Another day, another takedown of claims made by women's state pension age campaigners. This time, it's figures for benefit claims by women in their early 60s. David Hencke claims that sharp rises in the number of women in this age group claiming unfit-for-work benefits (ESA and legacy incapacity benefits) proves that losing their state pension entitlement is wrecking the health of women in this age group. And he argues that this calls into question the DWP's recent victory in the Court of Appeal:The disclosure of these figures -obviously not available at the time of the hearing – does undermine the forceful case made by Sir James Eadie, QC, who represented the Department of Work and Pensions, that any poverty or ill health suffered by these women could not be linked to the rise in the

Topics:

Frances Coppola considers the following as important: back to 60, pensions, WASPI

This could be interesting, too:

Nick Falvo writes Homelessness among older persons

Frances Coppola writes We need to talk about the state pension

Frances Coppola writes WASPI Campaign’s legal action is morally wrong

Frances Coppola writes Statistics for state pension age campaigners

Another day, another takedown of claims made by women's state pension age campaigners. This time, it's figures for benefit claims by women in their early 60s. David Hencke claims that sharp rises in the number of women in this age group claiming unfit-for-work benefits (ESA and legacy incapacity benefits) proves that losing their state pension entitlement is wrecking the health of women in this age group. And he argues that this calls into question the DWP's recent victory in the Court of Appeal:

The disclosure of these figures -obviously not available at the time of the hearing – does undermine the forceful case made by Sir James Eadie, QC, who represented the Department of Work and Pensions, that any poverty or ill health suffered by these women could not be linked to the rise in the pension age to 66.

Unfortunately, it doesn't.

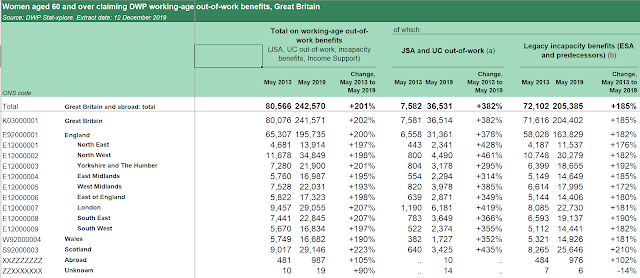

The figures released by the Commons Library on 18th September 2020 do indeed look damning. Here's an excerpt from their table, in which I have highlighted the headline figures:

As David correctly observes, when the state pension age was 60, women didn't claim unemployment benefit. So the 382% rise in JSA and out-of-work UC is the inevitable consequence of women aged between 60 and 65 losing their entitlement to state pension. If this table started from 2010 instead of 2013, the percentage rise for JSA and out-of-work Universal Credit would be even larger.

But when the state pension age for women was 60, women aged over 60 didn't claim ESA either, though they did claim other disability benefits. So the 185% rise in ESA is also the inevitable consequence of the rise in women's state pension age.

David claims that the 185% rise in ESA claims between 2013 and 2019 reflects actual worsening of women's health directly attributable to the loss of their state pensions. But there is no evidence for this in the Commons Library's figures. The rise is simply a matter of mathematics. It tells us absolutely nothing about the state of women's health.

Between April 2010 and November 2018, state pension age rose gradually from 60 to 65 for women born between 6th April 1950 and 5th November 1953. In 2013, the start point for this table, women's state pension age was between 61 and 62. So most women aged between 60 and 65 at that time were receiving a state pension, and therefore not eligible to claim JSA, ESA or out-of-work UC. But by 2019, women's state pension age had risen to 65 and was starting to rise towards 66. Every woman aged between 60 and 65 was eligible to claim those benefits. There was therefore a much larger number of women aged over 60 who could potentially claim ESA.

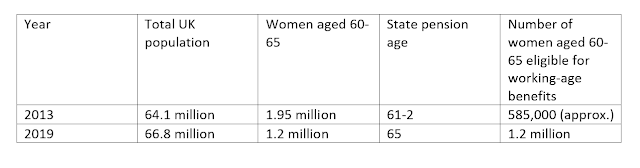

David assumes that the proportion of eligible women claiming ESA increased between 2013 and 2019. But the Commons Library figures don't actually say that. So, let's work some figures to see if his claim is reasonable.

The Commons Library says that the number of women claiming ESA and its precedessor incapacity benefits rose from 72,102 in 2013 to 204,202 in 2019. The DWP provides figures for the number of women aged 60-65 in each year.* Applying the state pension age in force for each year. gives the following estimates of women eligible for working-age benefits in the two years in question:

Two things spring out of this. Firstly, that the proportion of eligible women claiming unemployment benefit is very low, though it has more than doubled in the time. And secondly, that though there is a 5% rise in the proportion of eligible women claiming incapacity benefits, it is nowhere near the disaster that David Hencke claims. It is most likely accounted for by the fact that the average age of women aged 60-65 claiming ESA has risen, since the likelihood that someone has health problems severe enough to reduce or eliminate the capacity to work increases with age.

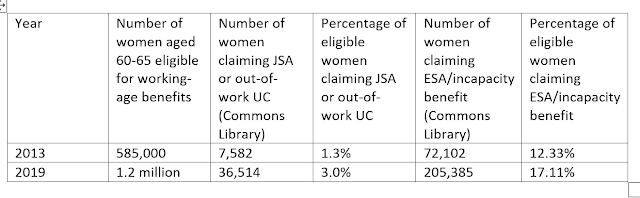

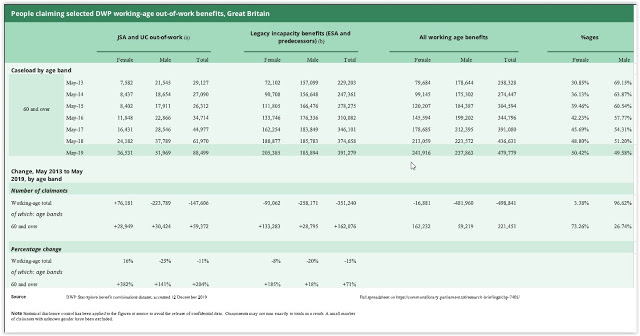

This table compares the rates of working-age benefit claims for men and women aged 60-65 between 2013 and 2019:

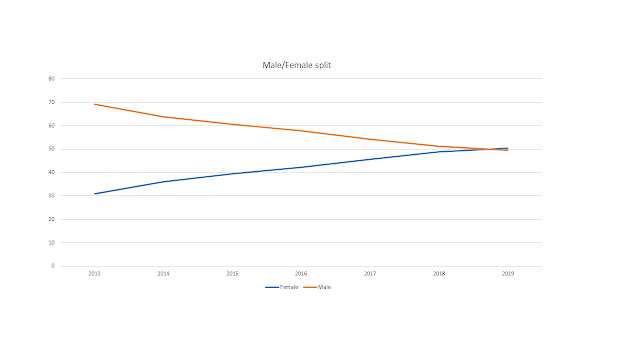

It's not the easiest table to read, so I have created three charts from it. First, here is the split of total working-age benefits between men and women. It's a percentage chart, so tells nothing about the number of claimants. What it shows us is that as women's state pension age has risen, the proportion of total working-age benefits claimed by women has risen and the proportion claimed by men has fallen. By 2019 the proportions had converged to approximately 50% each, exactly as we would expect from equalisation of state pension ages.

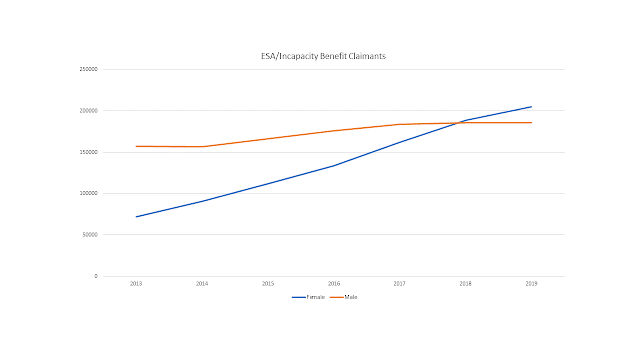

Next, ESA/incapacity benefit claims during the same period:

However, the fact that women's ESA claims now exceed those of men could suggest that the rise in state pension age has slightly worsened the health of women in this age group. But this is a dangerous assumption. The remarkable thing about this chart is not that women's claims have increased, it is that men's have not.

Men used to have the right to claim Pension Credit at women's state pension age. Unemployed men could, therefore, opt to claim Pension Credit instead of registering as unemployed. Similarly, if men were too ill or disabled to work, they could claim Pension Credit instead of incapacity benefits. And the NI autocredits scheme ensured that if they did claim Pension Credit (which does not include NI credits) they would still receive a full state pension when they reached 65. So, men who were already signed off work due to incapacity, and met means-testing criteria for Pension Credit, would disappear from the ESA statistics at women's state pension age just as women of their age did.

As women's state pension age rose, unemployed men progressively lost their right to claim Pension Credit and NI autocredits and were therefore forced to register as ESA/JSA/UC claimants. So we would expect male claims for ESA/incapacity benefits to have risen as women's state pension age rose. And they did, a bit, though they have plateaued since mid-2016. But they haven't risen anything like as much as ESA/incapacity benefit claims from women. Why?

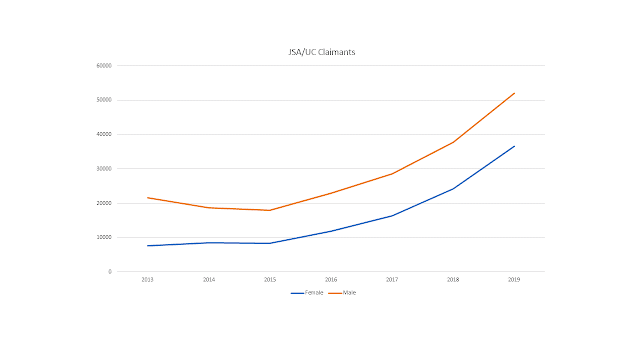

This chart is even more extraordinary:

It would be easy to explain this as men transferring from Pension Credit to unemployment benefits as women's state pension age rose. But this doesn't explain why men's unemployment claims remain considerably higher than women's. After all, with full equalisation, one would expect unemployment claims from both sexes to be equal.

One possibility is that unemployed women are less likely to register as unemployed because they are more likely to live with a partner who can support them. But this wouldn't explain why women's ESA claims now exceed those of men while men's JSA/UC claims continue to exceed those of women. After all, a woman who is unable to work due to illness and has a partner who can supporter might not claim ESA, either.

But there is another explanation which would cover both thhe disproportionately high unemployment claims from men and the disproportionately high ESA claims from women. That is social stigmatizing of men who are unable to work because of illness or disability.

There is a prevalent social belief among the 60-65 age group that men are "tougher" than women and therefore should be expected to work when a woman with an equivalent health condition would not. To what extent does this influence the benefit claims that people of this age group make? Is a woman with a health problem more likely than a man with a similar problem to claim ESA?

It's also possible that the discrepancy in the types of benefit claims made by men and women arises from systemic discrimination against men in the WCA process. Put bluntly, men are more likely than women to be judged fit for work. This might be because men tend to hide their fragilities, or it might be because the prevailing social belief in the toughness of men influences those conducting WCA assessments. It also might be that women are more likely to seek advice about the types of benefits they could claim, and more likely than men to be advised to claim sickness/incapacity benefits.

Whatever the reason, it appears that men aged 60-65 disproportionately claim unemployment benefits, while women disproportionately claim incapacity benefits. Whether this disproportion is reflected in actual discrepancy in fitness to work as objectively judged by medical professionals is at present unclear.

What is clear, though, is that David Hencke's claim that the rise in state pension age has caused a significant worsening of the health of women in the 60-65 age group is not supported by the Commons Library's figures. Although women seem to be more likely than men to be deemed unable to work, the difference could be explained by the social expectation that men will work even when ill - an expectation which probably contributes to their earlier deaths.

* The original version of this post estimated the number of women aged 60-65 in each year using a notional 5% of the UK population. Thanks to Michael O'Connnor for sending me the actual numbers as produced by the DWP.

Related reading:

Calculus for journalists

Probability for geeks

Arithmetic for Austrians

The true story of NI autocredits

The NI Fund's reserves don't pay down the National Debt

Dangerous assumptions and dodgy maths

Increases in the state pension age for women born in the 1950s - Commons Library

Second table courtesy of Suzy Allbright, based on the DWP's Gender and Age spreadsheet.

I have not provided a link to David Hencke's piece.