labour (including unemployment) and productivity.

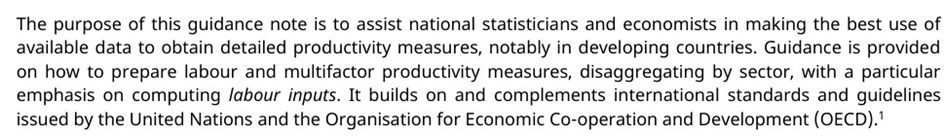

- It seems logical that the ILO is included in the processes that lead to conceptualising and defining variables like unemployment. But why is it bothered by productivity? Labour input (hours, jobs, persons,…) is an important element of productivity estimates. In their words, in the recent manual:

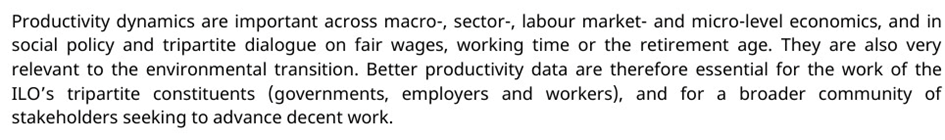

- International organizations are intimately involved with conceptualizations and definitions (just like national statistical offices). As these organizations are interested in productivity, it is logical to include the ILO in the process. But is there a more profound reason to focus on the concept and definition of productivity)? Yes. From the manual:

To focus on labour: the ILO emphasizes positive feedback between increases of productivity and the quality and remuneration of jobs (but read between the lines!):

- There are, however, problems. For instance, ´QALI´ is increasingly used to estimate labour input (Quality Adjusted Labour Input). But what is quality? For one thing, people’s productivity depends on the situation. According to the ILO, Quality adjustments have to be adjusted to include self-employment, informality, skills mismatches and the gender wage gap (if a man and a woman do the same job with the same physical output and the woman gets lower wages but productivity is measured by estimating wages…).

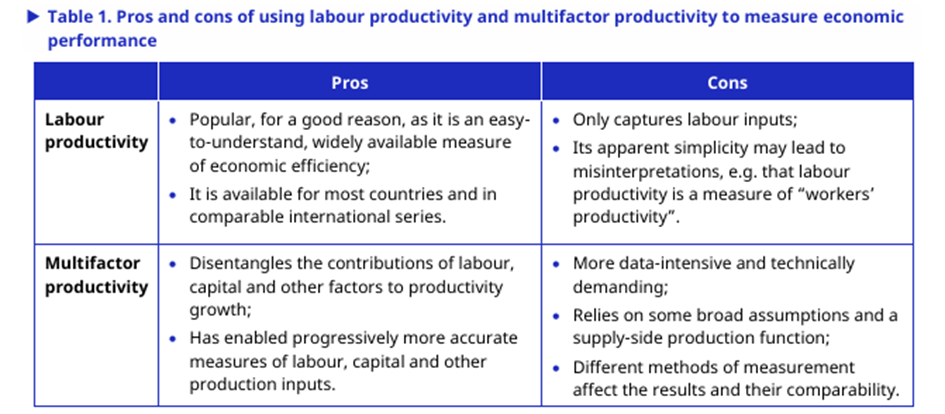

- Some other problems: multi-factor productivity. It is possible to make reasonable estimates of production per hour, full-time job, or, in agriculture, per cow or hectare. But how do we combine such estimates? A farmer produces more per hour of labour input when using a combine harvester, but how do we establish an index of inputs that includes the harvester (and the energy it uses) and the farmer? That´s… a problem. According to a footnote in the report:

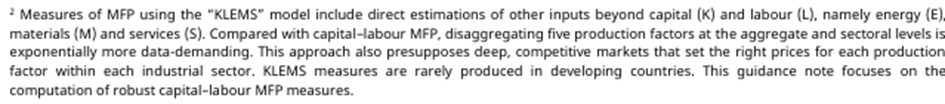

- The report provides an overview of the pros and cons of different approaches:

- Beyond the report: Capital. On one side, it´s impossible to make unbiased estimates of the value of capital and land as these values are influenced by ownership structures and, as fixed capital lasts multiple years, by complex interactions between changing interest rates, write-downs, technical obsolescence and the introduction of new technologies. On the other side, energy production is highly capital- and land intensive and requires limited amounts of labour – however, one measures ´capital´ and ´Land´, meaning it has high labour productivity, contrary to construction or the hospitality sector, which is clearly related to the abundant use of land (including natural resources) and produced fixed capital. When, like in the UK and the Netherlands, a country phases out the production of hydrocarbons, average productivity will fall even when one measurement might show a slightly larger or smaller fall than another.

- The report also mentions problems with estimating the productivity of government activities (including education and healthcare) and the informal sector. Personal note: few sectors can be as innovative as education. Teachers adapted to remote work in days or even hours during the lockdowns. And time and again, new electronic possibilities show up almost directly in the curriculum (until management learns about this). There are also problems with including, by definition, hard-to-measure informal activities (not the same as illegal and criminal activities, which are sometimes very measurable and are included in the production boundary). Mind: informal lodging activities, for instance, a kind of AirBnB, use a house as capital input and are, hence, highly capital intensive.

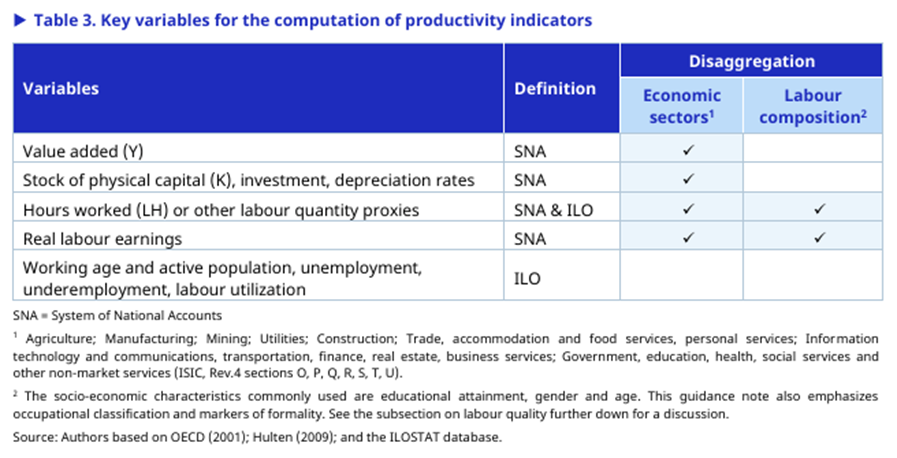

- The report makes a mistake in Table 3. As such it is an enlightening table. However, the national accounts distinguish between produced physical capital (houses, machinery, canals) and unproduced physical capital (hydrocarbons deep down in the ground). In the table, this distinction is obfuscated. But it does show that productivity, as economists measure it, is a monetary variable as value added is defined as the monetary value of outputs minus the monetary value of inputs. This means that ever-changing, relative and absolute prices are crucial to our productivity measurement. For an example: when the price of gold declines, while input prices stay the same, value added of mining gold can easily become negative. On a larger scale, this almost happened in the Irish construction sector around 2009. The losses caused by abandoned construction projects were absorbed by companies, banks and, ultimately, the Irish population. This leads to the question: how do we account for such events in our productivity statistics?

- The report contains highly useful overviews of different kinds of labour and different kinds of arithmetical productivity increases, like increases within a sector (replacing the sickle and flail with the combine harvester) and shifts between sectors (when a student working in the hospitality sector graduates and starts a job in the oil-producing business).

- The report does not delve into the complex subject of prices. As stated, economists measure monetary productivity, not physical productivity. Monetary productivity is measured by dividing value added by either a physical estimate of labour (or, increasingly, adjusted estimates of physical labour) or by an index of (price-weighted) non-labour inputs and labour. Value added is defined as the value of outputs minus the value of inputs. However, prices change. Economists do not want price increases to influence their measurement, so they calculate the value of inputs minus the value of outputs in constant prices. This, however, leads to two problems. Not all prices change in the same way. When prices of oil increase relative to other prices, the nominal value added in hydrocarbon extraction increases. As prices of oil increase more than other prices, this increase leads to a genuine increase of purchasing power of value added in this sector (and, as somebody pays these prices, to a decline in other sectors). Using fixed prices might give a reasonable estimate for the physical amount of output (the production side of value added). But it gives, in this case, a distorted idea of ´real income´in this sector. Looking at the input side, inputs are weighed with prices. When the price of energy used increases (or, in case energy is not included in our input estimates, the price of labour increases), the weight of this input in the mix of inputs increases. Fixed prices do not show this – unless the fixed prices are changed every years. Economists do use this procedure (changing fixed prices every year) but this forces them to construct a volume estimate of value added not by using the value of outputs and inputs in prices fixed for a longer period but by calculating changes of this volume using a different set of prices for the growth between, say, 2022 and 2023 and between 2023 and 2024.[1]

- Using growth rates in the way stated above hides, however, the real increase of purchasing power caused by higher oil prices or, to use another example, relatively high prices of drugs enabled by government patents. It is also clear that the purchasing power connected with increased oil prices flows largely to the owner of the natural resources, which may be a nation, a royal family or a company. On the other hand, increases in productivity, which are siphoned off by ever-lower product prices, might be good for consumers but not producers (which is, to quite an extent, what happened in European agriculture up to around 2022. The prices we use to estimate productivity also influence the distribution of the purchasing power of value added. On a related note, when wages increase, but machinery prices don´t, the weight of labour in the index used to calculate productivity will increase. When more machinery is used, but its weight in the index diminishes, it leads to a bias in estimating total factor productivity.

- Estimates of economic productivity are highly useful. But, as stated, many inputs are often excluded, while nominal prices are what is real to people consuming, investing, and producing. We should, hence, use inclusive estimates of productivity and enrich the analysis of ´real´ productivity with an analysis of nominal production and distribution.

- Returning to the questions: the ILO is one of the organizations influencing how economists measure productivity. They do add a highly welcome focus on different kinds of labour to the discussion. However, they also use what´s a neoclassical framework to the discussion by using only the production factors Capital (including Land) and Labour, which obfuscate the discussion as Land does not depreciate (and is hence easier to estimate than produced capital!) but also as ownership of Land and Natural Resources, like ownership of produced capital, does not only influence production and the use of labour but also the distribution of value-added and, hence, gains in productivity. As changes in relative prices influence the estimates and distribution, any analysis of productivity gains as estimated by economists should also delve into the influence of changing relative prices on production and productivity. To underscore this point, farm milk prices in the Netherlands did not increase between 1982 and 2019, while all other prices did. Farmers survived by increasing productivity – but consumers were the big winners.

[1] To my surprise, such estimates are not ´chaotic´ in the sense that relatively small changes in the prices used to lead, over time, to large and difficult-to-predict changes in the estimates of inputs and outputs. See Merijn Knibbe, ´Macroeconomic measurement versus macroeconomic theory´ (Routledge 2020) especially paragraph 8.3, ´putting formulas to the test: superlative index numbers and Dutch agricultural production and prices 1851-2016´.